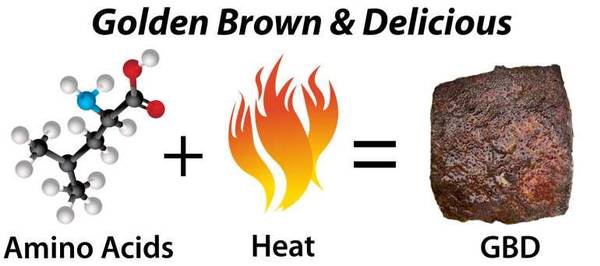

When heat is applied to food, the chemicals in the food change. A lot. Heat is powerful energy. Some changes are obvious, some subtle, some invisible. The most important of these changes are the Maillard reaction and caramelization. Together they make miracles. Together they make GBD: Golden Brown and Delicious. Here’s the highly technical formula:

Heat + Sugars + Amino Acids = GBD (Many different large scrumptious brown molecules)

Maillard reaction

The Maillard reaction is one of the great miracles of cooking, named after the French scientist Louis-Camille Maillard, who studied the browning of foods in the early 1900s. As the surface of foods warm in dry heat (and frying is considered dry heat), the chemistry of foods react, scores of new compounds form, the surface starts to brown and get crunchy, and it develops a richness and depth of flavor and texture that cannot be produced by wet cooking methods like steaming or braising. To be more specific, there is a reaction between amino acids in proteins and reducing sugars (fructose and glucose, but not sucrose) in meats. In baked goods, wheat proteins (like gluten) and added or naturally occurring sugars react to the heat and produce the flavorful brown.

Because of the Maillard reaction, steaks develop their richly flavorful mahogany surface, roasts build a bark, loaves of bread are swaddled in crusts, slices of bread turn golden in the toaster, a roux goes from pasty to golden, fried potatoes put on a golden crunchy coat, dark beer gets its darkly mysterious flavor, and boring beans are transformed into coffee and chocolate. And Gus’s fried chicken in Memphis, shown here. The reaction is even part of human aging when proteins and sugars get together in our bodies. The Maillard reaction begins at low temps, but really kicks in after 300°F. Like many chemical reactions, time can be traded against temperature. Twelve hours at 225°F will brown meat nearly as deeply as 15 minutes on the grill, but the exact mixture of flavor compounds will differ. Good thing, too. Wouldn’t it be boring if all food tasted the same, no matter how it was cooked?

The Strecker Reaction

In the Strecker Reaction one of the compounds created by the Maillard reaction called an α-dicarbonyl compound combines with the amino acid methionine, common in meat cells, to make yet another flavor compound, methional. Methional is one of the main fragrances from cooked meat.

Caramelization

Go into your kitchen and pour half a cup of sugar into a sauce pan and turn the heat to medium. It will begin to liquefy. Gently move a wooden spoon through the sugar until it all melts (beware, liquid sugar is very hot and a tiny bit on your hand will make you scream aloud, so wear gloves). Stand there and stir every 20 seconds or so. Keep stirring for about five minutes and turn the heat to low as it really starts melting. The energy will take a white odorless crystal and break it into thousands, yes thousands, of new molecules, fill the house with seductive, sweet, buttery aromas, and turn the white mass into a seething golden syrup. Then it will turn amber, then copper, then brown, then mahogany, then licorice. The process creates a rich, complex, caramel or butterscotch flavor. That is caramelization and why we love it.

In technical terms, caramelization is the controlled oxidation or burning of sugar in the presence of heat. The process breaks down the large sugar molecules, boils off the water, and recombines the remaining atoms into rich new flavors. Unlike the Maillard reaction, no proteins, amino acids, enzymes, or alkaline conditions are needed.

Different sugars caramelize at different temps, and the exact temp can vary depending on how pure the sugar is. Caramelization of fructose (fruit sugar) begins at about 230°F, and most other common sugars such as sucrose, or table sugar, start to caramelize at about 320°F. Boiling sweet sauces or exposing them to flame can create a caramel undertone, and browning sweet vegetables like onion or corn, can add depth to their flavor. Think grilled onions.

Barbecue sauces usually develop interesting new flavors when caramelized which is why they are hard to judge when they are straight out of the bottle. Because honey is mostly fructose, it makes a good addition to barbecue sauces so it can caramelize at the lower temperatures we like for low and slow barbecue. But it can also burn easily, a real possibility if you to sizzle on your sauce at a high heat after a low and slow cook as I recommend in my recipe for Last Meal Ribs. That’s why you need to be careful when tempted to substitute one sugar for another in tried-and-true rub and sauce recipes.

The AmazingRibs.com science advisor Prof. Greg Blonder did an interesting demonstration of the concepts. He placed a half a bagel, a bowl of table sugar (sucrose), and a bowl of grape juice in a 225°F oven for several hours. The bagel turned brown from the Maillard reaction because it contains sugar and protein, the fructose in the grape juice caramelized, but the table sugar remained snowy white.

So what does this mean to a barbecue cook? Says the scientist: “A glaze or sauce sweetened with table sugar won’t caramelize at the recommended low and slow temp of 225°F. But it will contribute to the Maillard reaction within the meat and the bark. ” Bark is the dark crust prized by pitmasters.

The lesson is that you want to pick your sweeteners and when you apply them carefully. If you want a nice dark surface on grilled meats, and all the flavor that comes with it, a light sprinkling of sugar before cooking, and allowing it to dissolve in the meat juices, can do wonders. If you apply a sweet sauce too early in the cook, it can mean a black disaster. If you are at low temps and you use the right sugar, you can amp the taste up a notch.

When you see TV chefs talking about the nice caramelization on a seared piece of meat, they are mostly wrong. It is mostly maillard reaction. Yes, meat has trace amounts of sugars because when an animal digests, it converts carbs in its feed into sugars for energy to be burned by its muscles, but there are a lot more proteins and amino acids than sugars and carbs.

Lipid oxidation

While all this is going on, fats (a.k.a. lipids) combine with oxygen forming other attractive aromas. When lipid oxidation occurs rapidly during cooking the result is positive. If it occurs slowly over weeks and months in the freezer, for example, the pungent smell, called rancidity, can be quite unpleasant. Interestingly, in some cultures, rancid fat can be desirable as in many aged sausages in Europe, aged cheeses, and even aged meats in Asia.

Brown good. Black bad.

The goal is a that range of colors from golden amber to whiskey brown as dark as possible but not black. That’s the fat side of a smoked culotte cut from a beef sirloin. Brown is complex lyric poetry. Black is carbon. You like black? Go eat a briquet.

Be careful with the sugar. Some rubs have lots of sugar, like Meathead’s Memphis Dust. It must be cooked low and slow or it will blacken. I see a lot of Southern style barbecue that is black and, although it may not taste carbonized, it usually doesn’t have richness and depth. On the other hand, of you are cooking at 325°F, a pinch of sugar can aid with browning and start caramelizing.

Keep things dry. Pat it dry with paper towels before cooking. If the surface of your food is wet with wash water, meat juices from the package, or marinade, the surface will steam and not brown. That’s a major reason I am not a fan of marinades or basting. They prevent browning and they never penetrate very deep. They are really a surface treatment, like a sauce, and sauces are best reserved until the last minute after the surface is done.

Keep things oiled. Oil conducts heat better than air, and it fills in the tiny air gaps between the bottom of a piece of meat and hot grill grates. Give the food a coat of oil and you can practically fry the surface, and the oil keeps food from sticking. Much of it will drip off, so don’t be diet conscious here.

Keep things at the right temp. To get a good brown surface, you need one of two things: (1) A hot direct radiant heat source from below, or (2) long low cooking times. Master your cooker. Learn how to hit 225°F, 325°F, and Warp 10. Preheat the cooker properly. But don’t go crazy, there are times when you want to work on the surface and there are times when you want to work on the interior. This concept is discussed in detail in my article on cooking temps and the reverse sear.

Turn frequently. I know you’ve been told to turn minimally. This is yet another husband’s tale disproven by science. When you do that the heat builds up and passes into the interior of the food. By turning you are in a sense rotissering, letting the surface heat, brown, and then flip and cool. Flip, add more brown, then cool so you can flip again and add more. Click here for a detailed discussion on the of flipping.

Give ’em space. If you are using a griddle or frying in a pan, don’t crowd the pan. Leave plenty of space between food chunks so steam can escape or the temp will go down and you won’t get GBD.

Add a pinch of sugar. When you make your spice rubs, add a pinch of sugar for foods to be cooked low and slow. If you are cooking hot and fast, skip the sugar it will burn. And no, sugar substitutes will not work. Wrong chemistry.

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators