The idea of putting sauces on food goes back pretty far. In the days before refrigeration and written history, somebody discovered that smoking meat helped preserve it. Somebody else discovered that soaking it in salty seawater helped preserve it. Somebody else discovered that packing it in dried salt helped preserve it. Somebody else discovered that leaving it in the hot sun or near the fire so it dried out helped preserve it. We now know that smoke and salt have anti-microbial properties, and that dehydrating foods also delays spoilage.

These prehistoric iron chefs discovered that they could also improve flavor and mouthfeel with smoke, salt, seeds, and leaves, as well as basting meat with wine, vinegar, and oils. Especially if the meat was on its way towards funky.

Preserved meats, especially dried meats, were often soaked in liquids to bring them back to life as stews, swimming in sauce based on such as water, oil, juices, dairy, and even blood. In fact the word sauce is said to come from an ancient word for salt.

According to Harold McGee’s superb book On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, in 239 BCE Chinese Chef I Yin, in “Master LÙ’s Spring and Autumn Annals” discusses the harmonious blending of sweet, sour, bitter, pungent, and salty, and the importance of balancing them harmoniously in sauces. “The transformation which occurs in the cauldron is quintessential and wondrous, subtle and delicate. The mouth cannot express in words; the mind cannot fix upon an analogy. It is like the subtlety of archery and horsemanship, the transformation of Yin and Yang, or the revolution of the four seasons.” The Yin and Yang of mixing sweet and sour is, of course, a Chinese specialty, and at the heart of most barbecue sauces.

McGee also quotes a Latin poem from 25 CE. It describes a farmer pounding herbs, cheese, oil, and vinegar, and adding it to a flatbread. The paste sounds quite a bit like pesto genovese, and the flatbread sounds like a pesto pizza or calzone.

Apicius, the famous Roman cookbook written in the 4th or 5th century, had about 500 recipes, more than 100 of them for sauces. Fermented fish sauce, called garum, was big in those days. Look at the ingredients list of Worcestershire sauce and you will find anchovies right near the top. Anchovies are a great source of the savory flavor component known as umami. Look carefully at the ingredients lists of modern barbecue sauces and you will often find Worcestershire. In fact Worcestershire is the backbone of the most obscure of our regional barbecue sauces, Kentucky Black Barbecue Sauce. Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce was introduced in England in 1837, and appeared in the US around 1849.

French, Italians, Spanish, and Portugese chefs became masters of sauces and gravies, and in a French kitchen the title of saucier is hard earned. In the Middle Ages, Europeans often used sweet grape juice in sauces, then wine, which is grape juice that has been fermented by yeast, and then vinegar, which is wine that has undergone a further fermentation by bacteria. Today, vinegar is in practically every barbecue sauce on the market.

One myth needs busting here. Contrary to what you may have read, sauces were not invented to cover the smell and taste of spoiled meat. Spoiled meat tends to make people sick or dead, so, although covering it with a sauce might make it more palatable, people who used this strategy probably tried it only once.

Sauces no doubt had roots in marinades and bastes. Marinades were employed to soak foods and moisturize it, or rehydrate dried foods, and as well as to flavor them. Bastes were employed to cool meat when cooking and replace moisture that evaporated or dripped off.

In 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue, and as the Spanish explored the New World, they discovered the natives had a wooden device for smoking fish, lizards, and small animals which to them sounded like “barbacoa“. Smoked meats were common in Europe long before Columbus, both for the flavor and because smoke helped preserve food, but the barbacoa technique was different and it quickly became popular with explorers.

In 1539 Hernando de Soto landed near Tampa, FL bringing with him nine ships and more than 600 men, far more than the 102 aboard the Mayflower that landed in 1620. But de Soto wasn’t interested in settling down. He was looking for gold and silver. He also brought hogs and vinegar with him. He made friends and feasted with some of the natives, and slaughtered others. The natives liked pork so much they often stole hogs from the palefaces.

Wine, malt, cider vinegar, salt, herbs, and smoke were common in Spain and probably traveled with Columbus and de Soto. They were used to flavor and preserve. Meat was often salted, dried, and then soaked before being cooked in stews. Sugar cane and molasses were plentiful in the Caribbean, chile peppers were native to Central America, and tomatoes probably originated in South America. Where there are tomatoes, there will eventually be tomato sauce, so it is highly likely that the first tomato sauce was made well before Spanish explorers first tasted it.

It is possible that sometime during de Soto’s alternating wars and parties with the natives, a confluence of smoke, pork, vinegar, chiles, and molasses all came together. There is some evidence that vinegar and peppers may have been at a feast with de Soto and the natives near Tupelo, Mississippi, and some evidence it happened a bit later in Virginia.

The Spanish colonized heavily in Florida and Mexico, the Dutch piled into New Amsterdam (now New York), the French set up shop in Canada and New Orleans, and Germans found the port of Charleston, SC hospitable. Each brought their culinary traditions with them and the sauces that they applied to the grilled and smoked barbecue meats of the New World reflected their preferences.

The first barbecue sauces were mostly butter. In “Nouveaux Voyages aux Isles d’Amerique” by Frenchman Jean B. Labot in 1693, there is a description of a barbecued whole hog that is stuffed with aromatic herbs and spices, roasted belly up, and basted with a sauce of melted butter, cayenne pepper, and sage, a popular technique from back home that probably came to the new world via the French West Indies by slaves and Creoles. The French are incapable of making anything without butter. The French also were big on meat juices in their sauces, an ingredient still found in some homebrewed Texas barbecue sauces and more recently in Adam Perry Lang’s Board Sauces.

The German fondness of pork with mustard resulted in the wonderful yellow barbecue sauces still popular in a band of South Carolina from Charleston to Columbia.

In 1867, just after the end of the Civil War, after all the slave cooks were freed, the Georgia widow Mrs. A.P. Hill published Mrs. Hill’s New Cook Book dedicated “to young and inexperienced Southern housekeepers… in this peculiar crisis of our domestic as well as national affairs”. It contains the first reference I have found for a sauce for barbecue. It is mostly butter and vinegar: “Sauce for Barbecues. – Melt half a pound of butter; stir into it a large tablespoon of mustard, half a teaspoon of red pepper, one of black, salt to taste; add vinegar until the sauce has a strong acid taste. The quantity of vinegar will depend upon the strength of it. As soon as the meat becomes hot, begin to baste, and continue basting frequently until it is done; pour over the meat any sauce that remains.” Interestingly, Mrs. Hill shares many “catsup” recipes, among them two for tomato catsup that are pretty close to what we know today. Originally ketchup was probably made from fermented fish.

The first mention of “barbecue sauce” I have found was in the Bolivar Bulletin from Hardeman County, TN in 1871. The author of an article thanks a Dr. J.H. Larwill for “a fine lot of Barbecue Sauce, of his own invention. For fresh meats of all kinds it cannot be excelled.”

According to an article in Eatocracy, several newspaper articles from the 1880s described barbecue sauces like Mrs. Hills: Mostly butter and vinegar seasoned with salt and black pepper, not unlike the sauces still popular on the coast of the Carolinas today.

The oldest recipes

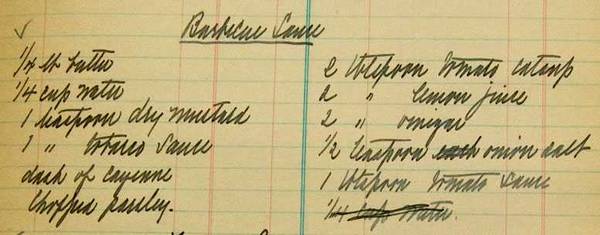

The first recipe I have found labeled “Barbecue Sauce” was in a handwritten cookbook by Edith Lockwood Danielson Howard of Providence, RI. I found it in the library of the Johnson & Wales College of Culinary Arts in Providence. The archivists there believe it was written about 1900, but the tomato sauce recipe mentions Crisco, which was introduced by Procter & Gamble in 1911 and, although it became very popular very quickly, this means the actual date is probably after 1912. As with other early sauces, it has a lot of oil. Interestingly, Mrs. Howard, a woman of means, did not cook. She had help to perform domestic labor.

Mrs. Howard’s Barbecue Sauce (1913)

This barbecue sauce recipe dates to the early 1900s and is one of the earliest I’ve found.

1/4 pound butter

1/4 cup water

1 teaspoon dry mustard

1 teaspoon tabasco sauce

Dash of cayenne

Chopped parsley

2 tablespoons tomato catsup

2 tablespoons lemon juice

2 tablespoons vinegar

1/2 teaspoon onion salt

1 tablespoon tomato sauce

Tomato Sauce

Mrs Howard’s tomato sauce is used in her barbecue sauce (above).

1/4 cup oil, crisco, or butter

1/2 cup chopped onions

Cook gently then add

1/2 cup green peppers

1/2 cup celery

1/2 cup carrots

2 1/2 cups tomatoes

1/2 cup tomato paste

1 teaspoon salt

1 bay leaf

Simmer 1 hour, stirring often or until as thick as cream. Use plain or strain.

You’ll notice that the recipe called for Tabasco sauce by name. The Louisiana hot sauce that is still used in many barbecue sauce recipes today has been around since 1868.

Martha McCollogh-Williams Mop and Sauce

Around the same time, in 1913, the witty Martha McCullogh-Williams wrote Dishes And Beverages Of The Old South. Born in 1848 on her family’s plantation in northwest Tennessee, she included many receipts, as recipes were called then, that she learned from her black “Mammy”.

She reminisces how her father made a mop and sauce for barbecue: “Daddy made it thus: Two pounds sweet lard, melted in a brass kettle, with one pound beaten, not ground, black pepper, a pint of small fiery red peppers, nubbed and stewed soft in water to barely cover, a spoonful of herbs in powder – he would never tell what they were – and a quart and a pint of the strongest apple vinegar, with a little salt. These were simmered together for half an hour, as the barbecue was getting done. Then a fresh, clean mop was dabbed slightly in the mixture, and was lightly smeared over the upper sides of the carcasses. Not a drop was permitted to fall on the coals – it would have sent up smoke, and films of light ashes. Then, tables being set, the meat was laid, hissing hot, within clean, tight wooden trays, deeply gashed upon the side that had been next to the fire, and deluged with the sauce, which the mop-man smeared fully over it. Hot! After eating it one wanted to lie down at the spring-side and let the water of it flow down the mouth. But of a flavor, a savor, a tastiness, nothing else on earth approaches.”

Chef Wyman’s Barbecue Sauce (1926)

In the December 6, 1926 Los Angeles Times, a food column called “Chef Wyman’s Suggestions for Tomorrow’s Meal” ran a recipe for lamb and accompanying it was a “Barbecue Sauce”. It said “Melt two level tablespoonfuls of unsalted butter in a small saucepan, add one teaspoonful of mustard, three tablespoonfuls of Worcestershire sauce, one teaspoonful of tarragon vinegar, three tablespoonfuls of tomato catsup, and a few drops of tobasco sauce.” Sounds good!

Pinkey Langley’s Barbecue Sauce (1930)

In the 1930s in the heart of the Great Depression, the Federal Writer’s Project deployed unemployed writers to collect info for a book called America Eats. WWII broke out in 1941 before it could be published. It contained several barbecue sauce recipes, among this one from Pinky Langley, a white man from Jackson, MS.

Juice of 6 lemons

3 lemons sliced

1 pint vinegar

3 heaping tablespoons sugar

1 heaping tablespoon prepared mustard

3/4 pound oleo

1 small bottle tomato catsup

1 small bottle Lea & Perrins Sauce

3 chopped onions

Enough water to make 3/4 gallons

Salt, black pepper, and red pepper to taste

His instructions were to mix the ingredients, cook for 30 minutes, and baste the meat every turn and turn frequently.

Sunset’s Barbecue Book Sauces (1938)

The first book about barbecue, “Sunset’s Barbecue Book”, published in 1938 by California’s Sunset Magazine, had three barbecue sauce recipes, recommended for marinating, basting, and serving. One, called “Herb Barbecue Sauce For Lamb” was given to a Sunset magazine by the great grandson of one of the first Spanish governors of California. It is a savory sauce with onion, garlic, rosemary leaves, mint leaves, vinegar, and water. “Barbecue Sauce For Steaks Or Hamburgers” had equal amounts of ketchup and olive oil, with butter, mustard, Worcestershire, grated onion and garlic, lemon juice, salt and pepper. Their “Circle J Barbecue Sauce” was more complicated and more like a Texas sauce with 2/3 cup butter, 1/2 cup ketchup, 3 cups water, and small amounts of onion, garlic, mustard, horseradish, herbs, A1 or Worcestershire, tabasco, chili powder, salt, black pepper, and only 2 teaspoons of sugar.

James Beard’s Basic Barbecue Sauce (1954)

James Beard’s landmark 1954 Complete Book of Barbece & Rotisserie Cooking offers several barbecue sauce recipes. His “Basic Barbecue Sauce” has 1 cup oil, 1 cup tomato sauce, 1 cup Worcestershire sauce,1 cup red wine vinegar, plus onions, garlic, green peppers, brown sugar, rosemary, thyme, and parsley.

Mr. & Mrs. Alinda Hobbs Barbecue Sauce

The art of “doctoring” commercial sauces has been around a long time too. Here’s a recipe from Mr. & Mrs. Alinda Hobbs near Greenwood, MS, in the Delta area, recorded by Eudora Welty in the late 1930s. I have only slightly rounded off some archaic measurements.

2 pounds butter

2 cups Wesson Oil

2 cups commercial barbecue sauce

1 cup vinegar

1 cup lemon juice

4 cups tomato catsup

1 cup Worcestershire Sauce

1 tablespoon Tabasco Sauce

2 cloves garlic, chopped fine

Salt and pepper to taste

Georgia Barbecue Sauce Company commercial barbecue sauces

The first commercial barbecue sauce may have been made by the Georgia Barbecue Sauce Company in Atlanta, GA. At the top of the page is an ad for it in the Atlanta Constitution in 1909. It says “Georgia Barbecue Sauce is the finest dressing known to culinary science for Beef, Pork, Mutton, Fish, Oysters, and Game of every kind; roasted, fried or broiled. It is also unequaled for perfecting Brunswick Stew and as dressing for Vegetables.” Alas, it is no longer made and I have been unable to unearth the recipe.

The oldest commercial barbecue sauce still made began in 1917 when Adam Scott opened a barbecue restaurant in Goldsboro, NC. Scott, a preacher, said the ingredients for his barbecue sauce came to him in a dream although the ingredients are nothing strange for the region. It was mostly vinegar. It was served in his restaurant until his son, A. Martel Scott, Sr., spiced up the mixture a bit in 1946. Scott’s Family Barbecue Sauce is still available today and is an East Carolina classic.

Numerous other barbecue joints have been around a long time and their sauces eventually found their way into bottles, onto grocery shelves, and now for sale on the web. Among them is another classic, Abe’s Bar-B-Q Sauce, first made in 1924 in Clarksdale, MS, in the Delta region, famous for both barbecue and blues.

A lot of websites say that the first bottled barbecue sauce was made by H.J. Heinz in Pittsburgh in 1948, but Louis Maull of St. Louis beat them to the punch by 22 years. Heinz may have been the first in broad national distribution, but not the first in a bottle.

In 1897 Maull began selling groceries from a horse-drawn wagon. He incorporated in 1905, grew steadily as a wholesaler of fish and cheese, began manufacturing a line of condiments in 1920, and introduced his barbecue sauce in 1926. It became so popular that’s about all they make nowadays.

In 1931, Mangham Edward Griffin made BBQ sauce for his family’s Fourth of July Picnic in Macon, GA. It built a reputation over the next four years. According to the company’s website, his brother, who owned a grocery store, suggested he bottle some. In 1935 the brother bought 12 bottles and sold them before Mr. Griffin could even get home.

In 1935 Griffin started his business of making sauce in his kitchen. He called it Mrs. Griffin’s Barbecue Sauce in honor of his wife and “because a woman’s name seemed to sell better than a man’s.” The company still makes three flavors in Macon, Original, Hickory Smoked, and Hot. It is mustard based, similar to the sauces in South Carolina.

Other commercial sauces were made and have now disappeared. On December 30, 1929, the Hamilton [OH] Daily News had an ad for Dinner Bell Barbecue Sauce at 15 cents per jar.

In 1930, ads for Ralphs grocery in the Los Angeles Times promoted Del Ray Barbecue Sauce for 12¢.

In 1942 there were ads for Derby Barbecue Sauce in the Mason City [IA] Globe-Gazette, in 1943 the Port Arthur [TX] News had an ad for Evangeinline Barbeque Sauce, and in 1947 no less than the New York Times had an ad for House of Herbs Barbecue Sauce.

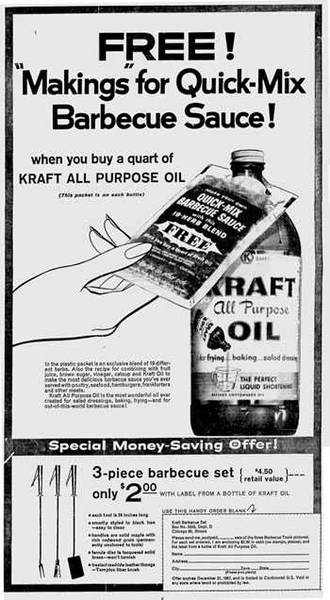

In 1957 Kraft began selling their all-purpose cooking oil with a packet of “Quick-Mix Barbecue Sauce” with a 19 herb blend and a recipe for mixing the two with fruit juice, brown sugar, vinegar, and catsup “to make the most delicious barbecue sauce you’ve ever served with poultry, seafood, hamburgers, frankfurters and other meats.” The ad shown here was from the Miami News included a coupon for a barbecue set for only $2 with a label from the oil.

Modern barbecue sauce

By far the most popular type of modern barbecue sauce is the Kansas City style, dominated by ketchup. Early ketchups were fish based sauces, more like Asian fish sauce or Worcestershire. Some were even mushroom based. Heinz introduced the first tomato based ketchup in 1875, and one can make the argument that most barbecue sauces are just a type of ketchup. Ketchup is tomato paste, vinegar, sugar and spices. The standard grocery store Kansas City style barbecue sauce is ketchup, vinegar, sweeteners, herbs, spices, and liquid smoke. In other words, they are really just amped up ketchup. The ratios of these ingredients among the brands varies, and a few minor herbs and spices give them individuality.Click here to read more about ketchup and how to make your own.

Many modern barbecue sauces have high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in them, an ingredient that is controversial. Click here to read more about corn syrups and my take on the controversy.

Many commercial sauces also contain liquid smoke, which is smoke from burning hardwood that has been captured and dissolved in alcohol. When added to sauces it contributes another layer of flavor, simulating, but not duplicating, the flavor of hardwood smoke from the cooker. Purists hate it, but if you have no way to cook outdoors, it can really help.

Here are some recipes for the regional sauces:

- The Different Barbecue Sauce Types

- Kansas City Classic BBQ Sauce

- Tennessee Hollerin’ Whiskey Sauce

- South Carolina Mustard Sauce

- Grownup Mustard Sauce

- Lexington Dip

- East Carolina Mop-Sauce

- Louisiana Bayou Bite Sauce

- Texas Mop-Sauce

- Danny Gaulden’s Legendary Glaze

- Alabama White Sauce

- Kentucky Black Sauce for Lamb & Mutton

- Eve’s Apple Butter Pig Paint

- Spiced Apricot Glaze

- Chocolate Chile Barbecue Sauce

- Jazzy Hog Competition Barbecue Glaze

- Other Fun Sauce Recipes

- Commercial Barbecue Sauces

- The History of Barbecue And The Origin Of The Word

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators