The BBQ Stall. The Zone. The Plateau. It has many names and has freaked out many a backyard pitmaster. I know because they email me right in the middle of their cook. Panicky.

You get a big hunk-o-meat, like a pork shoulder or a beef brisket, two of the best meats for low and slow smoke roasting, and you put it on the smoker with dreams of succulent meat dancing in your head. You insert your fancy new digital thermometer probe, stabilize the cooker at about 225°F, and go cut the lawn. Then you take a nap.

The temp rises steadily for a couple of hours and then, to your chagrin, it stops. It stays there. It stalls for hours and barely rises a notch. Sometimes it even drops a few degrees. You check the batteries in your meat thermometer. You tap on the smoker thermometer like Jack Lemmon in the China Syndrome. Meanwhile, the guests are arriving, and the meat is nowhere near the 203°F mark at which it is most tender and luscious. Your mate is giving you that look.

Sterling Ball of BigPoppaSmokers.com, a major retailer of grills and smokers and a successful competition cook says that “no matter what I tell customers when the stall hits them, they are horrified. It seems to last forever. They crank up the heat. They bring the meat indoors and put it in the oven. They call me at all hours.”

What the heck is happening? We’ll explore it in-depth below!

Cheat sheet for this article

Don’t care about the details? Then let’s cut to the chase. Large chunks of meat, when cooked at low temps, hit a point at about 150°F when the interior temp stops rising. For hours. The exact temp depends on many variables, especially airflow through the cooker. Electric smokers have no combustion, so there is little airflow, and the stall is minimal. The stall is longer in drafty wood smokers.

This “stall” is caused by moisture evaporating from the surface and cooling the meat just like sweat cools you on a hot day. It has nothing to do with fat or collagen. If you wrap the meat in foil, the humidity in the foil is close to 100%, but there is no evaporative cooling, so this method, called the Texas Crutch allows you to power through the stall.

What causes the stall

Many pitmasters have long believed that the stall was caused by a protein called collagen in the meat combining with water and converting to flavorful and smooth gelatin. Called a “phase change,” the conversion of collagen starts happening at about 160°F, right about the same time as the stall. Seems logical. But, as our original research has discovered, it is an old husband’s tale.

Others have speculated that the stall was the fat rendering, the process of lipids turning liquid, another phase change. Another myth.

Still others thought it was caused by protein denaturing, the process of long-chain molecules breaking apart. (For more about these processes, see my article on meat science). Another myth.

Yes, all of these complex processes use energy in the form of heat. But the question is can they stop the temperature from rising for hours?

Turns out, they cannot. As our research has discovered, the stall is much simpler, and there is a cure for it.

Prof. Blonder to the rescue

Prof. Greg Blonder of Boston University is a physicist, engineer, food scientist, former Chief Technical Advisor at AT&T’s legendary Bell Labs, and the AmazingRibs.com science advisor and mythbuster. At our request, in 2016, he set out to figure out what causes the stall. His answer: “The stall is evaporative cooling.”

It’s that simple. The meat is sweating, and the moisture evaporates and cools the meat just like sweat cools you after cutting the lawn on a hot day. Here’s how he proved it.

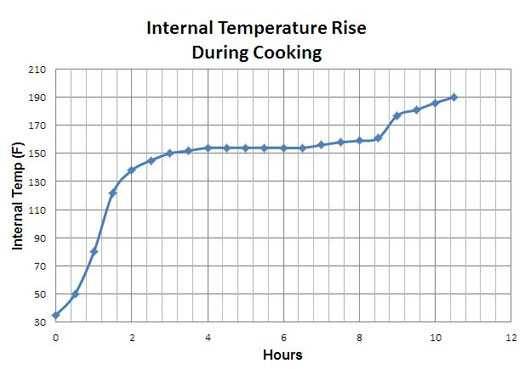

Prof. Blonder charted a brisket cooking on a thermostatically controlled smoker. In his test (see the graph above), you can see that the stall starts after about two to three hours of cooking when the internal temp of the meat hits about 150°F. The stall lasts for about six hours before the temp begins rising again. Your graph may vary depending on the type of meat you use, its size, and your cooker, but the curve should be similar.

Next, he did some calculations and determined that the amount of energy required to melt the collagen would be far less than that consumed during the stall. A pork shoulder is about 65% water, 15% fat, 8% protein, and 2% sugars and minerals. About one-fourth of the protein, about 2% of the meat, is collagen.

The science behind it

Here’s the logic: The fuel in your cooker (oxygen plus charcoal, gas, or pellets) burns and produces energy that enters the cooking chamber in the form of heat. Some of it escapes through the metal sides and some goes up the chimney. But some is absorbed by the cold meat. When the meat heats, some of the energy is used by raising the temp of the entire hunk, some of it is used in changing the chemistry and physical structure of the molecules in the meat, and some is used to melt fat and evaporate moisture. Pork shoulders and brisket have relatively high connective tissue content.

These connective tissues form a sheath around muscle cells that connect them to each other. They enclose bunches of muscles forming fibers, encase fibers into whole muscles, and connect muscles to bone in the form of tendons and ligaments. Some are made of really tough stuff called elastin. But some connective tissues are made of collagen. After some calculations, the math didn’t add up. There’s just not enough collagen to suck up all the energy necessary to prevent the meat from increasing in temp. So it had to be something else, and Blonder’s final test proved it.

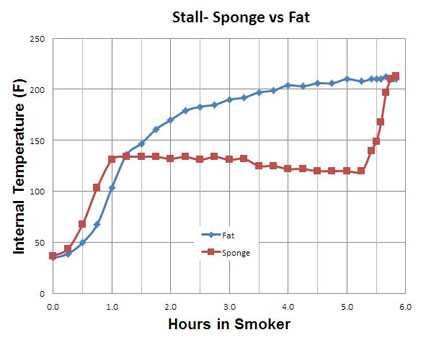

Hypothesizing that the stall might be evaporative cooling, but still wondering if it may be fat melting, Blonder took a lump of pure beef fat from the fridge, inserted a thermometer probe, and placed it in a thermostatically controlled smoker. He also soaked a large cellulose sponge in water, shook it out, inserted a probe and placed it next to the fat. Then he set the smoker for 225°F.

Results

The results are pretty clear. In the graph, the sponge is the red line and the fat is the blue line. The fat did not have a stall at all. It slowly and steadily heated on a nice gradual curve. But brother, did the sponge ever stall. It climbed at about the same rate as the fat for the first hour to about 140°F, and then it put on the brakes. In fact, it even went down in temp! When it dried out after more than 4 hours, it took off again.

|  |

The conclusion was inescapable: “Since there was a deep, glistening pool of melted fat in the smoker, the rendering fat hypothesis is busted. The barbecue stall is a simple consequence of evaporative cooling by the meat’s own moisture slowly released over hours from within its pores and cells. As the temperature of cold meat rises, the evaporation rate increases until the cooling effect balances the heat input. Then it stalls, until the last drop of available moisture on the surface is gone.” This process also explains the formation of bark, the dried jerky-like crispy surface imbued with spices that barbecue lovers crave. Click here to learn more about bark.

The stall may begin at an internal temp that’s anywhere between 150 and 170°F, depending on the particular piece of meat (size, shape, surface texture, moisture content, injection, and/or rub) and the cooker (gas, charcoal, logs, pellets, airflow, water pan and humidity), not to mention the accuracy of your thermometer. Humidity is a major factor. The measured temp of the stall also varies because the phenomenon is caused by actions on the meat’s surface yet your thermometer is testing internal temps well beneath the surface.

What temperatures cause the bbq stall?

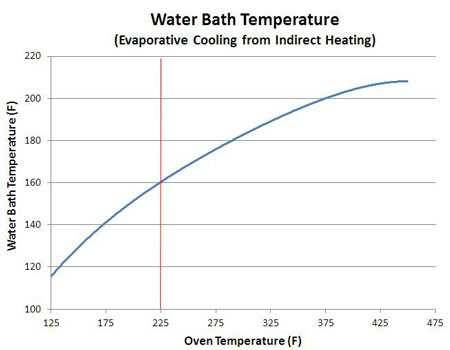

The higher the cooking temp, the shorter the stall, and in some cases, as you approach 300°F, there may be no stall at all. At higher temps, the energy overpowers the cooling effect of evaporation. But at lower temps, the two forces counterbalance each other and create the stall. Blonder discovered this principle by putting a bowl of water in an oven and setting the thermostat for 125°F. The water stalled at about 115°F. Then he put another bowl in at 175°F. It stalled at 140°F.

He repeated the experiment in 50°F intervals. With each step, the stall temp rose until it slowly approached the boiling point, 212°F with the oven just over 425°F. The bowl of water he cooked at 225°F stalled at 160°F. Well 225°F is the same temp of the smoker oven in his other experiments, not to mention the temp favored by most barbecue cooks, and 160°F is pretty close to temp at which smoking meat begins to stall. That’s the intersection of the red and blue lines in the graph above.

Blonder has done experiments which prove that the more airflow there is in the oven, the lower the stall temp. So the amount of draft in your smoker will impact the process. For example, pellet smokers, which have a fan in them, create a convection environment and that speeds the evaporation, so the stall can be shorter. And some electric smokers are so tight and humid, there may be no stall at all. Alas, there also may be no bark. A workaround that will help with bark in an electric smoker is to cook without the water pan and crank up the heat near the end.

Questions you may be asking

Why doesn’t the meat just stay in the stall until it is all dried out? Well, much of the moisture in meat is tied up and bound to other molecules like the collagen, fat, and protein. The supply of moisture that can evaporate is limited. Once the meat’s ability to supply moisture peaks, it gradually starts to heat up.

Anyone who cooks large cuts knows that it is common for them to lose as much as 25% of their weight during cooking. If you’ve ever collected the drippings, you know that the melting fat is nowhere near 25%. The weight loss is mostly moisture. Considering that meats are 60 to 70% water, that means there is still plenty of water left behind after the meat breaks out of the stall.

Will basting the meat, injecting, or putting a water pan in the smoker impact the stall? There is no question that extra humidity will slow down the cooking process, whether it comes from a water pan or applying a wet mop. When we baste, whether by mopping, brushing, or spritzing, we cool the meat just by the fact that the liquid is cool. It then sits on the surface until it evaporates, prolonging the stall. When we put a water pan in the cooker, the moisture evaporates from the surface and raises the humidity in the cooker, slowing the evaporation from the meat and slowing the cooking. In low and slow cooking, this allows the meat’s interior to catch up with the surface temperature.

Bottom line

Until reading Blonder’s results, I had always believed that water pans were important in order to keep the cooking chamber high in humidity, thereby reducing moisture loss from the meat. Apparently, water pans do this to some degree, but they also cause the cook to take longer. Bottom line: this is no reason to stop using water pans. The moisture in the environment of your cooking chamber mixes with the smoke there, influencing flavor and allowing the meat’s interior to catch up with the exterior so it cooks more uniformly. Water pans also help to stabilize temps in charcoal cookers by causing them to heat and cool more slowly, evening out temperature spikes and valleys. Most importantly, moisture condenses on the surface of meat and smoke sticks to it, increasing the smoke flavor.

Apparently, the stall is not unique to barbecue. Blonder has proven it can happen in baked goods. He points out that when we put ice cubes in a pan and turn on the heat, the ice remains at 32°F and even the water from the melting ice remains close to 32°F until all the ice is melted. This is a form of stall. Then the water in the pan rises to 212°F, the boiling point, and stalls there until the water is all gone, regardless of how much energy you apply to the pan. Same phenomenon.

When I showed this research to Sterling Ball, he roared, “I love it. It debunks the urban legend that it is the collagen or fat melting. And it makes great sense. This explains a lot! I can use this info!”

Myhrvold’s experiment

In Spring 2011, physicist Nathan Myhrvold published a landmark six book set named “Modernist Cuisine:The Art and Science of Cooking” ($625). This may be the most important cookbook since Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking in 1961.

In a short sidebar on page 212 of volume 3, Myhrvold describes putting two halves of a brisket in a convection oven set to about 190°F, one half wrapped in foil. His chart showed that the half in foil did not stall, and he theorized that the stall was evaporative cooling.

Barbecue purists complained that an indoor convection oven at 190°F was not a good test. The airflow in a convection oven is strong, perhaps encouraging evaporation and cooling. And most pitmasters cook at 225°F or higher, above the boiling point of water.

Blonder did his tests in a thermostat-controlled smoker at 230°F under conditions that a pitmaster uses. Blonder went beyond Myhrvold and did additional experiments to prove that the stall is not fat-related. And he demonstrated that meat won’t stall at higher temps. He also explains in more detail why the stall is not caused by collagen, and why the foil-wrapped meat is not steaming.

Scientists often regard data from one lab as suspect until it is confirmed by another. In this case, Blonder has confirmed Myhrvold’s experiment and added to our body of knowledge with important additional data.

What does this mean?

How can we use this info? As you can see from the last graph, one way to beat the stall and retain more moisture is to cook at a higher temp. And the fact is that more and more competition cooks are doing just that. They figured it out by trial and error. Many BBQ competitors now roast pork shoulder in the 250°F range, and others are cooking brisket north of 300°F.

Beat the bbq stall and retain more moisture with the Texas Crutch

But there is another way to prevent the stall, speed up cooking, and retain moisture. For years, competition cooks have employed a trick called the Texas crutch. The crutch is an old method of wrapping the meat with aluminum foil and adding a splash of liquid like apple juice or beer. It is popular on the BBQ competition circuit. The conventional wisdom was that the moisture creates a bit of steam that tenderizes the meat, and since steam conducts heat faster than air, it speeds up cooking. Typically, cooks wrap the meat when it hits 170°F or so, deep into the stall.

The truth is that there is no evaporative cooling inside the foil at 225°F. The foil prevents evaporation and over a period of hours, the temperature inside the foil slowly approaches a low simmer. Any moisture that comes out of the meat just pools in the foil along with the liquid the cook adds. “It’s like running a marathon in a raincoat. You’ll sweat, but it won’t cool you off.” There is fog inside the foil, but no steam cooking. Yet there is a form of braising! Braising is a wet method of cooking similar to stewing or poaching. But, the food is usually not completely submerged in a braise, as they are in those other methods. Braising is more like what happens in a slow cooker.

Final test

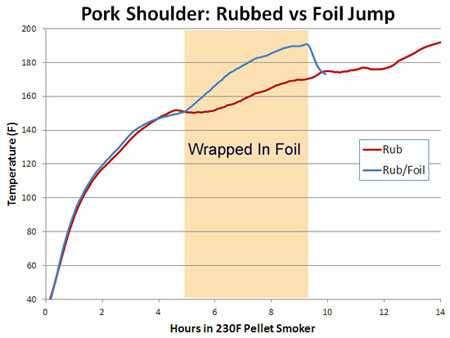

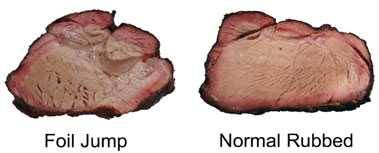

For his final test, Blonder took a six pound pork butt and divided it in two, removing the bone. He rubbed them both with Meathead’s Memphis Dust and put them into a 230°F cooker until the stall began. Then he wrapped one in foil and added 1 tablespoon of water. In the graph above, that one is the blue line, labeled “Rub/foil.”

The other piece of meat he left alone except for the rub, the red line labeled “Rub.” As you can see, the wrapped pork climbed to 180°F in about half the time, about six hours. He let it go to 190°F internal temp, a target I recommend. Then he removed the foil and put the pork back on the cooker to firm up the bark. As you can see, the temp dropped immediately after unwrapping, as the moisture evaporated and cooled the meat. After four hours, the unwrapped butt still had not passed 180°F.

The lines in the graph end when Blonder got hungry and when the foiled/unfoiled butt hit the same temp as the never foiled butt. He called the foiled butt “Really juicy and nearly perfect.” But “when the other one hit 180°F the meat was still slightly tough. It needed another hour or so to finish cooking in a kitchen oven.”

Here are photos of the two pieces of pork.

Remember this

If you are still clinging to the collagen myth, consider this: the conversion of collagen to gelatin occurs within the foil, yet there is no stall in there, so the phase change of collagen cannot be the cause. The fact that collagen melts at about the same temp as the stall is merely a coincidence, not the cause of the stall.

It is important to remember that once you remove wrapped meat from the foil, the temp will drop. This is because the moist surface begins evaporating and cooling almost immediately. Therefore, it’s best to take your meat up to its target temp, about 203°F, before you unwrap it. Otherwise, it could drop to as low as 175°F after unwrapping.

Meathead recommends

Based on Blonder’s data, you may want to wrap pork shoulders and beef briskets in heavy duty foil at about 150 to 160°F, after about two to four hours in the smoke. By then, the meat has absorbed as much smoke as is needed. If you wrap the meat then, it powers right through the stall on a steady curve and takes much less time. It also retains more juice. But wrap it tightly! If there are leaks, it might still stall.

Ball says that he is now following a similar protocol in competitions, and he is among the top money winners on the BBQ circuit. He won’t say what temp he cooks at, but he is now foiling when his bark is the deep mahogany color he wants, usually somewhere between 140 and 150°F. He leaves it in the foil all the way up to about 200°F (he wouldn’t say the exact number), takes it out of the cooker, lets it come down in temp to about 175°F so it stops cooking, and then wraps it and puts it in an insulated holding box called a cambro for an hour or two (see my article on how you can rig a faux cambro and my article on the difference between resting and holding).

Potential issues

For some cooks, there is a problem with the Texas crutch: the meat does not have a hard chewy bark on the exterior. Ball believes that a hard bark is emblematic of overcooked meat. He wants a dark, flavorful bark that’s tender not crispy. That may be the trend in competitions, but a lot of us love those crunchy shards of flavor (yes, please!). If you want a hard bark, the solution is to pull the meat out of the foil when it hits 203°F or so. Then hit it with direct heat on a hot grill to dry the exterior and darken the rub. Or just skip the foil altogether, do things the old fashioned tried and true way, and just be patient. Either way, the results are superb.

Second stall?

Many readers report a second stall when the meat goes north of 170°F. Here’s how Prof. Blonder explains it: “The stall occurs when the heating rate matches the evaporative cooling rate. Change either variable, and the stall temp moves. A second stall is very common when the meat is wrapped in foil if there is any small gap or hole in the foil. A leak in the foil permits evaporation and cooling. But a stall can occur without wrapping if the heat conditions change. For example, if the fire gets hotter, evaporative cooling can’t keep up and cool to 155°F, but it can keep up and stall at 175°F. Or if you spritz the meat, cooling rises and a second lower stall occurs. Or if the wind conditions change, less airflow lowers cooling, and the stall temp rises. A stable smoker has one stall.”

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators