A decade ago only restaurant chefs knew about balsamic vinegar, and today the most mundane supermarkets stock several brands as well as a growing selection of balsamic vinegar salad dressings. You can buy it in bulk from some olive oil specialty stores, and every Italian restaurant worth it’s spaghetti offers an item or three made with balsamic. Chefs and foodies consider balsamic as essential as extra virgin olive oil. But the price for a bottle ranges from $5 to $500. How can that be? What is the difference?

Alas, there is not an easy answer, and if one goes to Modena, Italy, the small town where it was invented and where most of it is still made, answers are not much easier to find. Raise the question in a local wine bar and a fight might break out. And forget trying to learn about the subject on the internet. Inaccuracies are more common than facts on most websites.

That’s because, in an attempt to improve quality and build a bigger market, four competing trade associations and seven regulatory bodies have emerged. And they don’t get along. As a result, there are numerous labeling conventions, numerous methods of production, numerous claims of authenticity, and a boggling range of quality and price. This is all so odd in a country where so many food labels are so strictly regulated. Like cheese, wine, ham, olive oil, etc.

Bottomline

There are three primary grades of balsamico, and several subgrades: (1) Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale in two subgrades, extra vecchio and affinato; (2) Condimento Balsamico; and (3) Balsamic Vinegar di Modena (BVM) or “salad balsamic” as I call it. Most of the balsamic you see in groceries is salad balsamic, or BVM. Some of them are rated on a scale of 1 to 4 grape leaves, some of which have a red tag or a white tag, some of which have flavorings added, and some of which are concentrated into a glaze. Technically there is no such thing as white balsamic, at least not in Italy.

Nobody knows what balsamic vinegar really is because, although the Italian government has definitions, there are so many loopholes, and other countries, especially the US, feel free to abuse the name however they want. But if you sit down with a tall drink, or maybe a salad with Newman’s Own Balsamic Vinaigrette Dressing, I can help you get a handle on things and help you get the most for your money.

Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale

Let’s start at the top with Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale, the one category best regulated and probably the most honestly marketed style. Chances are you have never tasted this magical elixir. And that’s a pity because it is a revelation in a league with foie gras, French Sauternes, or fresh truffles. It is one of the world’s great luxury comestibles and it exalts everything it adorns. Its name has nothing to do with balsa wood. The Italian word balsam means balm, something soothing, even an ointment, and that it certainly is. Alas, it sells for $100-200 for a tiny 3.4 ounce (100 ml) bottle. That’s about the size of a lot of perfume bottles.

Tradizionale is a far cry from what most of us have come to think is balsamic vinegar. It is dense and viscous, velvety, almost like a syrup when poured. It is shiny mahogany in the middle and sparkling amber along the edges. The perfume is penetrating but, even though it averages about 5% acidity by weight, does not attack your sinuses and make you pull back like normal vinegars, and it is layered with floral and dried fruit essences. In the mouth it is velvety, slick, almost oily, like a liqueur, harmoniously sweet and tart at the same time, with a singular flavor of caramel, concentrated raisins, dried figs, dates, and cherries. When you swallow, it lasts longer than sex.

Tradizionale is made by a complex method invented in the early 1800s, and it is made only in and around two small neighboring towns in northern Italy, Modena and Reggio Emilia. The production and quality is supervised by three separate and competing consortiums of producers who act as a regulatory agency, trade association, and marketing arm.

The exact methods differ slightly from producer to producer, but the general approach is the same. It begins by harvesting a variety of locally grown grapes, most prominently the white variety, trebbiano, crushing them, and then coarsely filtering the mash, called mosto. The mosto is then cooked (cotto) in an open vat at 175-200°F (79°C-93°C) for a day or two, reducing it to about half the volume.

The concentrated cotto mosto is then inoculated with a “mother of vinegar”, a batch of vinegar alive with a culture of aceto-bacteria. They convert it to acetic acid, better known as wine vinegar. The ingredients list on the label is simple: Mosto d’uva cotto (literally “must of grapes cooked”).

The vinegar begins aging in large wooden barrels and stored in the attic, yes, the attic, not the cellar, of the acetaia where the living liquid is subjected to the heat of summer and the freezing cold of winter.

The attic contains several lines of 5-10 barrels, called batteria, each decreasing in size, with the first one about 100 gallons, and the smallest about 10 gallons. Each barrel contains progressively older vinegar. Every winter about 25% of the vinegar in the smallest barrel is removed and bottled, and younger vinegar from the barrel next in line replaces it. This “topping up” siphoning cascade continues on up the line, with young vinegar replacing the older vinegar that has moved on down the line. The process is similar to the solera process used to make fine sherry in Spain.

The bung holes of the casks are not stoppered, only covered with gauze to keep dust and flies out, so over the course of a year about 10% evaporates. Called the “angels’ share”, this evaporation significantly reduces the amount of vinegar and concentrates the flavors of the remaining fluid. There are also significant losses to sediment that settles out with age.

In addition, each barrel is usually made from a different wood, among them oak, chestnut, cherry, mulberry, ash, and juniper. The acidity extracts unique flavors from each tree, conferring complexity to the end product. The initial casks are usually more porous wood, perhaps chestnut, to promote evaporation and concentration of the vinegar and the smaller casks, with the older vinegars, are made of harder wood such as oak.

The finished vinegar is tasted by assaggiatori, expert tasters, from the consorzio, the consortium, to which the acetaia belongs, and, if it passes, is bottled by the consorzio. Reggio Emilia has a consorzio, and Modena has two who don’t get along. Modena has a unique trademarked bottle shape, with a long neck, globe middle, and rectangular base, only 3.4 ounces (100 ml), shown at left. Reggio Emilia has a different trademarked bottle shape, like a bowling pin with a flared bottom, also 3.4 ounces (100 ml), shown at right.

Tradizionale producers have attempted to grade their vinegars based on their ages. They speak of them as 12, 18, or 25 year old, and older. But remember, because younger vinegars are added to the smallest barrel each year, the actual age of the vinegar is impossible to know. That’s why, by law, tradizionale cannot be labeled with an age statement or a vintage date, and why you should be skeptical of any age statement you see on a label or in an advertisement.

In Modena, according to Consorzio Tra Produttori di Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena, the younger tradizionale, called affinato, is bottled with a white top, and the older one, which is often labeled extra vecchio, extra mature, has a gold top. In Reggio Emilia, according to Consorzio Produttori di Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Reggio Emilia, there are three grades, crimson top for affinato, silver top for a middle age called vecchio, and gold top for extra vecchio. In case you’re curious, there is another official body regulating tradizionale in Modena, the Consorzio Tutela Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena. It was formed in a dispute with the older Consorzio. Further explanations are not worth the effort.

In Modena there are only about 100 producers and they make at total of about 80,000 bottles per year and Reggio Emilia has about 60 producers who make 25,000 bottles per year. Of the 75,000 bottles total, about 40%, or 30,000 bottles, are extra vecchio.

Buying Guide. All the tradizionale vinegars I tasted were excellent and are highly recommended if you can afford them. They are subject to the law of diminishing returns as often applied to wine, the older extra vecchio is much more expensive than the affinato, and it is usually better, but is it worth the price? That’s a matter of how wealthy you feel. I have seen affinato for as little as $100 on the internet, and extra vecchio typically is in the $200-500 range for a 3.4 ounce (100 ml) bottle. I have purchased direct from producers in Italy for significantly less, shipping included.

Here’s a link to the affinato I buy for myself and as gifts

A word of caution. I have seen one producer, Delizia, marketing a “Traditional Style” Balsamic Vinegar. Although it is a nice vinegar, it is nowhere close to the real thing and its name would probably be illegal in Italy.

Condimento Balsamico

Condimento Balsamico, also called Balsamic Must, is made similarly to tradizionale, with cooked grape juice (must). Condimento is made with a batteria, but the finished product is younger, typically 3 years, and a lot less expensive, typically $50-100 for a 17 ounce (500 ml) bottle. It is not uncommon to add a bit of wine vinegar for extra acidity. Condimento production is not regulated, so there is no telling if they are legit or just sweetened, thickened wine vinegar. Most condimenti are made by tradizionale producers, and for that reason I tend to believe most are legit. Those I have tasted have been very good, and they may be the best value in balsamico. They are not as thick, sweet, rich or complex as tradizionale, but they’re good enough for drizzling and special occasions. But without any control, it is probably just a matter of time until the term condimento becomes meaningless. I once ordered a Cavalli Condimento Balsamico on Amazon, 500 ml for $45.57. The picture of the label was small and blurry. When it arrived I noticed the word balsamico was not on the label. It turned out to be a wonderful balsamico, but did not taste like a Condimento, and as a result I probably paid $20 or more than I should have. Buyer beware.

Balsamic Vinegar di Modena (BVM) or salad balsamic

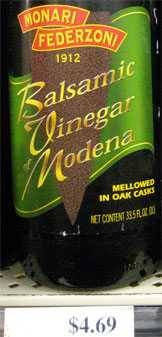

Balsamic Vinegar di Modena (BVM) is usually cheap. Most are $5 to 10 for a 16.9 ounce bottle (500 ml) in our grocery store. The one above is only $4.69 for 33.5 ounces (1 liter)! The better ones are brown, like a red wine in viscosity, slightly sweet, very tart, with a long aftertaste. The ingredients list usually has “wine vinegar, cooked grape must, and caramel color.” They are typically 6% acidity, they make fine salad dressings, sauces, and marinades, and I cannot live without them in my kitchen. The production process bears little resemblance to the process for tradizionale, and they are not close to tradizionale in taste. The tradizionale consortia refer to these mass produced vinegars as “industrial vinegar.” I prefer to call them “salad balsamic.” Yet the media continues to popularize the notion that they are made with a batteria. Not.

The problem is that some salad balsamic is watery and insipid tastes like crudely made fresh wine vinegar and smells like apple cider, banana, geraniums, and even solvent. These are not desirable characteristics. And the prices can get up to $50 per bottle. There’s no sure way to tell from the bottle what you are getting, and that makes it hard to use in recipes.

BVM production specifications require that all raw materials and production take place in Modena and Reggio Emilia and that the grapes are Lambrusco, Sangiovese, Trebbiano, Albana, Ancellotta, Fortana, and Montuni. They must be aged in barrels for 60 days only at a temperature of 60°F (15.5°C). They then must pass a tasting panel.

Red tag and white tag. Beginning in 2001 some of the producers formed a consortium to improve quality and image, the Consorzio Aceto Balsamico di Modena (CABM). It now has about 20 members, but their production and labeling rules are much less stringent than the tradizionale consortiums, and the methods of production vary widely. Sadly, the CABM doesn’t do much to help consumers.

They came up with a red tag for the top of their bottles that supposedly certifies it has passed a taste test and spent three years barrels, and a white tag is supposed to certify that it has aged more than three years. But it’s hard to be sure of that since the blending of vinegars in a batteria means that surely some of the vinegar is younger, and perhaps some is even older.

Grape leaf ratings. In 2001 yet another association came along, the Assaggiatori Italiani Balsamico (Italian Balsamic Vinegar Tasting Association). AIB instituted a rating system based on taste, but not all producers participate yet. If a vinegar has been submitted for tasting, a colored band is printed on the label with 1-4 grape leaves (shown at right). According to Fini, a leading producer, one leaf on a red band indicates a vinegar with “a classic flavor, light and slightly pungent, suitable for salads and everyday use.” Two leaves on a silver band indicates a more syrupy consistency and “a smooth flavor, which matches well with grilled dishes and oven-roast vegetables.” Three leaves on a gold band designates “a vinegar with a distinct, rounded, full flavor, ideal for meat and fish dishes and hot sauces.” Four gold leaves on a black band are given to “an exceptionally dense condiment with a superb flavor, which comes from the ageing of the very best reserves: perfect for exclusive recipes, on fruit, ice-cream and with Parmigiano cheese.”

In my experience there is a quality difference as one adds grape leaves to the label of each producer, but there is no equivalence between producers. For example, the Fini four leaf is better than the one leaf, and the Mazetti 4-leaf is better than its one leaf, but the Fini four leaf is a lot better than the Mazetti four leaf.

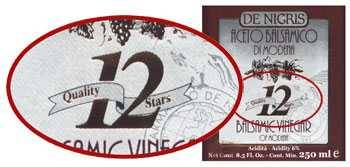

There are other bottles that have age claims on the label. They sell for a pretty penny, and some taste mighty nice, but because there is no rule regulating age statements, there’s no guarantee that it really is that old and worth the price. One popular brand, de Nigris, which sells for about $25 for an 8.5 ounce (250 ml) bottle, has a big 12 on the label, giving the impression that it is 12 years old. But the fine print behind the 12 says “star quality.” One can only guess what “12 star quality” means.

Bottom line. For now, if the label says Balsamic Vinegar di Modena or something similar, it’s bigtime caveat emptor.

White balsamic

This is an example of how the word balsamic has been corrupted. Technically, there is no such thing as white balsamic vinegar. As we have seen, tradizionale and even salad grade balsamics are made by boiling grape juice and aging it or coloring it to make it brown. The trend is to take plain old white wine vinegar and add a little boiled white grape juice and voila, white balsamic. This is what happens when there is no real label regulation.

Specialty vinegars labeled balsamic

Balsamic cream and balsamic syrup. These are Balsamic Vinegar di Modena that have been reduced to a syrup.

Flavored balsamics. These have flavor extracts like orange, lemon, cherry, even coffee added.

“Balsamics” from other countries

Venturi Schutze of British Columbia, Canada, makes a very good balsamic comparable to the best BVMs.

“O” California Balsamic is similar to a good BVM and better than most.

Selecting balsamic

For marinades. Buy any inexpensive brand of BVM. Balsamic Vinegar di Modena is easy to find in supermarkets, olive oil stores, and gourmet stores. Buy a few and taste them like you would wine.

For sauces or salad dressings. Buy a good BVM, perhaps 2-4 grape leaves on the label, and slowly cook it down to 1/2 to 1/3 the volume.

For drizzling on cheese, fruit, or meat. Get condimento. I would never cook with this expensive and delicate delicacy, nor would I bury it in a sauce, or make a salad dressing with it. It is for drizzling at room temp on garden fresh August tomatoes, Parmigiano-Reggiano, steaks, or baked potato. If you are buying condimento, take the advice of a trusted merchant who has tasted many.

For special foods, special occasions, or special guests. Get tradizionale. Drizzle it on seared foie gras, carpaccio, or even fresh fruits like strawberries, pears, and peaches. It is also fabulous on vanilla ice cream. You heard me. If you are buying tradizione, be sure to look for the distinctive trademarked bottle shapes and sizes, look for the color coded capsules from Modena and the color coded labels from Reggio Emilia, and be suspicious if it costs less than $100.

Amazon lists a wide range of balsamico styles from several merchants and producers

Make balsamic syrup

You can amp up the flavor of cheap balsamic by boiling it until it is reduced by half and about the thickness of vegetable oil. This is by no means a substitute for the high end balsamics, but it does concentrate the flavor and richness, and it makes a lovely syrup that is sweet and tart, similar to condimento, and suitable for drizzling. Just be careful and keep an eye on the boiling. There’s sugar in balsamic and it can burn. In fact, some cheap balsamics have so much sugar they can turn to candy!

Some recipes with balsamico

- Italian Vinaigrette Salad Dressing

- Caprese Tomato Salad

- Tuscan Marinated Ribs

- Lamb Loin Chops in Sheep Dip

- Drunken Cranberries

- Grilled Asparagus

For more info

Here is contact info for the Consortia who regulate and market balsamico, especially useful if you would like to visit an acetaia.

Consorsio Tutela Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena – TABT

Consorzio Aceto Balsamico di Modena (Modena Balsamic Vinegar Consortium) – CABM

Produzione Certificata Consorzio

Accademia Italiana Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena

Assaggiatori Italiani Balsamico (Italian Balsamic Vinegar Tasting Association) – AIB

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators