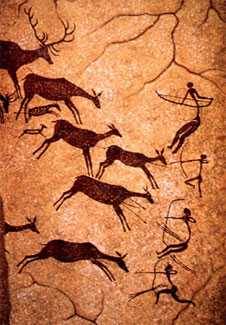

Contrary to mythology, barbecue was not an American invention. Barbecue is older than homo sapiens and anthropologists even think that it was mastery of fire that permanently altered our evolutionary path and it is this primeval link that makes us still love cooking over flame. And cooking low and slow with smoke may have come later but it came far earlier than most American barbecue enthusiasts think.

Around one million years ago Homo erectus, the homonid just before Neanderthal man, first tasted cooked meat.

Nobody knows for sure, but here’s how I think it happened: A tribe of these proto-humans were padding warily through the warm ashes of a forest fire following their noses to a particularly seductive scent. When they stumbled upon the charred carcass of a wild boar they squatted and poked their hands into its side. They sniffed their fragrant fingers, then licked the greasy digits. The magical blend of warm protein, molten fat, and unctuous collagen in roasted meat is a narcotic elixir and it addicted them on first bite. They became focused, obsessed with tugging and scraping the bones clean, moaning, and shaking their heads. The sensuous aromas made their nostrils smile and the fulsome flavors caused their mouths to weep. Before long mortals were making sacrifices and burnt offerings to their gods, certain the immortals would like to try their heavenly recipes.

Cooking makes it easier for animals to extract energy from food. That meant that there were more calories available for larger brains, which of course was an evolutionary advantage. It also took much much less time to eat, leaving time to hunt, socialize and form tribes and communities, and procreate.

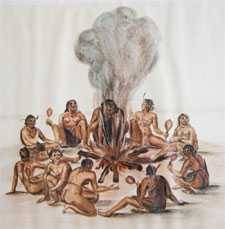

Evolution favored traits that enhanced the ability of these early homonids to hunt and eat cooked meat: Smaller hips and flatter feet for running speed, better hand articulation, communication skills, and smaller jaws. Eventually they learned to domesticate dogs to help with the hunt, and then they learned to herd and husband the animals that tasted best. The family circle and tribal structure evolved so that men became hunters and women became cooks. Ergo, the first pitmasters were probably women.

In 2007 Israeli scientists at University of Haifa uncovered evidence that early humans living in the area around Carmel, about 200,000 years ago were serious about barbecue. From bone and tool evidence, these early hunters preferred large mature animals and cuts of meat that had plenty of flesh on them. They left heads and hooves in the field. Three of their favorites were an ancestor of cattle, deer, and boars. From burn marks around the joints and scrape marks on the bones, there is evidence that these cave dwellers knew how to cook.

Early barbecue cooking implements will likely never be found because they were probably made of wood. The first meats were probably just tossed into a wood infereno.

They quickly learned that the food tasted better if the food was held above or to the side of the fire. According to barbecue historian Dr. Howard L. Taylor, the first cooking implements were almost certainly “a wooden fork or spit to hold the meat over the fire.

Eventually they built racks of green sticks to hold the food above the flames, and learned that the temperature was easier to regulate and the flavor better if the if they let the logs burn down to coals before the meat was put in place.

Spit roasting is common around the world and for many years was the major barbecue cooking method. Baking an animal, vegetables, or bread in a hot pit in the ground was also an early development. Wooden frames were later used to hold meat over the fire, but they often held the meat well above the fire to keep the wood from burning, which resulted in the meat cooking slowly and absorbing smoke. The gridiron [similar to a grate on a modern grill] was developed soon after the Iron Age started, which led to grilling as we know it. Iliad, Book IX, Lines 205-235 and The Odyssey, Book III, lines 460-468 mention spits and five-pronged forks used to roast meat, basted with salt and wine at outdoor feasts in ancient Greece. Such feasts at the end of a battle or long march were common throughout history.” Below is a grill from the Stoö of Attalus Museum in Athens in a photo by Giovanni Dall’Orto. It is estimated to be from sometime between the 4th and 6th century BCE.

Smoked foods not only tasted swell, they kept longer. We now know this is because there are antimicrobial compounds in smoke, because smoke drove off flies, and because slow smoking dehydrated foods and bacteria need moisture to grow. In the days before refrigeration, smoking, drying, and salting meat were clever strategies for preserving perishable foods. This allowed hunting tribes to make a kill and, unlike other animals, they did not have to gorge themselves before the prey spoiled. If they were migratory, they could smoke, dry, and salt foods and take it on the road with them.

Barbecue and the Bible

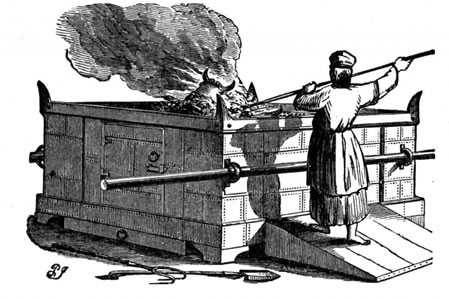

The Hebrew Old Testament contains what may be the first detailed plans for the design of a barbecue. In Exodus, chapter 27, probably written somewhere between 1300 and 1500 years before Christ was born, after Moses brings down the 10 Commandments, he tells his flock that God wants them to construct a tabernacle with an ark for the Covenant and an altar for burnt offerings of animals.

It stood about 4 1/2 feet high about 7 1/2 feet long, contained fleshooks, firepans, ash pans, shovels, basins, a grate, and tie downs to attach the animal before the sacrifice. Like today’s big rigs, it was portable. It did not have wheels, but poles on each side so it could be carried by hand.

In chapter 29 there are instructions of how to prepare the sacrifice of a young bull and two rams and describes the process as “a sweet savour, an offering made by fire unto the Lord.” Apparently the scent was all the Lord wanted because Aaron, Moses’ brother and the priest in charge, and his associates, were allowed to eat much of the sacrifice.

Leviticus 1 starts to sound like a cookbook with instructions for slaughtering and preparing burnt offerings of a bull, turtledoves, pigeons, sheep, goats, fruits, corn, and bread as well as the laws for kosher eating. They were instructed to take an unblemished animal (apparently their Lord appreciated quality meat), remove the kidneys and the fat on them, and the caul fat above the liver (the best fat on the animal) and burn it. No cheap cuts for this god!

China, India, and Japan

Many scholars think techniques for low and slow smoke roasting began in China where some early kitchens had special devices for smoking meats. A wonderful speculation on the discovery of the delights of fire-roasted pork was penned by the English essayist and humorist Charles Lamb in 1822. He tells of the Chinese peasant Bo-bo who, long long ago, accidentally burned down his father’s cottage and the pigs within. Bo-bo not only discovers barbecue, but then embarks on a career of arson, burning down the neighborhood one cottage at a time to sate his hunger for roast pork. Click here to read Lamb’s tale, “A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig.”

In ancient China, India, and Japan, food has been cooked over coals in ceramic urns for thousands of years. In India they are called tandoors, and in Japan they are called kamados. Here is one from China. Click the link to learn more and see some of the many popular modern kamados. Here is an ancient Chinese ceramic charcoal oven still in use cooking buns stuck to the wall of the oven. Indians cook their bread, naan, the same way.

Old World influences

In Europe, artists have painted pictures of barbecues since pig hair bristles were first wrapped around a stick to make a brush. The ox roast in the painting below took place in Bologna, Italy in the 1531.

Early cooks learned quickly that flavor, tenderness, and juiciness were related to how foods were cooked and how long. Museums are full of clever gadgets built to improve palatability. Cooking in open fireplaces over wood and with plenty of smoke was commonplace, and all manner of clever iron grids, reflectors, and rotating devices were developed.

Here is an elaborate clockwork rotisserie mechanism mounted in a fireplace that I photographed in a 13th century castle in Europe. The cook would turn a handle that would wind a weighted cable around an axle. The weight would slowly descend and the mechanism would slowly rotate the food above the coals. Leonardo da Vinci invented one. He also invented one with a fan in the flue that turned with the rising hot air and it turned the spit. In English inns it was called a smoke jack.

England has long been a nation of beefeaters, and in the Middle Ages they were devoted to cooking over flame and sneered at roasting in an oven. Hams and beeves (beef) were hung in the chimney above the fireplace to smoke and gently roast. Cranking the rotisserie by hand usually fell to young boy until somebody had the a bright idea. The “turnspit dog” was first mentioned in print in 1576, and the concept became so popular that many homes and inns installed a system. Breeders even created a canine especially designed for the task with short legs, perhaps an ancestor of the corgie. The breed is extinct, but the Abergavenny Museum in Wales has a stuffed Canis vertigus on display.

Not many dog powered turnspits are left, but there’s a beauty in a restored 1700s Georgian pub in The George Inn in Wiltshire, near Bath. There is at least one other dogtisserie at Number One Royal Crescent in Bath. The picture above of a Turnspit dog hard at work in Newcastle is from the book, Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales by Henry Wigstead published in 1799.

The international gastronomic society, Chaîne des Rôtisseurs is based on the traditions and practices of professional French meat roasters. Their written history has been traced back to 1248. King Louis XII awarded them an official coat of arms in 1610. It consists of two crossed turning spits and four larding needles, surrounded by flames of the hearth on a shield encircled by fleur-de-lis and a chain representing the mechanism used to turn the spit. Today’s Kansas City Barbeque Society is in some way, a cousin of the Chaîne.

Somewhere along the way someone invented the smokehouse. I’m guessing it was an early cook trying to escape from the rain, so he hung some skins over the fireplace and huddled beneath. Eventually it evolved into an something like this Alaskan smokehouse from the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, by Dr. Leuman M. Waugh, 1935. It was a simple sapling frame, a pitched roof of sticks covered in skins, with beams to hang the salmon filets. Drawings of smokehouses like this go back centuries.

Grilled and smoked meats, especially pork and sausage, are deeply woven into German and Czech culinary traditions, and this influence is particularly strong in the Carolina and Texas barbecue traditions where their immigrants settled. Above is an excerpt from a painting from the 1600s by an unknown Flemish artist titled “Hier wird um wenig geld” (“Here, for little money”). It shows a women selling grilled vegetables outdoors, one of the first representations of a grill I have seen.

Spain and New World barbacoa

Let’s make up for an injustice. Nobody gives the Spanish Empire proper credit for its role in laying the foundation for modern American barbecue. Their aggressive exploration and exploitation of the Caribbean, the Southeastern corner of North America, Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Philippeans brought cattle, hogs, sheep, goats and European foodways, including spit roasting, to the New World. Some gastrohistorians have remarked that more than the Spanish, hogs conquered the New World because they became so popular with Amerindians and settlers. And while they were at it the conquistadors brought disease and slavery to their conquests, decimating huge populations.

On the way home the adventurers brought back gold, tomatoes, potatoes, corn, chile peppers, chocolate, and more (see sidebar). But right here we see the basic ingredients of contemporary American, Mexican, and other cuisines, including modern barbecue. They also brought back the Taino Indian word and design for the barbacoa.

In 1492 Christopher Columbus made the first of his four voyages from Spain to the New World landing on the island he called Hispaniola, known today as the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and then went on to Cuba, and the Bahamas. On his first voyage he coined perhaps the oldest bromide in culinary literature. In his diary he wrote of seeing a “serpent” about six feet long that was probably an iguana. His men killed it, ate it, and he remarked that “the meat is white and tastes like chicken.”

Over the next 11 years he came back three more times and set foot on numerous Caribbean islands, Central America, and even northern South America. His tales of the strange new universe, its people, animals, foods, and riches, launched a flurry of explorations by Spanish conquistadors as well as French and English adventurers.

On his second voyage he is believed to have stopped in the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa and picked up 20 to 30 cattle, mostly pregnant females descended from Portuguese and Spanish stock brought there a few decades earlier. Within three weeks they were grazing contentedly on the lush greenery of Hispanola and within a few years conquistadors brought them to Mexico where vaqueros, Mexican predecessors of cowboys, drove them north to Texas.

The people they encountered in the Caribbean were unfortunately called Indians since Columbus had been seeking a route to India. They were members of Arawak tribe, a sub tribe called Taino, and further north in the Bahamas, Lucayans. I shall call them Amerindians to avoid confusion.

According to an email from barbecue historian Dr. Howard Taylor “Oviedo is reputed to be a reliable source for translation from these American Indian dialects into Spanish because of his dedication to accuracy and experience as Chronicler to Charles V of Spain. Arawak tribes and dialects of the Arawak language were widely distributed across the West Indies, Central America, and Northern South America.”

Of course we will never know precisely what the Taino word was since they had no writing system. I’m guessing it only sounded like barbacoa to the Conquistadors since people usually mispronounce foreign language words. Nobody will ever know for sure, but barbacoa, especially the “-oa” at the end, sounds mighty Spanish to me. Other European explorers reported home that natives in northern South America, especially Guiana, may have called their version of the barbacoa a babracot or babricot or barboka. These are possibly dialects of the many tribal languages or further clumsy attempts to mimick the native words.

During the European explorations of the 1500s Arawak tribes were not native to areas now in the United States, but some Arawak tribes moved into southern Florida during the mid-to-late 1600s. “Florida” which was the Spanish name for all the land they claimed, extending north through modern Virginia and even into New York and west through Louisiana. The English did not arrive in Jamestown, VA, until 1607, and the French did not settle in New Orleans until 1690. Present day Florida was populated with many different tribes, among them the Timucua, Apalachee, Calusa, Tocobaga, Ais, Mayaca, and Hororo, and most of them had adapted the barbacoa and accounts of other explorers show it in use by other tribes far north and west.

In fact, the engraving above shows a barbacoa used by Amerindians in the mid 1580s in what is today North Carolina. It was done by the European engraver and publisher Theodor de Bry and based on a watercolor by a settler, John White. Similar illustrations were made in the 1560s by the first European artist in North America, Miles Harvey and in 1564 by Jacques le Moyne. Note the smoke in the illustration above and the two fish cooking with indirect heat off to the left. The smoke not only cooked the fish, it kept away flies and animals, and preserved it for storage.

The barbacoa however, was the name for a wooden rack, not just a cooking device, because other early explorers described similar devices being used to store food above the damp ground and out of reach of animals, as well as a bed for sleeping above the snakes and insects. Oviedo described “a loft made with canes, which they build to keep their maize in, which they call a barbacoa.” According to the Historical Dictionary of Cuba Second Edition by Jaime Suchlicki, the Ciboney Indians of Cuba even called their primitive dwellings barbacoa. The Bishop of Cuba, Gabriel Diaz Vara Calderon in 1675 wrote after a 10 month journey through Florida “They sleep on the ground, and in their houses only on a frame made of reed bars, which they call barbacoa, with a bear skin laid upon it and without any cover, the fire they build in the center of the house serving in place of a blanket.”

A French explorer describes a cooking barbacoa here: “A Caribbee has been known, on returning home from fishing, fatigued and pressed with hunger, to have the patience to wait the roasting of a fish on a wooden grate fixed two feet above the ground over a fire so small as sometimes to require the whole day to dress it.” That’s low and slow cooking, folks.

In this photo above we see a barbacoa portrayed in a diorama I saw at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Made in 1920 it is said to portray native Americans in the Chicago area, so if it is accurate, this concept was not just Carribean.

In 1521 Juan Ponce de Leon made his second visit to the land he named La Florida in 1513. The first trip was exploratory. This time he came to colonize and brought with him 200 men including farmers, craftsmen, horses, cattle and other farm animals, and farming tools. The landed near what is today Ft. Meyers on the Southwest coast. The expedition was expelled by natives, de Leon was hit by an arrow, and he died shortly thereafter. But some scholars think some of the cattle remained behind where they were no doubt utilized by the locals.

The DeSoto National Memorial in Bradenton, FL, not far from the place where the Spanish explorer is believed to have landed in 1539 with 400 soldiers, horses, and 300 hogs, the first to inhabit North America, has a small replica barbacoa on display. DeSoto also had with him 2,500 pork shoulders, probably packed in barrels with salt. Bacon was well known and likely came with the explorer.

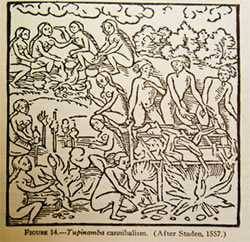

The first to describe the use of the barbacoa for cooking was Hans Stade, a German in the service of Portugal captured by tribes in Brazil in 1547. He escaped and returned to Europe in 1555. His 1557 book “True History” included woodcuts he supervised showing a barbacoa. Here’s how he described the device, which he did not name “When they want to cook any food, flesh or fish, which is to last some time, they put it four spans high above the fire-place, upon rafters, and make a moderate fire underneath, leaving it in such a manner to roast and smoke, until it becomes quite dry. When they afterwards would eat thereof, they boil it up again and eat it, and such meat they call Mockaein.” His accounts include use of the device for cooking human flesh. Incidentally, there are credible accounts of cannibalism in Europe, too.

The first recorded barbecue in the Southeastern US may have featured human flesh. In April 1528, Panfilo de Narváez set out with 400 men and 80 horses from Cuba to explore Florida and search for gold. They landed in the Tampa Bay area and foolishly lost contact with their ships. They were quickly set upon by hostiles and tried to retreat by building boats and sailing for Panuco on the east coast of Mexico in New Spain. A few made it to Texas and over the course of about 2 years their numbers dwindled to 4, among them Cabeza de Vaca. Navarez perished at sea. In spring of 1536, the party made it to the Spanish settlement of San Miguel de Culiacán on the lower San Lorenzo River.

While they were lost, the Spanish governor of Cuba sent out a search party that also ran into trouble. One member of the party, Juan Ortiz was captured by the Ozita tribe. They decided to sacrifice him by torture and tied him to a barbacoa-like device. The chief’s daughter took pity on the slowly roasting man and convinced his father to release him. Ortiz was not flipped, so he was permanently scarred on his back. Ortiz lived for years with the tribe until he was rescued by a party led by a fellow Spaniard, the explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto (shown here). Ortiz joined de Soto as an interpreter.

After helping conquer the Incas in Central America, de Soto had sailed from Cuba to Tampa Bay in 1539. He brought about 650 men, many horses, dogs, and Spanish hogs, which were not native to the continent. He then set out exploring and pillaging what is now the Southeast of the US.

According to Charles Hudson’s 1998 book Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando De Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms, on March 25, 1540 a party of about 40 Spaniards led by de Soto invaded a village in what is now Georgia and found venison and turkey smoke roasting on a barbacoa-like device. Although the word had not been brought north by Indians yet, DeSoto called it a barbacoa because he had probably heard the word in Spain. Famished from a 35 hour ride, despite the fact that it was Holy Thursday, they feasted on the first barbacoa in recorded history.

On May 17, 1540, according to Hudson, they enjoyed another meal cooked on a barbacoa near present day Salisbury, NC: Corn and small dogs.

According to Faulkner’s County: The Historical Roots of Yoknapatawpha, 1540-1962 By Don Harrison Doyle, in December 1540, near what is now Tupelo, Mississippi, de Soto collaborated with the Chickasaw tribe on a feast featuring pork from Spain cooked on a barbacoa. The Chickasaws loved their pork barbecue (can you blame them?) and even stole hogs from DeSoto. The Spanish adopted the cooking method and refined it.

They also riffed on it. Somewhere, somehow, in Mexico and Texas, barbacoa came to mean wrapping a cow’s head with leaves and burying it in a pit lined with hot rocks. This technique is still used in Mexico and as far away as Hawaii, but not many practitioners use the traditional cow’s head. One survivor is Vera’s Backyard Bar-B-Que in Brownsville, TX. That’s Armando “Mando” Vera, above, with the pit which holds the heads for about 12 hours. Founded in 1955, in 2020 the James Beard Foundation recognized Vera’s with an “American Classics Award”. Cheek meat is the most popular and it is used for tacos.

Eventually the method of cooking found its way north to the English colonies in Virginia and the Carolinas where they doused the meat with a favorite condiment from home, vinegar. Vinegar remains the major ingredient of most sauces in Eastern North Carolina and South Carolina to this day. In the 1930s the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal government project, interviewed hundreds of former slaves. One Wesley Jones of South Carolina remembered how he cooked hogs for special occasions “Night befo’ dem barbecues, I used to stay up all night a-cooking and basting de meats wid barbecue sass (sauce). It made of vinegar, black and red pepper, salt, butter, a little sage, coriander, basil, onion, and garlic. Some folks drop a little sugar in it. On a long pronged stick I wraps a soft rag or cotton fer a swab, and all de night long I swabs dat meat ‘till it drip into de fire. Dem drippings change de smoke into seasoned fumes dat smoke de meat. We turn de meat over and swab it dat way all night long ‘till it ooze seasoning and bake all through.”

German settlers were fond of mustard on their pork so the classic mustard based barbecue sauce of South Carolina evolved.

The first big barbecue in Texas, according to Taylor, “Was probably held on April 30, 1598, near San Elizario on the Rio Grande, about 30 miles Southeast of El Paso, TX. The leader of the later celebration was Juan de Onate.” Natives were present, and it was a traditional, religious, outdoors feast that included spit roasted wild game and birds and native vegetables in addition to the usual salted pork, hard biscuits and red wine from Spain.

According to etymologist Michael Quinion, William Dampier, in his New Voyage Round the World of 1699, used the word in English for the first time to describe a raised wooden sleeping platform that protected Indians from snakes: “And lay there all night, upon our Borbecu’s, or frames of Sticks, raised about 3 foot from the Ground.” One can assume there was no fire beneath. According to Quinion, the Dictionary of National Biography describes Dampier as a “buccaneer, pirate, circumnavigator, captain in the navy, and hydrographer.” Ironic that the first to use the word in English should be described as a buccaneer since that occupation comes from the French word boucan, “which in turn comes from mukem, a word used by a group of Brazilian Indians, the Tupi, for a wooden framework on which meat was dried.”

Who discovered low and slow as a cooking method?

We’ll probably never know who discovered that cooking at low temps for a long time had a wonderful impact on tough cuts of meat laden with connective tissue and fat, but the first written documentation I can find is from one Benjamin Thompson in 1802. Thompson was born in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1753, he was a schoolmaster at 19, and British loyalist during the Revolution. After the war he moved to England where he was knighted Count of Rumford.

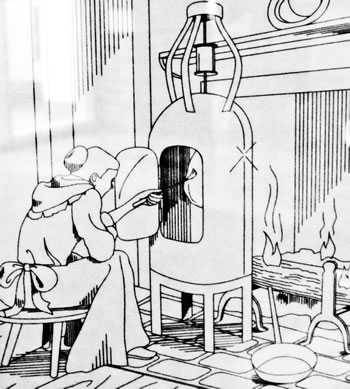

He wrote more than a million words in his books “Essays, Political, Economical, and Philosophical.” In volume III, published in 1802, he devotes more than 300 pages to fireplace design, kitchen design, cooking utensil design, and cooking methods. Above is a link to his original manuscript, with the story of his discovery on page 19. In it he tells of cooking a shoulder of mutton at less than 212°F in a machine he created for drying potatoes.

“After attending to the experiment three hours, and finding it showed no signs of being done, I concluded that the heat was not sufficiently intense; and despairing of success, I went home, rather out of humour at my ill success, and abandoned my shoulder of mutton to the cook-maids.

“When they came in the morning to take it away, intending to cook it for their dinner, they were much surprised to find it already cooked, and not merely eatable, but perfectly done, and most singularly well-tasted.

“When I tasted the meat I was very much surprised indeed to find it very different, both in taste and flavour, from any I had ever tasted. It was perfectly tender; but though it was so much done, it did not appear to be in the least sodden or insipid; on the contrary, it was uncommonly savoury and high flavoured. “It was neither boiled, nor roasted, nor baked. Its taste seemed to indicate the manner in which it had been prepared: that the gentle heat to which it had for so long a time been exposed, had by degrees loosened the cohesion of its fibres, and concocted its juices, without driving off their fine and more volatile parts, and without washing away or burning and rendering rancid and empyrumatic its oils.”

The evolution of barbecoa into barbecue

Before white men landed in the new world, native Americans had begun developing cooking styles and methods similar to Europeans. Soon after the explorers arrived natives began adapting techniques learned from the invaders. Here is a simple wood burning stove made of mud found in California. It is fitted with a steel plate that could act as a griddle, and it could be replaced by a gridiron for grilling.

In colonial times, long before gas and electricity, almost all food was cooked with wood. The fireplace and hearth also doubled as a cooking center, with rotisseries and side ovens warmed by the fire as seen above in the Old Stone House, built in 1765 in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC. in the lower left corner is a hand cranked rotisserie:

Below is a device called a bottle jack or roasting jack that had a spring mechanism that rotated the meat, a drip pan to collect juices, and a rear door for basting.

George Washington had a large smokehouse at his plantation at Mt. Vernon, VA (shown here). On May 27, 1769, the aristocrat, not yet our President or even a General, wrote in his diary (2:154) “Went in to Alexandria [VA] to a Barbecue and stayed all Night.” So the tradition of partying all night with outdoor cooked meat can be traced back at least this far. Washington even hosted “a Barbicue of my own giving at Accatinck” in September 1773. In 1793, after the ceremony for the placing of the cornerstone of the United States Capitol, a 500-pound ox was barbecued.

Alas the exact menus and cooking method are unknown, but pork and ox were popular at the time, and whiskey would have been served. Washington even built a distillery at Mt. Vernon in 1797.

According to the book Dining with the Washingtons: Historic Recipes, Entertaining, and Hospitality from Mount Vernon edited by Stephen A. McLeod, “Barbecues were lively social events…” and Washington brought 48 bottles of French claret to one. “During the Christmas season of 1773, he came outside to find his stepson and some visiting friends ‘pitching the bar’ which was probably similar to horseshoes. Painter Chales Willson Peale later recorded that ‘[Washington] requested to be shown the pegs that marked the bounds of our efforts; then, smiling, and without putting off his coat, held out his hand for the missile. No sooner… did the heavy iron bar feel the grasp of his mighty hand than it lost the power of gravitation, and whizzed through the air, striking the ground far, very far, beyond our utmost limits. We were indeed amazed, as we stood around, all stripped to the buff, with shirt sleeves rolled up, and having thought ourselves very clever felloes, while the colonel, on retiring, pleasantly observed, ‘When you beat my pitch gentlemen, I’ll try again.””

In his mansion at Mt. Vernon, George Washington’s kitchen had a simple pulley driven rotisserie in front of the large hearth. On the wall there hung several other spits of varying length.

The flavor of slowly smoke roasted meat with flavorful sauce grew in popularity, especially in the southern US. Many plantations had smokehouses, primarily for preserving meat, especially hams. Slaves did most of the cooking, maintained the smokehouses, and were given responsibility for preparing open pit barbecues for big celebrations such as weddings, holidays, and political gatherings.

Smokehouses were common in the back yards of many homes, and a few even had meat smoking closets attached to their chimney in an upstairs room. A simple damper would divert the smoke from the downstairs fireplace into a sealed room and it would circulate and exit back up the chimney. Andrew Jackson, our seventh President from 1829 to 1837, had a large smokehouse behind his manor at the Hermitage near Nashville, TN. It was built between 1819 and 1821 and has been brought back to its original condition.

In 1826 the first “friction match” was invented by John Walker, a chemist and druggist from Stockton-on-Tees in England. He dipped a stick of wood in a paste of potassium chlorate, sulfur, and other compounds, let it dry, and then dragged it across sandpaper. Since then many bazillion have been sacrificed in attempts to light barbecues.

In the pre-Civil War South, Master got to eat the best cuts of meat. They ate the tenderloin from along the pig’s back, “high on the hog” (yes, that’s where the expression came from), while the slaves got the tougher, more gristle-riddled cuts. Raw pork was often pickled by storing in a barrel of brine. It didn’t take them long to learn the concepts of low and slow cooking with smoke to make the tenderest most juicy meats from these less desirable cuts. Kindlier masters would reward their slaves with barbecues at Christmas and Independence Day, irony missed, I’m sure. In the engraving by Horace Bradley shown here, from Harper’s Weekly in July 1887 titled “A Southern Barbecue” you can see the typical setup: A shallow pit with green wood sticks to hold the animals, two experienced old pitmasters, and a young apprentice.

In 1867, just after the end of the Civil War, after all the slave cooks were freed, a Georgia widow Mrs. A.P. Hill published Mrs. Hill’s New Cook Book dedicated “to young and inexperienced Southern housekeepers… in this peculiar crisis of our domestic as well as national affairs”. It contains the first reference I have found for a sauce for barbecue. It is mostly butter and vinegar.

The first mention of “barbecue sauce” I have found was in the Bolivar Bulletin from Hardeman County, TN in 1871. The author of an article thanks a Dr. J.H. Larwill for “a fine lot of Barbecue Sauce, of his own invention. For fresh meats of all kinds it cannot be excelled.”

The first commercial barbecue sauce may have been made by the Georgia Barbecue Sauce Company in Atlanta, GA. I have found an ad for it in the Atlanta Constitution in 1909. In 1948, H.J. Heinz introduced the first nationally distributed barbecue sauce. Since then there have been a gazillion brought onto the market. Click here for more about the history of barbecue sauces and their regional styles. Every neighborhood BBQ joint has their sauce in bottle and the grocery store shelves are bulging with them. Click here for some of my faves.

President US Grant had a state of the art wood burning stove installed in his home in Galena, IL, shown above. It provided heat, had several surfaces and chambers for cooking, and even a chamber for smoking.

In 1913, Martha McCullogh-Williams wrote Dishes And Beverages Of The Old South. Born in 1848, she was a teenager through the Civil War, and her family had slaves. The book has many recipes taught to her by her black Mammy. She describes a barbecue that is similar to other accounts from the era: “The animals, butchered at sundown, and cooled of animal heat, after washing down well, are laid upon clean split sticks of green wood over a trench two feet deep, and a little wider, and as long as need be, in which green wood has previously been burned to coals. There the meat stays twelve hours — from midnight to noon the next day, usually. It is basted steadily with salt water, applied with a clean mop, and turned over once only. Live coals are added as needed from the log fire kept burning a little way off. All this sounds simple, dead-easy. Try it — it really is an art. The plantation barbecuer was a person of consequence — moreover, few plantations could show a master of the art. Such an one could give himself lordly airs — the loan of him was an act of special friendship — profitable always to the personage lent. Then as now there were free barbecuers, mostly white — but somehow their handiwork lacked a little of perfection.”

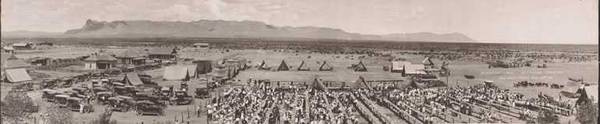

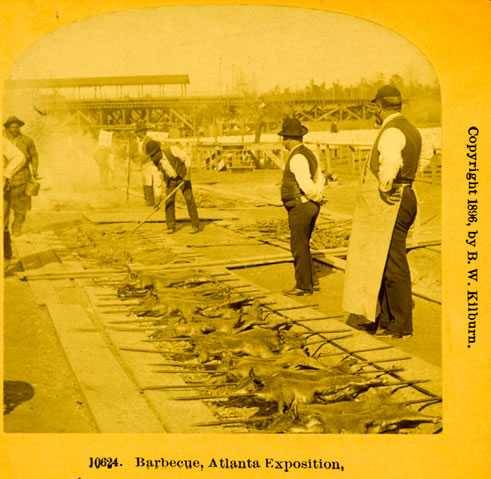

Barbecues were not common in the 1800s. They were for special occasions and events such as July 4, weddings, reunions, and especially political rallies. On October 12, 1844 The Daily Picayune of New Orleans published this account of a barbecue: “There was a mass meeting at Columbus, Ohio, recently, and something of a dinner, as will be seen by the following list of good things which were provided: 1400 weight of ham; 5700 pounds of beef, mutton and pork; 2100 loaves of bread; 500 pies; 300 pounds of cheese; 10 barrels of cider; 4 wagon loads of apples, and 25 barrels of water; with a large number of chickens, ducks, &c., occupying 1700 feet of table in the grove.” Above is a photo of the annual Old Settler’s Reunion in 1919 in Van Horn, TX. Below is a stereograph by of a barbecue at the 1895 Atlanta Exposition.

Slaves and poor whites ate mostly pork and chicken, but sometimes there was beef, mutton, or fish, depending on where they lived. Corn meal was also a staple, as were greens, especially collards, and beans. Corn, oats, and wheat were often stored in an open air crib on some farms. Some even had potatoes. Molasses from the Caribbean was occasionally available. Liquor and coffee were not uncommon. Peanuts were readily available in Georgia and a faux coffee was made from roasted peanuts and corn. Most of the dairy products, butter, milk, cream, and cheese, went to the big house. Just about everything was fried in the plentiful pork lard.

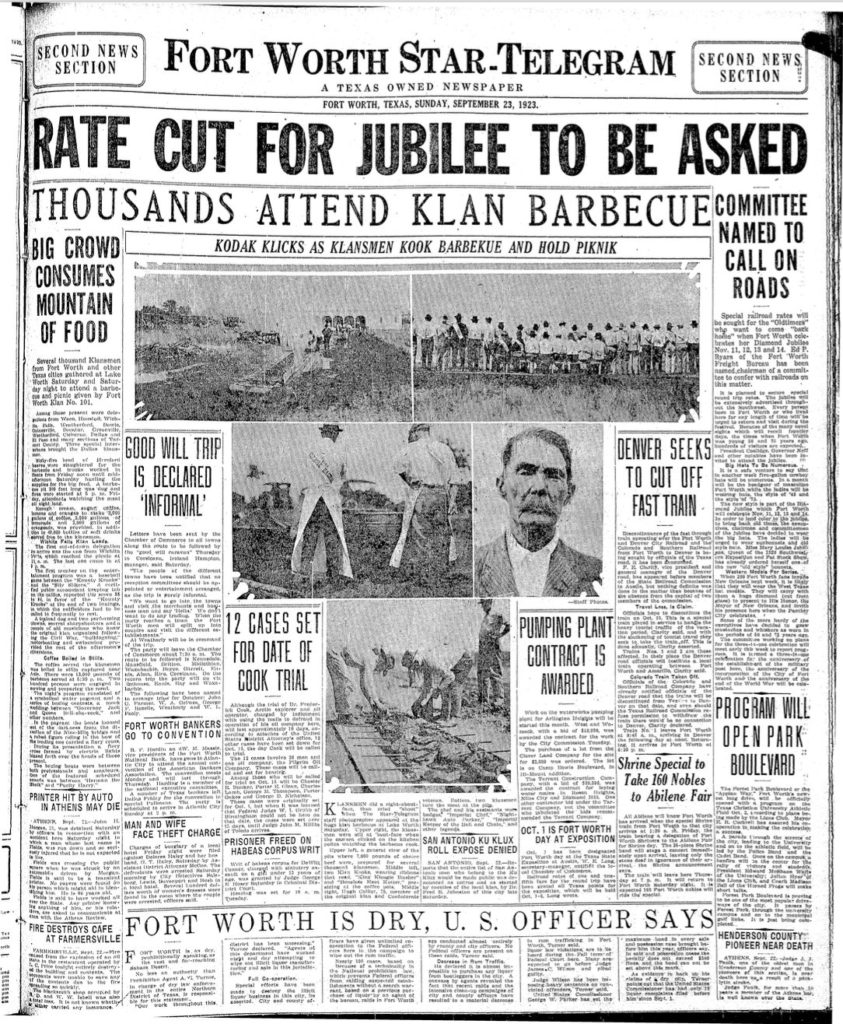

According to excellent reporting by Daniel Vaughn of Texas Monthly, “The (Ku Klux) Klan held its largest and maybe most widely publicized barbecue on the shores of Lake Worth in Fort Worth. ‘Kodak Klicks as Klansmen Kook Barbekue and hold Piknik’ read the September 23, 1923 Fort Worth Star-Telegram headline.” 65 Hereford steers were cooked over a three-hundred-foot-long pit.

This was not haute cuisine. The Tallahassee Sentinel on April 23, 1867 published “Observations in Tropical Florida (from a report made in the Spring of 1866 to Col. T.W. Osborn, by Col. Geo. F. Thompson, and never published before)”. Thompson, sounding like a modern restaurant critic, wrote “The principal food is pork, corn bread, hominy and Hayti potatoes, and what these articles naturally lack in repulsiveness to a refined taste, is fully made up in the abominable manner in which they are cooked and served. To cook a piece of meat, with them, means to fry it to the consistency of a piece of dry hide, and made about as palatable and digestible as live oak chips. The corn bread is usually made (the process I have never learned) so as to be about as delicious and gratifying to the taste as an equal quantity of baked saw-dust.”

He continued: “Grease is used excessively as food; indeed, so repulsive is the manner of cooking, that to a person of refined habits and taste, nothing but the direst necessity and a deep sense of moral obligation to preserve his own life, could induce him to undergo such a diet. People living on the Gulf coast live much better, the art of cooking receiving much ore attention, and the articles of food being more numerous; in the interior, if we judge of the civilization of the inhabitants by the proficiency in the art of cooking and living generally, I fear the would take rank but little above the savages. I have frequently sat down to the table when my olfactories and stomach have joined in a united protest against the task before them, and have only quieted them by the plea of necessity.”

In 1897 Ellsworth Zwoyer patented the charcoal briquet. The briquet really took off when, in the 1920s, Henry Ford, in collaboration with Thomas Edison and EB Kingsford, began commercial manufacturing by making them from sawdust and wood scraps from Ford’s auto plants in Detroit. The Kingsford Company then built the town Kingsford, MI. The company was later sold, and today Kingsford converts more than one million tons of wood scrap into briquets a year. So Ford not only brought the world affordable cars, he created an industry that made backyard barbecue easy. Click here to read about the Science of Charcoal.

Eventually the saplings used to hold the meat over the open pits in the ground were replaced by metal gridirons, and before long the pits were built with stones or bricks above ground. The photo is a stone barbecue in a Long Island park in 1936. Magazines like Sunset in California ran plans for building stone and brick barbecues in your back yard and barbecue was something Dad could do in the suburbs on weekends and after a long day of work.

Barbecue restaurants

In 1830, Skilton Dennis opened what is believed to be the first barbecue business in the US in Ayden, NC.

In Elgin, TX, in 1882, a German American, William J. Moon, began butchering meat and delivering it around town. In 1886 he moved to a new location downtown and The Southside Market started making smoked meats and smoked sausage for home delivery. Smoking was a preservation technique in the days before refrigeration. Ownership changed several times, and in 1968 the Bracewell family took control. Then on September 1, 1983, there was a fire. It took about 10 years but they reopened at its current location.

After all this talk about Southern barbecue, it should be noted that the oldest continually operated restaurant to sell barbecue in a serious manner was opened in New York in 1888 by immigrant Jews and it still exists in the same location making it the oldest uninterrupted barbecue restaurant in the nation. Katz’s Deli opened that year and before you call me an idiot, think about it. Pastrami is usually brisket that has been salted to preserve it, then coated with a rub and smoked. If that isn’t barbecue, I don’t know what is. And if you’ve never had the pastrami at Katz’s, you have no idea what the apogee of the art is. If you can’t get to Manhattan, I can get you close with this recipe for Close To Katz’s Pastrami. And if you question my claim that Katz’s is a barbecue restaurant, well their top seller by far is the pastrami.

In 1891 Golden Rule BBQ opened in Irondale, AL and although it has moved a couple of times it has been open pretty much uninterrupted since then.

Meanwhile, there was a migration going on as freed slaves and sharecroppers started moving north to the industrial centers, among them Kansas City. The flow peaked between 1879 and 1881. Among the migrants was young Henry Perry, born in 1875 in Shelby County, TN, not far from Memphis on the banks of the Mississippi River. At age 15 he got a job on steamboat as a cook. His new job took him to Minneapolis, Chicago, and finally Kansas City where he got a job in a saloon, according to Doug Worgul’s superb book, The Grand Barbecue: A Celebration of the History, Places, Personalities and Techniques of Kansas City Barbecue.

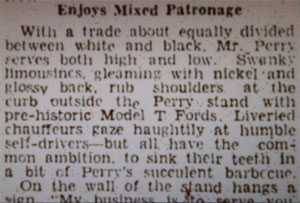

In 1907 Perry started a barbecue stand and eventually moved it indoors, plying a skill he probably learned in Shelby County. It was the first commercial barbecue stand in what is now the nation’s most important barbecue center. According to Worgul “In February 1932, 25 years after Henry Perry first opened his barbecue business, The Call, Kansas City’s leading black newspaper, published an interview with Perry. The article notes that there were in Kansas City at that time ‘more than a thousand barbecue stands.'”

The Call notes that Perry’s food was popular with everyone, although the sauce had a reputation for producing tears it was so hot. Not at all what we think of as KC style today. “With a trade about equally divided between white and black, Mr. Perry serves both high and low. Swanky limousines, gleaming with nickel and glossy back, rub shoulders at the curb outside the Perry stand with pre-historic Model-T Fords. Liveried chauffeurs gaze haughtily at humble self-drivers — but all have the common ambition, to sink their teeth in a bit of Perry’s succulent barbecue.”

Perry was “The Barbecue King” not just because he was first, not just because he eventually had 3 restaurants, but because, as he explained to The Call, “the special way I prepare my meats. Cooking only over a fire made from hickory and oak woods the meat gets that delicious flavor which is the cause of the tremendous popularity of barbecued meats.”

Among Perry’s and disciples were Arthur and Charlie Bryant who opened Arthur Bryant’s in 1930. The KC landmark was called the nation’s best restaurant by New Yorker columnist Calvin Trillin. It still considered a required pilgramage to barbecue lovers around the world. Perry died in 1940, but today KC has more barbecue restaurants per capita than any city in the world. It is, in the words of Kansas City Barbecue Society Founder Carolyn Wells, “The Constantinople of Barbecue”.

Nobody knows when the first barbecue restaurant was opened. Some say it was Perry’s in Kansas City in 1907, but I have found references to barbecue restaurants in old newspaper going back to Flemings barbecue restaurant on Decatur Street in the Atlanta Constitution on October 30, 1897.

Early barbecue restaurants cooked in dirt pits out back, but weather and municipal health laws forced them indoors. The first commercial indoor pits were probably brick, similar to the brick pits still popular in Texas today like the oldie goldies still in use at Smitty’s in Lockhart, TX. They simply mimic the outdoor pit, but lift them above ground. There’s an expanded metal cooking grate, and two to three feet below, glowing hardwood embers.

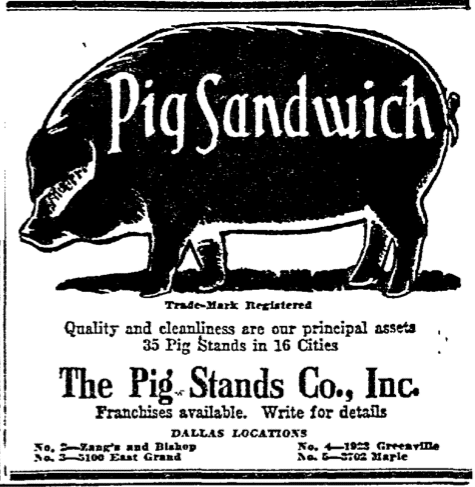

The world’s first drive-in restaurant was The Pig Stand in Dallas Ft. Worth area in 1921. America’s Motor Lunch offered dine in your car convenience and featured the Famous Pig Sandwich, sliced roast pork loin, pickle relish, and barbecue sauce, with a frosty bottle of Dr Pepper invented in Wac, all served by “car-hops”, young boys. According to Daniel Vaughn of Texas Monthly “There are plenty of other firsts attributed to them too: the first onion ring, the first chicken-fried steak sandwich, Texas toast, neon lights. Some of those claims might be hard to prove, but they all serve as anecdotal evidence of {founders} Kirby and Jackson’s innovativeness.” The Pig Stand may have been the first restaurant chain, preceding Howard Johnson’s by a decade.

Barbecue restaurants played a role in the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his team often met in them on Chicago’s South Side and elsewhere. Brenda’s in Montgomery, AL, was a meeting place, and because they had some sort of printing machine for printing menus and flyers, probably a mimeograph machine, they printed notices and flyers for the NAACP during the bus boycott after Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a bus in 1955. A court case went all the way to the US Supreme Court and where segregation on public transit was declared unconstitutional. Brenda’s still serves barbecue, is owned by the same family, and reigns as Montgomery’s oldest BBQ joint.

In 1968 inventor Herbert Oyler of Mesquite, TX, started to build wood-fired smokers with shelves that revolved around an axle like a Ferris wheel, allowing all the meat to get even heat and smoke, and increasing capacity. He teamed with welder and fabricator Arthur Norman Bewley who lined the steel firebox with refractory, a concrete-like material that could withstand high temperatures. These innovations revolutionized restaurant pit design. Oylers are still made today by J & R Manufacturing and they are especially popular in Texas. Here’s one in use at the popular Stubbs in Austin.

In 1976 brothers Mike and B.B. Robertson started fabricating Ferris wheel style pits for restaurants with several more design innovations. Southern Pride pits eventually evolved into an impressive high tech motorized temperature and smoke controlled device that can be run by computer. They burn gas for heat and logs for smoke. Today hundreds of restaurants use them and a similar design by their competitor Ole Hickory Pits.

The history of portable barbecue

Armies travel on their stomachs and history tells us about ancient armies cooking over campfires with small gridirons and using their shields as griddles and even for making breads. Below I have attempted to show the history of portable grills and grilling. I am very grateful to grill collector and historian Ed Reilly.

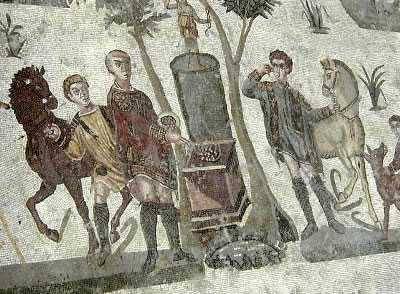

In this section of a large mosaic from a Roman hunting lodge in Sicily near the Piazza Armerina we see the hunting party stopping for lunch. The most elaborately dressed man, probably the leader of the expedition or the head of the family, is doing what Dads have always done.

When Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79, it froze the town of Pompeii for eternity. Among the artifacts found were several small grills like this one.

Above left we see an American Revolutionary War camp stove from about 1775 made of hand forced cast iron. According to the catalog at liveauctneers.com it was 10″ wide x 7″ high, weighing, 5 1/2 pounds. The bottom is open and there is a grate inside that holds the embers. Above right is another design sold at liveauctneers.com that looks a lot like a Hibachi. It is 8″ tall, 13 3/4″ wide, and 9″ deep. They could also be used to melt lead for their muskets.

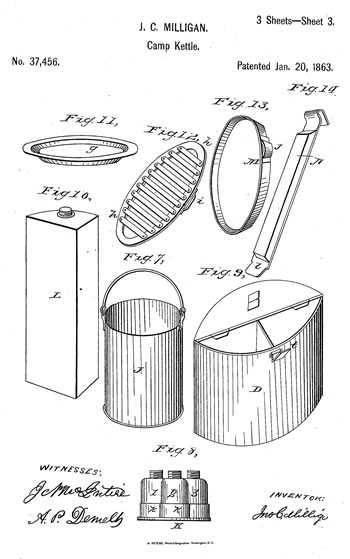

In 1863 J.C. Milligan of New Jersey patented a portable mess kettle that contained everything a soldier would need for dinner for four including a large kettle with a lid and ears that can be used to hang it over the fire, a small kettle, a gridiron for grilling, a coffee kettle, two coffee strainers, a whiskey flask, a set of four knives, forks, large and small spoons, four coffee cups, four plates, four small screwtop bottles for spices or condiments, a corkscrew, a saucepan, and a frying pan. It weighted 11 pounds and sold for a whopping $6, a lot of money in those days.

Old Sears catalogs show several designs for what were called variously lamp stoves, sad iron heaters, hobo stoves, and train or caboose stoves. Made of cast iron, they burned kerosene. “Summer Girl” was patented in 1893 by Taylor and Boggis Brothers, was 9″ tall and weighed about five pounds.

As I discuss in my article on charcoal, in the 1920s, Henry Ford, in collaboration with Thomas Edison and EB Kingsford, began making charcoal briquets commercially from wood scrap from the wood used to make cars parts in Ford’s Detroit auto plants. Ford also began selling small portable grills (above, courtesy of grill collector Ed Reilly) and promoted picnics and camping as a great use of automobiles.

Not long after, the menswear store Abercrombie & Fitch (they were very upscale in those days) becan selling a portable grill in a suitcase amde by J.M. Huntington Iron Works in La Canada, CA. It was also sold mounted to cart with a work table. This one, from Ed Reilly’s collection, is from the 1930s.

In 1948 Grant “Hasty” Hastings introduced the Hasty-Bake oven with a hood, and an adjustable height charcoal tray. They are still made today, and the modern version is one of my all-time favorite grills. It is remarkably similar. If it ain’t broke…

In the late 1940s, Winfield & Irene Alter of Tulsa, OK, began working on a kettle made of cast iron that used a rotary vent. It first came to market as Cook ‘N’ Kettle in 1947, I think. Special thanks to Ed Reilly for the photos above.

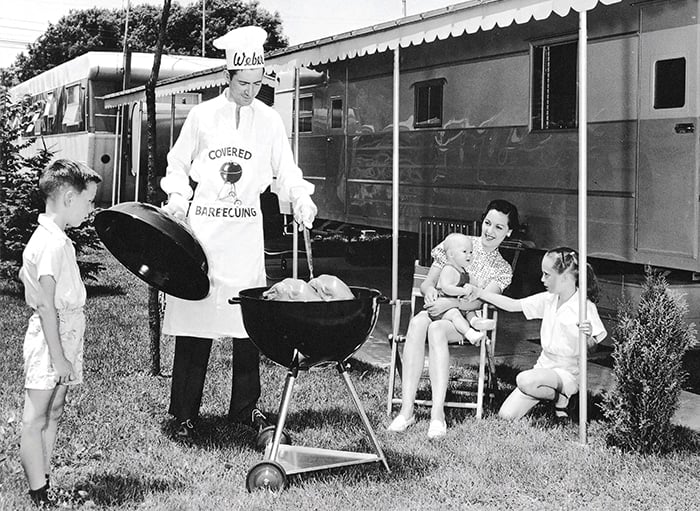

In 1951, George Stephen, Sr., was frustrated by his inability to control the heat in his backyard grill. He had the welders at the Weber Brothers Metal Works, where he worked, cut up a buoy that was to be used for Lake Michigan boating. The Weber Kettle was born and introduced in 1952 (shown at right). Weber claims that among its innovations was a tight-fitting lid and adjustable air vents that allowed the cook to control temperature, but they may have been Jack Alters’ innovations. Much of the early marketing involved touting the merits of “covered barbecuing”. The system is efficient, burning a minimum number of briquets during cooking.” Probably no other single invention has influenced the American diet more since the invention of the electric refrigerator.

Before long the Japanese Hibachi, a small portable charcoal grill without a top migrated to the US and next thing you know they had lids and handles, perfect for President Eisenhower shown here doing his guy thing on a porch at the White House, and perfect for Gidget’s beach parties.

Founded in 1853, the Columbus Iron Works in Columbus, GA, manufactured kettles and ovens, stream engines, as well as swords, pistols, and rifles for the Civil War. In 1925, the W.C. Bradley Company acquired control, and in 1953 it started selling its first Charbroil charcoal grill. Bradley has aquired numerous other manufacturers and is today one of the largest in the world. In 2006 Bradley moved all manufacturing to China, but the company headquarters are still in Columbus, and the Iron Works has been restored and turned into a convention center.

Somewhere somebody cut the top off a steel drum, dumped charcoal into the bottom, and put a metal grate on the top. His neighbor had a better idea. He cut a steel drum in half lengthwise, hinged the two parts together like a clamshell, and attached four legs. Next thing you know, in 1957 Popular Mechanics is running plans for making a barbecue from an oil barrel (shown here).

In the 1940s Chicago Combustion Corporation (now called LazyMan) began making gas grills for restaurants with lava rocks replacing charcoal and in 1959 they adapted 20 pound propane cylinders used by plumbers and began selling portable gas grills.

Also in the 1950s, Bernzomatic began selling portable gas grills. Ed Reilly thinks this one is from around 1956.

In 1960 Walter Koziol’s Modern Home Products produced consumer gas grills, the Charmglow Perfect Host, in Antioch, IL. It was round, 22.5″ across with a reflector and wind break over half the grill. A rotisserie could be mounted to the reflector. It used natural gas piped to it from the house. During the 1970s, Char-Broil became the first brand to put a liquid propane tank and a grill in one box. Gas grills soon became more popular than charcoal because they are easier to start and stop and there is less cleanup.

Meanwhile hungry Texas oil rig welders began building heavy duty steel cookers from barrels, pipes, and large propane tanks creating tubular pits that could be mounted on trailers and towed from jobsite to jobsite. Some were fitted with fireboxes on the side to hold burning logs and allow the cook to smoke meats with indirect heat, low and slow. The homemade unit at right is at the Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church Barbecue in Huntsville, TX. Some of the first retail units were made in 1973 by a fabricator named Wayne Whitworth of Pitt’s and Spitt’s in Houston. Nowadays these mobile pits have gotten complex and expensive.

On Chirstmas Eve 1963, just a month after President John Kennedy was murdered, President Lyndon Johnson and his wife Ladybird, frazzled from, as Ladybird described it, the “tornado of activity that has surrounded us” retreated to their Texas ranch. West German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard was scheduled to visit Kennedy to discuss the Soviet threat, the Berlin Wall, and other important matters. Rather than return to Washington for a formal State Dinner, LBJ invited Erhard and his entourage on down to what historians claim was the first official Presidential barbecue in history. Yes, Johnson’s first state dinner was a barbecue for 300 in Texas on December 29, 1963. Click here for more about how LBJ used barbecue to advance his policies.

In 1982 Traeger Heating in Oregon began experimenting with a furnace that would burn wood pellets made from compressed sawdust, a byproduct of the area lumber mills, and before long introduced a home heating system that they sold locally. Since furnaces sold mostly in cold months, before long they began experimenting with a grill that would burn pellets, too. Eventually they created a device with an auger to feed the pellets and a blower to help them burn. They had the field to themselves for a few years, but the idea was too good to go unimitated, and with the digital age came the electronic controller that allowed Traegers and others to create a system that had a thermostat in the cooking chamber that would tell the fan and auger when to do their thing. Today there are more than a dozen manufacturers making increasingly sophisticated machines making backyard grilling, roasting, and smoking as easy as indoors.

Who knows what’s next?

To see just about every grill or smoker that we can find in the US, along with our ratings, reviews, and recommendations, please visit our equipment reviews section.

Etymology of the word barbecue

Whether you spell it Barbecue, Barbeque, Barbaque, Barbicue, BBQ, B-B-Que, Bar-B-Q, Bar-B-Que, Bar-B-Cue, ‘Cue, ‘Que, Barbie, and just plain Q, the origins of the word barbecue, and that’s how most dictionaries spell it, are pretty clear.

There are a lot of myths surrounding the etymology of the word, so here is what we know today:

The Spanish explorer Gonzalo Fernàndez De Oviedo y ValdZÿs was the first to use the word “barbecoa” or anything like it in print in Spain in 1526 in Diccionario de la Lengua Espanola (2nd Edition) of the Real Academia Espanola. Oviedo, as historians refer to him, traveled extensively in the Caribbean and what is now Florida in the 1500s, and he was the first to describe the wooden rack above the ground used by the natives for cooking. He said it was from the Taino dialect of the Arawak American Indians. A website maintained by descendants of the Tainos says the word barbecue comes from “A poorly written translation between Spanish and English of the Taino word Barbicu”.

Was that the original word? Hard to say because several European explorers say the same word was used for a wooden rack above the ground used for sleeping and for storing food away from insects, snakes, and animals. The modern Taino dictionary makes no mention of these other uses so one has to question its accuracy.

As we know, people often have trouble pronouncing foreign words. In any case, barbacoa was the first to appear in print, and that’s the word that started going around Europe.

In 1755 Samuel Johnson, the British lexicographer, essayist, and editor included the word “barbecue” in his landmark Dictionary of the English Language.

In the early days of the automobile, restaurants in search of short names that were easy to read at highway speeds began hoisting bright signs that said “EAT”, “Cafe”, and “BBQ”.

Every other goofy explanation (see below) you have heard is wrong. Click here to read about the complete defintion of barbecue.

Fakelore: False origin stories

Some chauvinists like to think that barbecue, like jazz, is an American invention. Alas, it was not invented here. But it was perfected here.

Roasting meat over a fire has been around since naked humans lived in caves, and long before refrigeration, smoking meats was a worldwide method for preserving it. The word barbacoa is the Spanish interpretation of a word used by Taino Indians in the Caribbean first recorded in 1526.

Over the years, as etymologists sought the true origin of the word several false origin stories emerged:

The “de la barbe a la queue” story. The classic 1938 French encyclopedia of cooking, Larousse Gastronomique, naturally claims barbecue came from the French expression “de la barbe a la queue” meaning “from the beard to the tail”. It referred to a technique of impaling an animal on a roasting spit. Larousse suggests there may even be a connection to the Romanian berbec, meaning roast mutton. It is hard to find anyone in the know who thinks French or Romanian was the origin of the word.

The “Bar B.Q.” story. Robb Walsh, in his excellent book “Legends of Texas Barbecue“, reports that cookbooks in Texas tell the fanciful tale of a wealthy Texas rancher named either Bernard Quayle or perhaps Barnaby Quinn. Apparently he loved serving his friends whole sheep, hogs, and cattle roasted over open pits. His branding iron had his initials, B.Q. with a straight line beneath. It was common for ranches to be named for their brand, “Thus, the ‘Bar B.Q.’ became synonymous with fine eating – or so the story goes”. Walsh reports the myth, and a myth it surely is since the word barbecue had been in common use for many years before the hypothetical messers Quayle or Quinn.

The “Bar, Beer & Cue” story. A few folk-historians claim the word barbecue is a contraction of the name of a popular roadhouse that had pool tables. Not likely.

The buccaneer connection

The French words boucan and boucanier and various spellings of them appear in the diaries of early French and English explorers describing barbaoas.

In 1906 John Masefield, in his book “On the Spanish Main“, made the case for boucan as the name of the grill used by the Amerindians. He said “The meat to be preserved, were it ox, fish, wild boar, or human being, was then laid upon the grille. The fire underneath the grille was kept low, and fed with green sticks, and with the offal, hide, and bones of the slaughtered animal. This process was called boucanning, from an Indian word ‘boucan,’ which seems to have signified ‘dried meat’ and ‘camp-fire.’ Buccaneer, in its original sense, meant one who practised the boucan.”

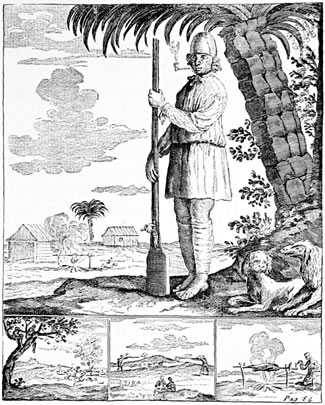

Here is an illustration from his book titled “A Buccaneer’s Slave With His Master’s Gun, A Barbecue In Right Lower Corner”.

It is interesting to note that Masefield says that “Meat thus cured kept good for several months. It was of delicate flavour, red as a rose [sounds like a smoke ring, doesn’t it?], and of a tempting smell. It could be eaten without further cookery. Sometimes the meat was cut into pieces and salted, before it was boucanned – a practice which made it keep a little longer than it would otherwise have done. Sometimes it was merely cut in strips, roughly rubbed with brine, and hung in the sun to dry into charqui, or jerked beef. The flesh of the wild hog made the most toothsome boucanned meat. It kept good a little longer than the beef, but it needed more careful treatment, as stowage in a damp lazaretto turned it bad at once [a lazaretto is a quarantine for sailors, most likely a cellar in this case]. The hunters took especial care to kill none but the choicest wild boars for sea-store. Lean boars and sows were never killed. Many hunters, it seems, confined themselves to hunting boars, leaving the beeves [beef] as unworthy quarry.”

Fans of the Pirates of the Caribbean films will appreciate this description of buccaneers from Atlantic Monthly, September 1862: “A cotton shirt hung on their shoulders, and a pair of cotton drawers struggled vainly to cover their thighs: you had to look very closely to pronounce upon the material, it was so stained with blood and fat. Their bronzed faces and thick necks were hirsute, as if overgrown with moss, tangled or crispy. Their feet were tied up in the raw hides of hogs or beeves just slaughtered, from which they also frequently extemporized drawers, cut while reeking, and left to stiffen to the shape of the legs. A heavy-stocked musket, made at Dieppe or Nantes, with a barrel four and a half feet long, and carrying sixteen balls to the pound, lay over the shoulder, a calabash full of powder, with a wax stopper, was slung behind, and a belt of crocodile’s skin, with four knives and a bayonet, went round the waist. These individuals, if the term is applicable to the phenomena in question, were buccaneers.

“The name is derived from the arrangements which the Caribs made to cook their prisoners of war. After being dismembered, their pieces were placed upon wooden gridirons, which were called in Carib, barbacoa. It will please our Southern brethren to recognize a congenial origin for their favorite barbecue. The place where these grilling hurdles were set up was called boucan, and the method of roasting and smoking, boucaner. The buccaneers were men of many nations, who hunted the wild cattle, which had increased prodigiously from the original Spanish stock; after taking off the hide, they served the flesh as the Caribs served their captives. There appears to have been a division of employment among them; for some hunted beeves [beefs or cattle] merely for the hide, and others hunted the wild hogs to salt and sell their flesh.”

Note that Masefield, the Atlantic, and many others before them, described the natives boucanning and barbecuing humans. Warnes and others question the veracity of claims of cannibalism, saying they were likely invented by Europeans to justify their own violence and rationalize their attempts to convert the “barbarians” but, in my readings of original diaries, I have seen so many descriptions of barbecuing and grilling of humans, usually enemies or criminals, that it seems that the practice was real.

Stories intersect here in the most interesting manner. Buccaneers plyed both the Caribbean and the Pacific coast from Mexico to South America. Off the coast of present day Colombia and Ecuador was especially happy hunting in the late 1600s. According to historian Kris E. Lane “The Spanish knew the region as the Barbacoas, having brought from the Caribbean the Ta’no word for the stilt houses favored by its native population”.

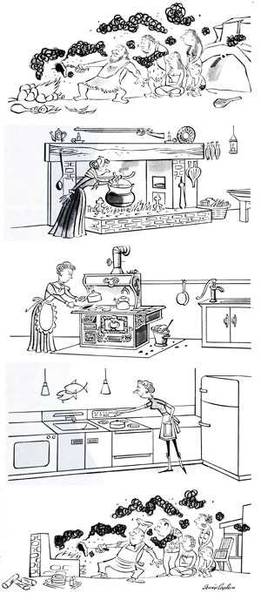

How it all began!

Yes, that’s the title of this cartoon from Collier’s magazine, circa 1954.

Foods native to the New World

Until Columbus and other explorers, according to Raymond Sokolov’s book Why We Eat What We Eat, there were no tomatoes for Italian pasta sauce, there were no hot chile peppers for Chinese Szechuan cuisine,no Belgian chocolates, no potatoes in Ireland, and the Tacos the Mexican Aztecs ate were filled with insects instead of beef.

According to Sam Brookes, Heritage Program Manager of the National Forests in Mississippi, Europeans discovered these new foods on their explorations:

- Corn (hundreds of varieties)

- Beans (hundreds of varieties)

- Squash and Pumpkins

- Tomatoes

- Chile peppers

- Wild rice

- White potatoes (numerous varieties)

- Sweet potatoes

- Peanuts

- Plums

- Strawberries

- Persimmons

- Pineapple

- Raspberries

- Blueberries

- Blackberries

- Cranberries

- Avocados

- Black Walnuts, Hickories, Chestnuts, Pecans, Filberts, and Brazil Nuts

- Chocolate

- Vanilla

- Sassafras

- Maple sugar

- Turkeys

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators