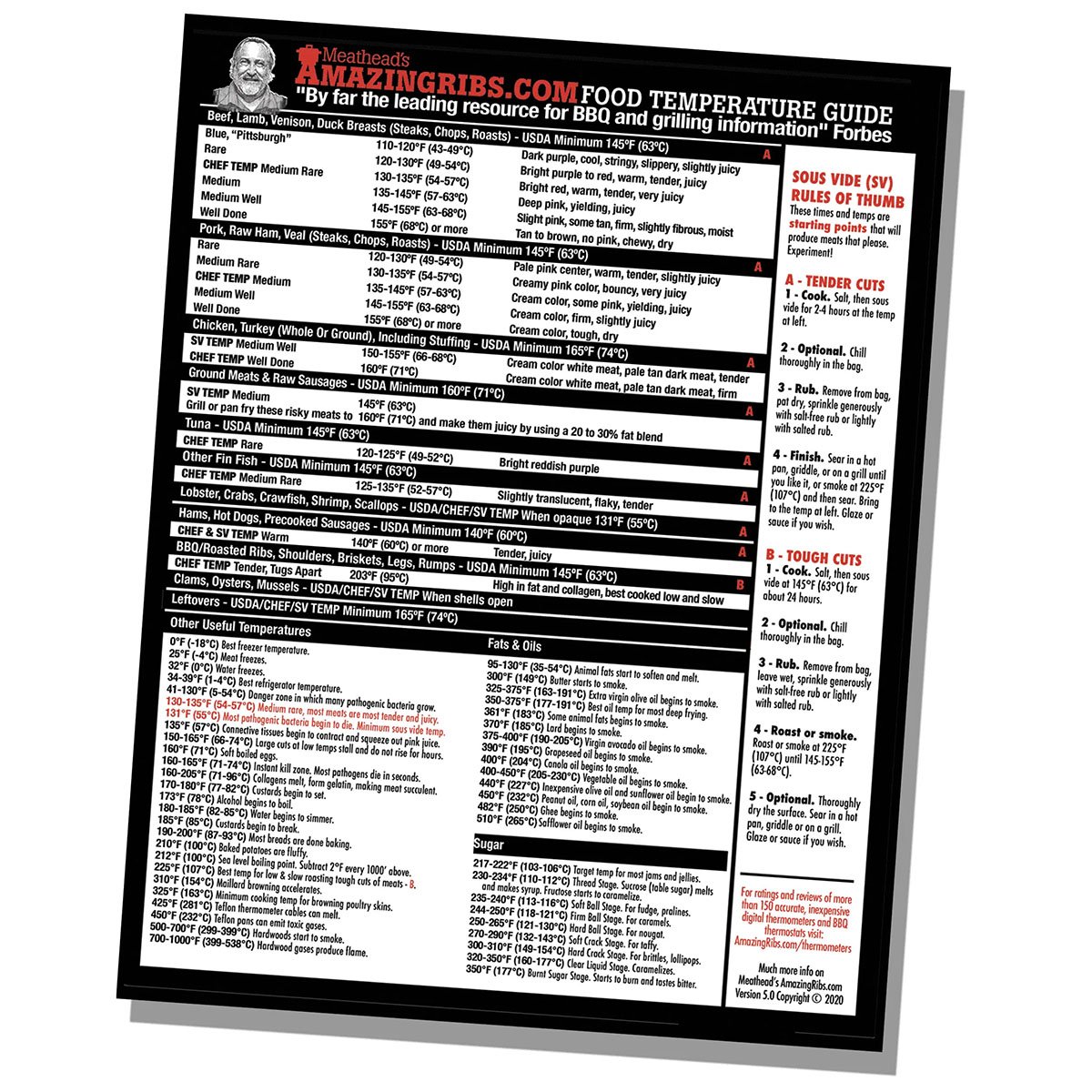

| Click here to order this 8 1/2 x 11-inch comprehensive food temperature safety magnet It won the National BBQ Association’s new product of the year award when it was introduced and it has been improved annually since. It contains more than 80 benchmark temperatures for meats (both USDA recommended temps, as well as the temps chefs, recommend), fats and oils, sugars, sous vide, freezer, and fridge temps, eggs, collagens, wood combustion, breads, and more. Although it is not certified as all-weather, we have tested it outdoors in Chicago weather and it has not delaminated in three years, but there is minor fading. |

Click to order our comprehensive Food Temperature Guide

I want my meat tender, juicy, and flavorful. I also want it safe. The internal temperature of meat controls all of these things and understanding what temp is optimum and safe is at the core of good cooking.

Nobody knows how many millions of dollars were wasted on overcooked food, but far more importantly, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that in 2011 roughly one in six Americans got sick from food-borne illnesses, about 128,000 were hospitalized, and 3,000 Americans died, about the same number who died in the attacks in 2001 or Pearl Harbor in 1941. The difference: Many were children.

The fever, sweats, and runs that most people call “stomach flu” are no such thing. They are almost always a food-borne illness caused by bacteria such as Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia-coli (E-coli), Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus. True stomach flu is a viral infection caused by different viruses than the Influenza viruses and occurs much less frequently. Chances are that if you think you had stomach flu, you really had a food borne illness that probably could have been prevented by proper cooking.

Cooking without a good digital thermometer and a good temperature guide (like the one on this page) is like driving without a speedometer.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) publishes recommended meat temperatures. It is an admirable effort, but it is oversimplified and slightly misleading in order to make it easier for the public to remember. Even so, everyone reprints USDA numbers because they are afraid of being sued or because they just don’t understand the issues.

No professional chef would use the USDA guide for everything. For example, USDA recommends a minimum temp of steak to be 145°F, which is classified by chefs as “medium” and by many steak lovers as overcooked. “Medium rare”, 130°F to 135°F, is the temp range at which steaks are at their most tender, juicy, and flavorful. If restaurants cooked steaks to 145°F minimum, every steakhouse in the nation would go out of business.

In fact, USDA has changed the numbers several times. As recently as 2011 they reduced the temp for pork. Clearly the pork lobby has more clout than the beef lobby.

On the other hand, USDA recommendations for ground meats and poultry should be adhered to closely. The sad fact is that the risk of contaminated chicken, turkey, and ground meat is too high to take chances, especially with the young, old, or immune-compromised.

But it is not just temp!

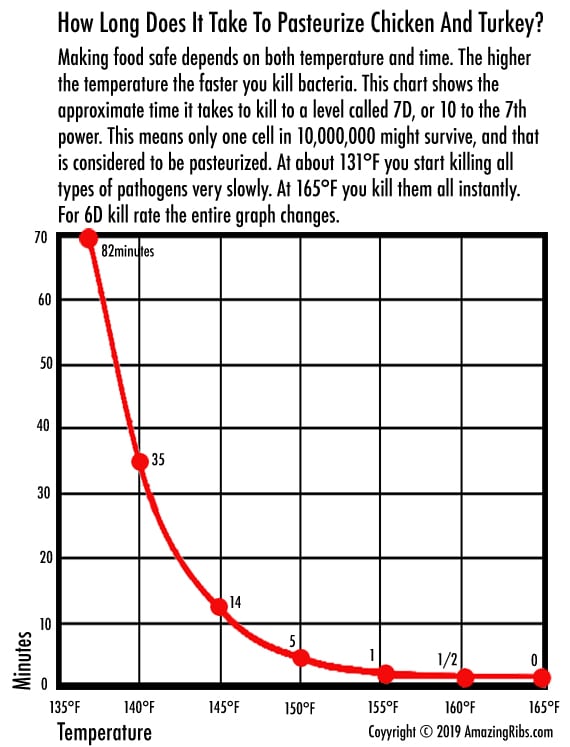

To pasteurize meat, USDA and my chart give us minimum temperatures, like 165°F for poultry and 145°F for fish. But if you dig into the data by USDA scientists, you learn that this is a distillation of the facts designed to make things easy for the public.

Pasteurization of meat is not just a matter of temperature. It is a measure of temperature, time, and the desired kill rate taken together.

Here’s the whole story: It is almost impossible to sterilize meat, meaning all microbes are dead and still have it palatable. So we settle for pasteurization, which means that so few bugs are left that the chances of getting sick are so minute that we shouldn’t worry.

The USDA standard for pasteurization of meat is a kill rate of 7D or 10 to the 7th power or one cell in 10,000,000. Let’s say there are 1,000 pathogenic cells on a raw 10-ounce burger, a large burger, and that would be a lot more than you would normally find on a badly contaminated burger. A 7D kill rate means that there might be one cell surviving on 10,000 burgers. One cell is not likely to make anybody sick, it normally takes a lot more than that to take out a large animal like a human, so the USDA has decided that a 7D kill rate is pretty darn safe. Incidentally, the EU considers 6D safe.

Pathogens start keeling over at about 130°F. But at that temp, it takes at least two hours to kill them to 7D. The time gets lower as the temperature goes higher. So beef at 140°F degrees will get to a 7D kill rate in just 12 minutes, while at 160°F degrees, pathogens are destroyed in just 7.3 seconds, hence the USDA guidelines for the consumer. They made the decision to publish a number that produces “instant kill”, or in this case, “instant” means 7.3 seconds at 160°F. But keep in mind, that the meat has been slowly warming to 160°F, killing pathogens all along the way.

But you can feel safe eating a pink burger by holding it at 135°F for 37 minutes, according to the USDA Food Safety Inspection Service technical documents.

This is the secret behind sous vide cooking. Sous vide machines are precisely controlled warm water baths usually set for 130°F and above. Food is placed in vacuum-sealed bags and submerged in the water. It can remain there for hours and never go higher than 130°F. When it is time to serve, you just sear it to get those good dark brown flavors. In fact, if you are willing to accept a 6D kill rate, 1 cell in 1,000 big burgers, a pretty darn safe level, the time goes down even more.

Minimum Pasteurization Times For Selected Meat Temperatures*

| Chicken & Turkey With 12% Fat | |

|---|---|

| 136°F (57.8°C) | 82 minutes |

| 140 (60.0) | 35 minutes |

| 145 (62.8) | 14 minutes |

| 150 (65.6) | 5 minutes |

| 152 (66.7) | 3 minutes |

| 154 (67.8) | 2 minutes |

| 156 (68.9) | 1 minutes |

| 158 (70.0) | 41 seconds |

| 160 (71.1) | 27 seconds |

| 162 (72.2) | 18 seconds |

| 164 (73.3) | 12 seconds |

| 166 (74.4) | 0 seconds |

| Beef, Lamb, & Pork | |

| 130 (54.4) | 121 minutes |

| 135 (57.2) | 37 minutes |

| 140 (60.0) | 12 minutes |

| 145 (62.8) | 4 minutes |

| 150 (65.6) | 72 seconds |

| 155 (68.3) | 23 seconds |

| 158 (70.0) | 0 seconds |

| * For a 7D reduction in pathogens, rounded up to the nearest whole number. | |

| Source: USDA Food Safety Inspection Service | |

Here’s a graph of the poultry data:

Now before you go off cooking chicken to only 145°F for 14 minutes, beware that you must have a precision thermometer and you should probably round up to 20 minutes or more. And there is still a risk. If the concentration of pathogens is exceptionally high in your meat because it sat too long at room temp, or if for some reason the bugs got pushed down below the surface, or there was a really dense clump of bad guys, well, in the words of Dirty Harry, “you’ve gotta ask yourself a question: Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya, punk?”

Our Comprehensive Food Temperature Guide

The AmazingRibs.com Food Temperature Magnet shown at the top of this page has both USDA-recommended minimum temps and the temps that Chefs use (they are not always the same). It contains 82 food and other temperature benchmarks such as when fats melt, when collagen melts, oil smoke points, sugar stages, and more. This nifty refrigerator magnet won first prize as “Best New Tool or Accessory” at the National Barbecue Association conference in February 2012 and it has gone through several upgrades since then. The 8.5″ x 11″ glossy refrigerator magnet sells for $9.95 on Amazon. It is free if you join our Pitmaster Club. Beware of imitations and knockoffs.

We will have it available on Amazon soon.

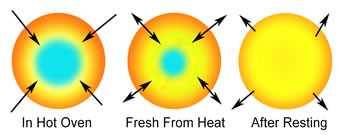

Carryover. Most cooking is the process of hot air warming the outside of the food, and the outside of the food warming the inside. When meat comes out of the oven/grill/smoker, the heat contained on the outside of the meat continues to warm the meat further in, so the temp in the center continues to rise. This is called carryover cooking.

Carryover has more of an impact on thick cuts than thin cuts because thin cuts cool more quickly and there is a lot of surface area compared to the total mass. In other words, a 1″ steak will not continue to warm more than a degree or two after you remove it because the surface to meat ratio is large and most of the heat will bleed off into the air and the plate. But a prime rib roast that is 4 to 6″ thick will have significant carryover because the meat has much greater mass and the center is better insulated.

Carryover also is impacted by the cooking temp. The hotter you cook, the more energy you are packing into the outer layers, so the carryover will be greater than if you cook at a lower temp.

As a rule of thumb, small pieces of meat like steaks, chops, and chicken will not continue to cook much after you take them off the heat, certainly no more than 3°F. But large thick roasts of beef, lamb, veal, pork loin, or even large turkey breasts should come out of the heat at 5°F less than the desired temp and they will rise about 5°F in the time you move it indoors and start carving or serving. If you are cooking at high temps, carryover can be up to 10°F. If you are cooking at low temps, it might not go up the full 5°F. But 5°F is a good rule of thumb for most roasts.

Medium rare is the best temp for beef, lamb, venison steaks, roasts, and duck breasts. Food scientists have the equipment to measure tenderness and juiciness. They apply force to the surface until it sheers, and measure how much pressure is needed. Medium rare wins. As the temperature rises above 140°F proteins start to bunch up, get chewy, and squeeze out juices. So if you order meat medium or well done, don’t complain if it is not juicy or if it is tough. That’s what you asked for. Click here for more on the higher the meat temp, the tougher it gets.

Resting meat. All the cookbooks say that you must rest your meat for at least five to 15 minutes after cooking to make it juicier. This has been disproven. Serve your meat hot, but be aware that if you wait a while, the heat built up in the meat will continue to cook from carryover it and it could be overcooked by the time you serve it.

Pork steaks and pork roasts. Once upon a time, it was easy to get sick from the parasite trichinosis (trick-a-NO-sis) from undercooked pork. Today trichinosis has, for all practical purposes, been eradicated in developed countries. The annual average is now fewer than a dozen cases per year in the US, most associated with eating undercooked wild game such as bear. Trich in pork has disappeared because of improved farming and processing methods as well as public awareness of the importance of proper cooking. Trichinosis is killed at 138°F and the new minimum recommended by USDA is 145°F.

Pork and beef ribs, pork shoulders, and beef brisket. These cuts are safe at 145°F, but we deliberately cook these meats up to 203°F, well past well done, in order to melt the connective tissues that are rife in these tough cuts. That may seem extreme, but I’m here to tell you that low slow long cooking produces amazing results.

Poultry. Researchers tell us that a significant percentage of chickens and turkeys have salmonella in their juices. I find it helpful to treat raw chicken and turkey like kryptonite. USDA says to serve poultry at 165°F and most chefs agree and remove it at no lower than 160°F allowing for 5°F carryover. Push the thermometer probe through the breast to the ribs at its thickest part and back it out slowly reading the temp along the way. At 165°F white meat is still moist. Much higher and you’ll be eating cardboard. The transition happens rapidly. Thighs and drums have a bit more myoglobin and fat and they can take a bit more heat. They seem to taste best in the 165°F to 170°F range. The old saw that when the juices run clear chicken is safe just isn’t true anymore.

Ground meat, burgers, and sausage. The USDA recommended temp is 160°F and it should be adhered to closely. Alas, 160°F is also well done. The risk of contamination from a pathogenic strain of E. coli is too great to mess around undercooking ground meat. Why is ground meat different than whole muscle meat? Prior to slaughter cattle are usually kept in crowded pens. Fecal matter can easily get on their hides. During butchering of the carcass knives cutting the hide can contaminate the meat.

Also, the intestines, full of fecal matter, can easily be cut open by mistake and spill onto the meat, floor, knives, and gloves. A little E. coli on a steak is not a problem because they remain on the surface and they are killed rapidly by cooking. But when meat is ground, the contamination on the surface is mixed into the center. If it is not cooked to 160°F, it can find its way into your gut and cause discomfort, illness, or even death. So ground meat must be cooked to a higher temp than whole muscle meat. Don’t screw around. The risk is too high, especially for young and elderly people at your table.

There are tricks for making safe burgers that are medium-rare or pink in the center and I describe them on my page on food safety.

Fish. USDA recommends serving it at 145°F because fish are susceptible to parasites, often from the droppings of warm-blooded animals such as seals. It is easy to overcook fish, so be vigilant.

Precooked ham. Serve at 140°F. This stuff is cured with salt and pre-cooked, so you are really just warming it. No need to dry it out by overcooking. USDA agrees.

Eggs. Eggs pose a significant safety risk. Remember the gigantic egg recall and related illnesses in 2010? Salmonella enteritidis is widespread among hens nowadays and it infects the ovaries of otherwise healthy appearing animals. In the ovaries, it infects eggs before the shells are formed. It is estimated that one in 20,000 eggs is contaminated with Salmonella in the US, and in the Northeast US it may be one in 10,000.

The CDC estimates that one in 50 consumers eats a contaminated egg each year because large batches of eggs are cracked and blended together by food processors and restaurants. Salmonella growth is inhibited by refrigeration, so eggs should not be kept at room temp. Cooking eggs to 160°F, so their yolks are firm, makes them safe. You should use a thermometer on egg-based casseroles.

If you like runny yolks or dishes made with lightly cooked eggs such as soft boiled eggs, pasta carbonara, egg nog, Caesar salad dressing, custards, or bearnaise and hollandaise sauces, it is strongly recommended that you use pasteurized eggs. They are perfectly safe, they taste great, and they are now widely available.

Vegetables and other foods. The plain fact is that anything eaten raw has higher risk than cooked. Heat kills. That’s why there have been so many outbreaks in spinach and other greens. They are exposed to pathogens on the farm. They grow close to the ground where rabbits, deer, and mice roam. What is the most dangerous food in the world? Click here to read the surprising answer.

Water temps. At sea level, water starts a rolling boil at 212°F. It starts to simmer with tiny bubbles and visible steam at about 180°F and the bubbles get larger as the temperature rises. The bubbles are water that has been heated to boiling temperature by contact with the metal bottom of the pan which is hotter than the rest of the water because the bottom is in contact with the heat. To poach eggs and meats, you want the water at least 160°F to be safe, and under 180°F. The boiling point goes down about 2°F for every 1,000 feet above sea level because the weight of the air column on the surface of the water, is lower than at sea level.

Bread. For blooming yeast, use water in the 105 to 115°F range. Bake lean doughs to 190 to 200°F. Bake rich doughs to 180°F.

Butter. Butter begins to get soft enough for a recipe that calls for softened butter at about 65°F and it melts at about 85°F.

Stages of Sugar Syrup in Candy Making. As sugar heats, it melts, the water in its chemistry boils off and it goes through stages of concentration that candy makers need to know. Click here for more on sugars and sweeteners, and a table of the different stages of sugar melting.

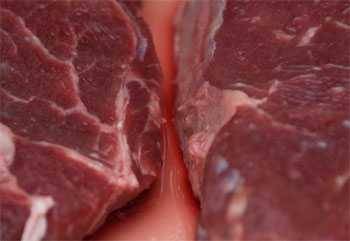

Beef cooked to different temperatures

In the photos above, you can see how the color of beef changes as the interior temp increases, and how moisture diminishes.

But beware, you cannot tell a meat’s temp by its color. There are other factors that influence color such the cut of meat, the age of the animal, gases in the cooker from combustion or other foods, handling in the production and distribution process, the diet of the animal, fat content, etc.

If you cut into a steak to look at the color, you might be surprised to discover that the color is significantly different at the dinner table after the meat has been exposed to oxygen. Even the type of light you have by the grill can mislead you. There is one and only one way to tell if meat is cooked to the proper temp and if it is safe: With a digital thermometer.

Chicken breasts cooked to different temperatures

As the meat warms you can see the color change, moisture diminishes, and texture gets more stringy making it more difficult to cut smoothly.

Pork loin cooked to different temperatures

Loin (not to be confused with tenderloin) is a long muscle that runs along the spine. It is the same cut as the beef ribeye. The center tube is the longissimus, and it often has a smallcurved muscle wrapped around it called the spinalis, which is often much darker. Here are some slices from the same loin with a bit of the spinalis showing.

Mythbusting: The red stuff is blood

It’s not blood! It is a protein from within the muscle fibers called myoglobin mixed with water from within the fibers.

If it was blood, it would turn black and coagulate on your plate! You’ve seen this occasionally when a bit of blood left in the marrow of a bone leaks out when you cook. It gets hard and black. But the bright red liquid in your plate is thin, fluid, and flavorful. That’s because it is myoglobin, not blood.

In Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry by David L. Nelson and Michael M. Cox, 4th Edition, 2005, it says “Myoglobin is a relatively small oxygen-binding protein of muscle cells. It functions both to store oxygen and to facilitate oxygen diffusion in rapidly contracting muscle tissue.” They go on to explain that myoglobin contains the heme portion of iron that gives muscle its red color, just as it gives hemoglobin in blood its red color. Apparently the only time myoglobin is found in the bloodstream is after a muscle injury.

Let’s just call it “juice” from now on, OK?

Mythbusting: Follow recipe cooking times carefully

Many cookbooks tell you to cook some cuts for X minutes per pound. You’ve got to be careful with these rules of thumb because they are for “typical” cuts. Thickness is the really crucial factor, not the weight. Thickness determines how long it takes heat to be transmitted to the center of the meat. Other factors that can influence cooking time are the temperature of the meat before you start cooking, the type of cooker, the amount of bone, how many times you open the cooker, the humidity in the cooker, how much other food is in the cooker, and how much of a fat cover there is since fat cooks at a different rate. Again, there is no substitute for a good thermometer.

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators