Or, tumbling down an orthographic rabbit hole

While doing a little research this weekend, I came across an old piece in Interview magazine with Rick Schmidt, the owner of Kreuz Market, who offered this handy rule for identifying genuine old-school barbecue:

[Y]ou can tell the authenticity of a barbecue place by whether or not they spell out “barbecue.” You see it a lot of ways—barbeque, BBQ, bar-b-q. If you find the ones that spell it out, you can just about go in there and find out they’ve been around a long time. I learned that from my father [Edgar “Smitty” Schmidt], who wouldn’t have his name on anything that spelled barbecue the other way.

If you see a restaurant spelling it “BBQ” or “Bar-B-Q,” Schmidt added, “They’re pretty new.” Then he clarified, “pretty new means 50 years or less.”

That got me thinking about when and how those various shorthand spellings gained currency. It’s a subject I’ve dug into a few times in the past, and I originally concluded that Bar-B-Q and then BBQ became common terms amid the rise of barbecue restaurants in the early 20th century, but I wanted to go back to the archives and validate that.

I’m glad I did, for it seems the spellings are actually a good bit older, and there’s more to the story than I originally thought.

Meet Bar B.Q. Campbell

In Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, I include a sidebar that explores the many fanciful derivations of the word “barbecue” proposed over the years. No, it did not derive from the French barbe-a-queue, a supposed reference to cooking a whole animal (that is, “beard-to-tail”). That explanation, as the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary snootily put it, is an “absurd conjecture suggested merely by the sound of the word.”

I also scoffed at the notions that the word originated with a barbecue joint that offered whiskey, beer, and pool (“bar-beer-cue”, get it?) or from a rancher named Bernard Quayle who branded his cattle with a bar above his two initials—a.k.a. the Bar B-Q Ranch. I was convinced (and still am) that the English “barbecue” and the Spanish “barbacoa” were borrowed hundreds of years earlier from the native Caribbean word for a frame of sticks used for smoking and drying meat.

It turns out I should not have dismissed the Bar-B-Q Ranch tale so quickly, for there was indeed a ranch by that name in the late 19th century, and it was indeed owned by a rancher who branded his cattle with a bar over a B and a Q. His name, however, was not Bernard Quayle but Burton Harvey Campbell, and he was widely known as Bar B.Q. Campbell.

Caldwell [Kansas] Advance, February 2, 1882

Bar B.Q. Campbell sounds like a real son of a bitch, too. Born in western New York in 1829, he headed West after the Civil War, raised sheep in Illinois for a decade, then ended up in Kansas around 1880. Styling himself “Colonel B. H. Campbell,” even though he never served in the military, he set up a cattle ranching operation south of Caldwell in the so-called Cherokee Strip, a disputed stretch of land on the Kansas-Oklahoma border. It was meant to be a neutral, unsettled buffer between white settlers and Native American lands in Oklahoma, and Campbell ended up getting evicted by the federal government in 1883. He managed to keep right on ranching by leasing land from the Cherokee, and he illegally drove his cattle over the border into Oklahoma for grazing.

Those cattle were branded with a distinctive mark. In March 1885, the Oklahoma Boomer noted that, “his brand is a bar, B & Q, and he is known . . . as ‘Barbecue Campbell.’” The brand, it seems, came about as a play on the word barbecue, not the other way around.

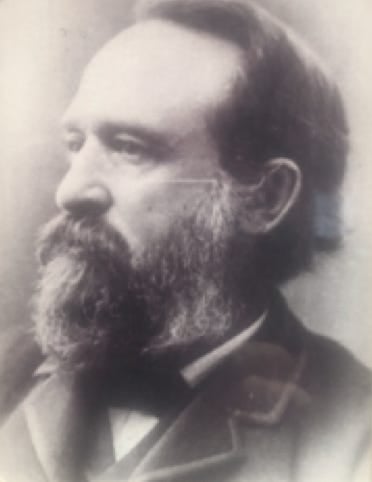

Burton “Bar B.Q.” Campbell

That brand got a tad tarnished after Campbell moved south to become general manager of the massive XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle, which comprised over 3 million acres. The land had been granted to a syndicate of investors led by Charles and John Farwell of Chicago in exchange for their constructing the new Texas State Capitol in Austin. In his history of the ranch, J. Evetts Haley describes Campbell as “big-faced, overbearing, loud-mouthed, personally penurious and institutionally extravagant” and chronicles an administration rife with mismanagement and fraud, including hiring outlaws as his cowboys and letting them rustle the XIT’s cattle. He was fired less than two years into the job.

Being big-faced, overbearing, and loud-mouthed isn’t necessarily a barrier to getting rich, though. Campbell moved back to Wichita and began building what is today known as Campbell Castle, a 17-bedroom, Scottish-inspired mansion overlooking the Little Arkansas River.

Campbell Castle, Witchita, KS. Courtesy Jeffrey Beall via Wikimedia Commons, CCA 3.0

Bar B. Q. Campbell continued his antics into the early 20th century. In 1905, the 75-year-old rancher was arrested for driving 913 head of mange-infested cattle from Kansas into Woodward County, Oklahoma, ignoring a Federal law that required herds to be inspected and dipped before crossing state lines. Three years later, his health failing, he died while traveling on a train outside Laredo.

So, I guess you can say Texas is where Bar-B-Q went to die.

Keeping Things Short

As far as I can tell, Bar B.Q. Campbell was not actually responsible for making Bar-B-Q a popular shorthand for “barbecue”. (Also, he didn’t intentionally go to Texas to die. He was actually returning home after traveling to Mexico in vain hopes of convalescing in the warm climate.)

The first instance I’ve turned up of the abbreviation being used for an actual barbecue event is in a letter from one Sissy May, who in August 1886 wrote to the editor of the Charleston Enterprise:

As we have seen no mention in your columns of the Bar B Q given at this place last week by Messrs. Greenwell and Bryant, we will say that the gentlemen deserve praise for the manner in which it was gotten up, as everyone attended pronounced it was an enjoyable affair.

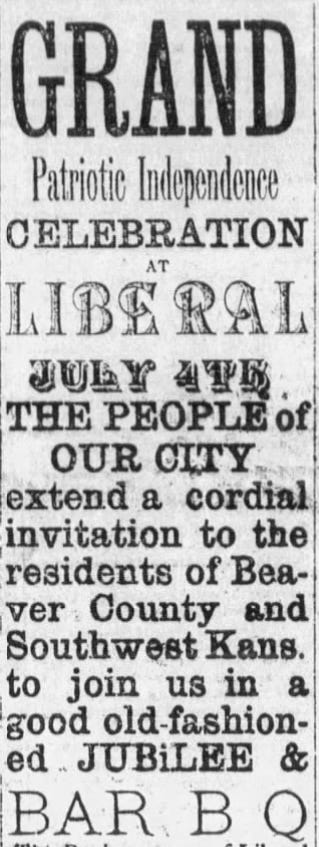

That’s the Charleston in Mississippi County, Missouri, by the way. Though it wasn’t common, a few writers in the decades that followed did save three letters by using the same abbreviation, as in this fancy ad from the Liberal Lyre of Liberal, Kansas, in 1891:

The dinner featured roasted hog, sheep, and ox and was followed by a sack race, a wheelbarrow race, and an egg race.

As the 20th century progressed, not everyone had the time for even five letters. Or perhaps we should say they didn’t have the room, for the three-letter term “BBQ” first appeared in newspaper columns and advertisements, where space was at a premium.

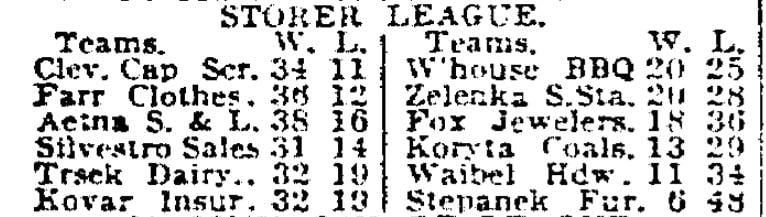

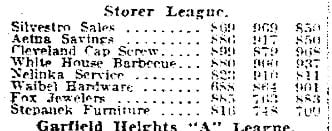

The was a “B B Q” brand of canned foods that was advertised in Midwestern newspapers in the 1910s and 1920s, but that seems to have just been three letters and not a reference to barbecue. (The products were things like peaches and beets.) The first usage I’ve found that seems to fit the bill appeared in Cleveland, Ohio (“Bomb City, U.S.A”) in 1930 in the Plain Dealer’s extensive coverage of local bowling leagues.

There were hundreds of teams in dozens of leagues (who says Cleveland doesn’t know how to party?) so in reporting the standings, the editor had to really pack things in:

So what might the name of the 7th place team at the top of the second column be? Perhaps “Warehouse Barbecue?” Or maybe . . . no, keep your mind out of the gutter. It’s actually White House Barbecue, as confirmed by other bowling coverage:

White House Barbecue was a lunch stand that operated from 1926 to 1931 at the corner of Lorraine and Denison Avenues, about four miles west of downtown.

That admirably compact abbreviation took a while to catch on. In 1939, a Wichita Eagle ad listed “Hickory Wood BBQ” as one of the restaurants selling Stern Brau beer, but it wasn’t until after World War II that the spelling became common. Perhaps it was a habit of economy learned during wartime rationing, but it seems driven more by cheapskates trying to save a few pennies on classified ads—especially real estate ads.

In 1945, $6,250 would buy you a “5 rm. wht. rustic” in San Jose, California, complete with a “Comp. roof. Enclosed rear yard and BBQ pit.” A realtor in Los Angeles offered an 8-year-old home with a “Lge. paneled Liv. Rm., 4 Bdrm, 3 1/2 Ba., extra lge. Patio, BBQ” for a “special price.”

At first, the vast majority of these classifieds—thousands of them—appeared in California newspapers, but by the 1950s the abbreviation had been picked up nationwide in classifieds as well as display ads. Grocery stores touted low prices on Woody’s BBQ Sauce and Oscar Meyer Wieners in BBQ Sauce (49 cents a can. Yum!) Despite Smitty Schmidt’s animus for the term, quite a few restaurateurs starting putting BBQ in their ads and on their signs, too. (Bar-B-Q, I will note, was even more popular.)

Some years ago in a Southern Living piece I called BBQ a “faux-acronym . . . one of the few terms in common usage that’s fully capitalized like an acronym but whose letters don’t actually stand for separate words.” In hindsight, I don’t think that’s quite right. BBQ, I would argue now, is indeed an acronym. It’s short for Bar-B-Q.

But we can get more compact still. Just outside of Lexington, North Carolina, is a barbecue restaurant called simply, “Tarheel Q.” In 2018 the Winston-Salem restaurant formerly known as Little Richard’s Lexington BBQ rebranded as “Real Q.” In 2008, Charlie McKenna opened a restaurant called Lillie’s Q in Destin, Florida, followed by another in Chicago plus a line of Lillie’s Q sauces. No one seems confused as to what kind of food these places serve.

But, still, I’m with the Schmidts on this one. When it comes to writing about barbecue, I tend to spell the word out in full.

Now don’t get me started on “barbeque.”

This dispatch was originally published in the Robert F. Moss Newsletter on Substack. Subscribe today for free to have his latest writing delivered straight to your inbox.

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators