Mom always said that you had to rest an hour after eating before going for a swim. Happily, there has never been a documented case of drowning due to swimming after eating. Clearly this is a myth, but I still obey Mom because, well, she’s Mom.

Likewise it is widely preached that we must let meat “rest” after it is cooked for fear that we might drown in all the escaping fluids when we cut it. Many chefs proclaim it is crucial. Let’s define some terms:

Resting meats cooked to 165°F or below, we are told, makes meat more juicy. Steaks and chops are said to need 15 minutes, thicker roasts and turkey breasts are said to need up to 30 minutes.

Holding some meats cooked up to 200°F or so, like barbecue beef brisket or pork butt, is very different from resting meats cooked to less than 165°F.

Let’s start by focusing on resting meat cooked to 165°F or below. Is it necessary? Hint: Much of the answer lies in the photo above. To get the whole answer, we need to look at:

- What causes juiciness

- What happens to meat when it gets hot and when it leaves the heat

- How we eat in the real world

- Some of the experiments people have done to test the theory

Some facts about meat

Think of meat as a protein sponge. Raw muscle is about 70% liquid. This liquid is not blood, which is dark red, almost black, thick, and it clots. There is no measurable blood in a properly slaughtered and butchered animal. Most of the liquids in muscle are myowater, water laden with the protein called myoglobin.

Myowater is thin and usually pink, and it doesn’t coagulate like blood, which is thick and dark red. It is what you see on your plate when you cut into a piece of meat fresh from the heat. Remember, Zuzu, everytime someone calls it “blood”, somewhere a teenager becomes a vegetarian.

What we call juiciness is not just a matter of how much water is in the meat we are eating. There are many factors.

Some facts about juiciness

Food scientists tell us that when we taste meat, the most important measures of quality that we look for, in this order, are

- Tenderness

- Flavor

- Juiciness

What we perceive as juiciness is complicated. In the journal Meat Science, in 2011 Pearce, et al, surveyed the literature to present a summary of what is known of water in meat and they say “Total water content of the meat and cooking loss cannot explain juiciness of the cooked meat product.”

Scientists have machines that can measure tenderness by the amount of pressure needed to pierce a piece of meat, but there is no machine that can measure juiciness. Although a typical steak is about 70% water before cooking andabout 60% after cooking, juiciness is a human perception, not a subjective measurement. The AmazingRibs.com science advisor, Prof. Greg Blonder explains “In a steak, going from 70 to 65% water might be unnoticeable, but 45 to 40% might take you from edible to a cardboard. Beef jerky is still 25% water by weight, but most people would say it was juiceless.”

So what influences juiciness?

- Free water in the raw meat.

- Water bound with proteins.

- Where the water is located within the architecture of the muscles.

- Melted and softened fats, especially marbling.

- Gelatinized collagen.

- Saliva which is activated by seeing and hearing sizzle, as well as seasonings, especially salt.

So some juiciness has nothing to do with water. Some meats like pork ribs, pork butt, and beef brisket are often smoked low and slow up to more than 200°F, waaaaaay past well done, well into the zone where water is supposed to disappear, and much of it does, especially as the surface dehydrates and “bark” is formed. But these cuts get their juiciness from rendered fat, melted connective tissue, and salty rubs that force you to salivate (see my article on meat science).

There are other factors that impact juiciness:

- Drip loss in the package.

- Cooking method.

- Cooking temperature.

- Meat temperature when removed.

- Breed of the animal.

- Age of the animal.

- Aging of the meat.

- The muscle(s) being cooked.

- How was it packaged?

- Was it frozen and how it was frozen?

- How was it stored?

- What was it fed?

- How was it slaughtered?

- Was it mechanically or enzyme tenderized?

- Cooked with the fat cap on or off?

- Was the meat brined, salted, or injected?

- What seasonings, spices, herbs, tenderizers, and especially salt, that encourage saliva flow are used?

- Wine!

When you cut into raw meat there is practically zero loss of liquid. Even if you grind meat for burgers there is no real liquid loss. That’s because the liquids are bound by proteins and held by capillary action in the thin spaces in the muscle and between the muscles. Raw meat in the grocery display case might have 1 to 3% “drip loss” which is why they put that little absorbent pad under it. Much of this drip loss is due to the rupturing of cell walls while the carcass goes through rigor mortis, a shrinking and stiffening of the muscles after slaughter. Within a day, enzymes kick in and begin the tenderizing and aging process and the muscles relax. This is why freshly killed meat can be tough. It is usually best to let it rest a day or three.

If the meat has been frozen, water expands and ice crystals form. Remember the last time you stuck a bottle of wine in the freezer and forgot about it? It froze, expanded, and blew out the cork. These ice crystals puncture the cell walls and, depending on how the meat was frozen and thawed, another 3 to 5% of “purge” can emerge when the meat is defrosted.

During cooking, according to Prof. Blonder, “The first ‘sweat’ occurs with water that is very loosely contained between fibers oozing out through relatively wide channels in the meat. Some of it drips off and some evaporates. As the heat increases, more tightly bound water is freed. Then, around 160°F, the collagen in the connective tissues that sheath muscle fibers and hold together bundles of fibers begin to shrink and eventually soften into gelatin. This squeezes on the muscle fibers, wringing out additional liquid, some myowater, and some myoglobin from burst cells. So the amount of released juices rises as you pass through 160°F. This is why meat cooked to higher temps gets dry.” The exception is sous vide cooking for many hours at 140°F.

Depending on how hot and how long you cook, there might be 10 to 25% water loss, mostly due to evaporation and dripping. Let’s call it 15%. So a properly cooked steak is down to about 60% water, but most of it cannot escape when the meat is cut because it is bound by proteins and held by capillary action.

Sous vide sucks out a lot of water but the meat still feels juicy

If you have ever played with sous vide, a very gentle method of precise temp control cooking (click here to learn more), you know the meat is drowning in water in the bag. The low slow gentle process can pull out a lot of juice. But the meat is exquisitely tender and juicy. So clearly meat can lose a lot of water and not taste dry.

Dry aged steaks don’t exude anything but flavor

I once had dinner with three friends at David Burke’s Primehouse in Chicago, now closed. Chef Rick Gresh served a vertical tasting of 28, 40, 55, and 72 day dry aged ribeyes. He says they rest for about six to nine minutes in the process of being plated and brought to the dining room under lids. The waiter sliced each steak into 3/4″ strips so we could all taste each steak. Despite all the cuts, there was no juice lost. Zero. Zilch. Zip. I asked Chef Gresh why and he said “that’s dry aging.”

Dry aging dehydrates the meat and enzymes change the molecular structure, but even though there was significant water loss due to aging, the meat was tender and juicy. Clearly juiciness is not all about water.

Why all the books say we should rest our meat

There are several theories for why we should rest meat. Let’s look at the most popular:

The pressure theory. The most widely repeated theory says that during cooking, muscle fibers, which fans of resting say are like tiny skinny balloons, shrink along their length and expand across their width. Just like when you see meat “pulling back” along the bone. This puts pressure on the juices between the balloons and at the same time these juices expand pushing even harder on the balloons. If you cut into the meat when it is fresh off the heat, they say the juices come gushing out of the sliced balloons. If you let meat rest and cool, say the resting advocates, water pressure drops, fibers relax, and fewer juices escape. A variation on the theme says that the juices run away from the heat on the side facing the flame.

Not so, says the AmazingRibs.com meat scientist, the late Dr. Antonio Mata, “Water moves back and forth between compartments. It is not trapped in the fibers. Fibers are not balloons.” So the pressure equalizes quickly. And at cooking temperatures, water does not expand much inside the muscle. Meat shrinks during cooking mostly because of dripping and evaporation.”

Harold McGee, author of the definitive food science guide “On Food And Cooking” says “It’s disengagement of the water from the fiber proteins as they coagulate and bond to each other increasingly tightly. Raw meat has a higher water content than cooked meat, and ~85% of it is tightly held in the myosin-actin filaments. But raw meat isn’t juicy, it’s mushy. As the filament proteins coagulate and actually shrink, there’s less room between them for the water, and some of it can then flow relatively ‘free.’ Some stays in the cells, some moves into the spaces between cells. It can then leak out from cells and spaces through cuts.”

Mata adds “If the water was somehow pushed into and trapped inside expanding balloons, then, when the fibers cool during resting, they would shrink and would expel more liquid, not less as a result of resting. Furthermore, water cannot be compressed by pressure under cooking conditions. In other words, this theory just doesn’t hold water.”

The reabsorption theory. Another theory holds that the outer parts of the meat, which are much hotter than the centers, dry out during cooking making the beloved crust. This is true. The hotter you cook, the more gray dried out meat forms directly below the surface. This is less lovable. This is overcooked meat with less flavor, water, and tenderness. By allowing the meat to rest, says the theory, these hot dry fibers can absorb some of the liquid from the center, so less liquid will spill out when you cut the meat. This may be partially true because systems do seek equilibrium but it can take a while for dry meat on the surface and just below it to absorb water from further below it.

The viscosity theory. This theory is that when the meat is hot the juices are runny and as they cool they get thicker and more viscous. Sounds plausible, but I have never seen any real research to demonstrate this.

Why I think resting is a mistake

But resting has other impacts, many detrimental.

Cold meat! Another important thing happens during resting: The meat gets cold. There’s a reason the serving plates are hot in steakhouses. We like our meat hot. It will cool off fast enough, why give it a running start?

Overcooked meat! Another thing happens when the meat is resting: Carryover. Depending on the thickness and the amount of energy stored in the outer layers, the center can rise 5 to 10°F. That can take your perfectly cooked steak to particle board before you know it.

Waxy fat! When a steak is hot, the fats are soft, sometimes even runny. They give the meat a rich unctuous mouthfeel and a lot of flavor and contribute to the juiciness sensation significantly. Let the meat cool and the fat starts to harden and get waxy.

Soft surface! While resting, the crust of a steak or chop gets soft and wet, especially on the side that is in contact with the plate or cutting board. Spice rubs get muddy. Adam Perry Lang is a classically trained chef. I asked him to weigh in on this. He points out that the juiciness sensation also depends a lot on the crust, especially its saltiness. “Fresh off the grill, fat, collagen, and salt will cause a unique flood of saliva in your mouth. It is the type of crust that can cause you to eat clumps of fat and chewy sinew with joy that you would not normally eat. I am convinced it is another dimension, or the epitome of umami [savoriness]. It rarely comes the same way from a rested piece of meat. Finishing salt is also important for this juiciness sensation.”

Rubbery skin. Hot chicken and turkey should have crispy skin. Rest it for 15 minutes or so, especially under foil, and it turns to rubber.

So resting cools the meat, softens the crust and skin, overcooks the center, muddies the spices and herbs, and reduces moisture of steaks and chops, and its impact on the perception of juiciness is probably nil.

Here’s a great video by food scientist Chris Young 10+ years after I wrote this article showing you I was right and I am no longer alone!

Here’s a great article by Daniel Gritzer at SeriousEats.com titled “This Major Rule About Cooking Meat Turns out to Be Wrong”

https://www.seriouseats.com/meat-resting-science-11776272

Foil makes it worse

A loose tent of foil is often suggested during resting, especially for turkey. Not only does it not help, it hurts! It does prevent a little heat from escaping, but not much. Foil is a lousy insulator. If you take a dish from the oven that has cooked under foil, in seconds that foil is cool enough to handle. The problem with foil is it traps steam which softens crust and can turn crackly poultry skin to rubber in minutes. And never wrap cooked meat tightly in foil. Juices really come gushing out then.

Attempts to prove the importance of resting

To get a handle on how much leakage occurs with and without resting, one would have to do carefully controlled lab experiments and repeat them multiple times on different cuts from different animals. But remember, that is only a measure of water loss, not juiciness!

Food scientists use centrifuges, nuclear magnetic resonance relaxometry, and other high tech tests. But that hasn’t stopped cooks from attempting to get a measurement.

Prof. Blonder’s experiments on steaks

I asked Prof. Blonder to look into the matter.

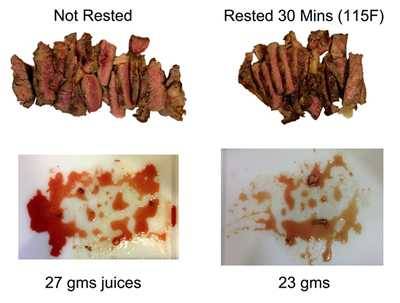

He started by taking two 13.5 ounce ribeyes, each 1.5″ thick, salted them with 1/3 teaspoon of table salt per pound, and let them sit for an hour or so in the fridge. This technique is called dry brining and is known to help the proteins retain moisture as well as improve flavor. He then cooked them to 125°F, medium rare, using the reverse sear method I recommend because it produces more tender and less overcooked meat.

He immediately cut one steak into strips, collected the juices in a paper towel from the cutting board and the meat surfaces, weighed the towel on a sensitive scale, and subtracted the towel’s dry weight. The “not rested” steak expelled about one ounce by weight through the whole process, most of it on the cutting board. about 7%.

Within five minutes juices started emerging from the “rested steak” which sat for 30 minutes before Blonder cut it up. After he cut the meat up, he collected the juices, most of which were on the meat surface not the board, and weighed them. The total was about 0.85 ounces or 85% of the one ounce collected from the not rested steak. An insignificant difference of 0.15 ounces less juice expelled. Also, the meat temp rose to 145°F from carryover cooking, well past medium rare. Carryover could explain the fewer juices since the warmer meat is, the fewer juices it discharges. Not much juice left in a well done steak. Is carryover the reason people think resting meat preserves juices?

To make sure his data was correct Blonder repeated his tests. Same results. And remember, Blonder did something most adults don’t do: He sliced up the meat all at once. Most of us cut it one bite-sized slice slice at a time, eat it, then eat some green beans, then some potatoes, then a sip of wine, and then we cut another small bite-sized slice. So by this measure alone, resting meat has no significant benefit.

J. Kenji López-Alt’s experiments on steak

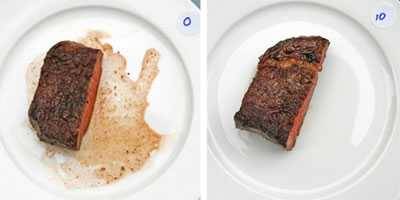

At SeriousEats.com, the brilliant chef J. Kenji López-Alt took a serious stab at testing the resting theory. He took six steaks, raw weight of about 17.6 ounces, pan seared and oven finished and cut one in half immediately, and others at 2.5 minute intervals. There was no carryover cooking. Below are an unrested steak, and one rested for 10 minutes. You can clearly see the rested steak has spilled less liquid.

He then dried the surfaces of the cut steaks, then weighed the meat. The weight loss from an unrested steak was 6% greater than a steak rested for 5 minutes, just less than 2.5 tablespoons, or less than 1/10 teaspoon per bite.

Of course much of the juice on the surface of the meat is ingested, and most of us don’t begin eating a large steak by cutting it in half. The amount of area exposed by the cut is vital to determining how much spill there is. Most of us cut off a bite sized chunk from an edge, exposing much less surface area which is cooked more and will spill less. If you think about the time lapse between moving the steak from cooker to table, and from first cut to the second, five minutes can easily pass. If you mop up the juice with meat on your fork, in the real world, there is little to be concerned about and nothing is really lost.

Helen Rennie’s experiments on steak

A computer scientist and food blogger from Boston, Helen Rennie, ran a test similar to Lopez-Alt’s. She also cut the steaks in half but she measured the juices by pouring them off the plate. She found little difference in juices lost. Pouring juices off the plate is probably not the best method to assay juice spillage since there is inevitably juice left clinging to the plate.

Heston Blumenthal’s experiments

The great English Chef Heston Blumenthal attempted to demonstrate the necessity of resting steaks by cooking two steaks in a pan. He immediately placed one on a plate, covered it with a sheet of Plexiglas, and had his very large assistant, Otto, smash it under foot. He poured the liquid off the plate into a shot glass. He got about two tablespoons. He let the other steak rest for five minutes and then gave it the Otto treatment. Only a few drops emerge.

So the difference was a 1/2 an ounce by volume (also about 1/2 ounce by weight) from a whole steak that probably weighs 10 to 12 ounces total. If you cut this steak into bites, failure to rest might cost you one or two drops of juice per bite compared to a steak stomped on by Otto. Blonder points out that, as steaks rest, the juices get slightly more viscous, so perhaps the amount of juices recovered by Blumenthal is simply a matter of fluid dynamics. The thicker juices are just sticking to the meat. Maybe the real message is to keep Otto out of your dining room. You can watch his demonstration at about 2 minutes 50 seconds into this video.

Cook’s Illustrated’s experiment on pork loin

Over at America’s Test Kitchen, a subsidiary of Cook’s Illustrated, a magazine I highly respect, Dan Souza took several 3.7 pound pork loin roasts, perhaps 3″ thick and 12″ or more long. They cooked them at 400°F til they reached 140°F internal temp, and then let them rest for different intervals wrapped in foil. They then cut them into 1/2″ slices and collected the juices in a bowl.

They say that the roast that was sliced immediately lost 10 tablespoons. The one that rested 10 minutes lost only four tablespoons. Other intervals lost less. I’m not sure how accurate the 10 tablespoons measurement is since they say that the juices ran off the cutting board, and the picture on the site shows them ready to wipe it up with a cloth.

Regardless, let’s do the math. If the roast was 60% water, a conservative estimate for this cut, then it contained 2.2 pounds of water raw. That’s about one quart, and that’s about 64 tablespoons, so the loss of 10 tablespoons was about 15% of the water. Waiting 10 minutes reduced the loss to four tablespoons, about 6%. The difference was 9% of the moisture. Why? This is a thick cut of meat and there is more surface breached.

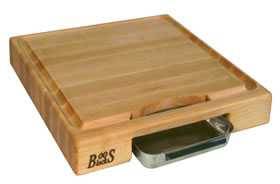

So maybe it makes sense to rest this cut for five minutes if you allow for carryover, but I wonder how many of us can tell a loss of 9% of the water, especially now that we know that the perception of juiciness depends a lot on things other than water content, especially since this cut is often served with a sauce or glaze. And again, remember, the juices are not lost. They are right there on your cutting board. I sure hope you don’t leave them there. I hope you have a cutting board that can capture these juices so they can be poured over the meat. See below for a beauty.

Prof. Blonder’s experiments on pork loin

After his experiments on steaks, Blonder turned his attention to pork loin roasts like Cook’s Illustrated. He wanted to see if the size of the meat, but more importantly, the final temperature relative to 140°F when the collagen shrinks, made a difference.

So, he took roasts 6″ long, 4″ wide, 3″ tall, weighing 2.2 pounds, and roasted them in a 400°F kitchen oven. Pork loin has very little fat, so any weight loss during cooking and cutting is mostly water. As with the steaks, he salted the meat with 1/3 teaspoon of table salt per pound a few hours before cooking, just as a good cook would.

He then cooked them, removing them at 140°F internal. During cooking they lost about 20% of their weight due to dripping and evaporation. One sat three minutes and then he cut it into 3/8″ slices, the other waited 20 minutes before slicing. After slicing he waited five minutes and collected the juices and weighed them. The difference seemed significant: three ounces came out of the unrested meat compared to two ounces from the rested meat. But that’s only a diff of one ounce from a 33 ounce roast!

One might say that this is an ounce of precious liquid lost, but Blonder then poured all three ounces from the unrested meat on top of the slices, like most of us do after carving, and the meat drank up about an ounce, so what remained was precisely the difference between the rested and unrested meat!

But here’s the capper: The resting meat was steaming hot, and moisture evaporated as it rested. He measured the loss, about 1/2 an ounce, and if he tented it with foil, it lost almost 3/4 an ounce. That’s most of the difference between the rested and unrested meats. The unrested meat lost naught to evaporation because slicing cools the meat so rapidly.

He also points out that salting the meat before cooking helps retain moisture by altering the proteins so they hold onto water better.

Click here for more details of Blonder’s experiments.

Jess Pryles’ sponge analogy

Blogger Jess Pryles vastly oversimplified the resting concept in a video by dunking a sponge in water to represent a piece of meat. She then squeezed out the water to demonstrate loss during cooking. She then shows how the sponge resumes its original shape and says that resting allows the water to redistribute. But how? It was squeezed out. It dripped into the fire. The sponge resumes its shape by sucking in air. And when meat shrinks it does not resume its original shape. Remember the laws of physics say you cannot compress water under normal conditions!

What does Harold say?

Here is what the eminent food scientist Harold McGee says in his foundational book On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen: “Large oven roasts should be allowed to rest on the countertop for at least half an hour before carving, not only to allow the ‘afterheat’ to finish cooking the center, but also to allow the meat to cool down, ideally to 120°F/50°C or so… As the temperature drops, the meat structure becomes firmer and more resistant to deformation and its water holding capacity increases. Cooling therefore makes the meat easier to carve and reduces the amount of fluid lost during carving.”

He makes no mention of steaks, only large roasts. And, while much of the book is footnoted with references to research, there are no footnotes on this passage. Blonder has proven that a slightly greater amount of liquid may come out of a roast, but it is a small percentage of the total liquid, and it is not “lost”. It is reabsorbed when poured over the meat. And remember, juiciness is only partially dependent on the myowater and in the meat. So now we know that the only remaining reason for resting is to make a large roast easier to carve.

Let’s get real: How do you eat?

Let’s forget all the science now and just think about how we eat. Let’s be conservative and say finished meat is about 60% water after drip loss, purge, and cooking. That means that, in a 13 ounce steak, 7.8 ounces are liquid. That’s almost a cup. So let’s say we pull our nice big thick juicy medium rare steak off the grill and cut into it. Out come some juices. A little more than a teaspoon out of 13 ounces of steak that is a cup of water.

Do you let those juices sit on the plate and waste away? Heck no. You mop them up with the meat on your fork! The meat is absorbent now that it is not longer saturated with water. Nothing is lost!

Do you inhale the whole steak immediately? Heck no! It takes a few minutes to get it off the heat and to the table. Then it takes at least 15 minutes to eat it. The fact is, by the time the steak comes off the heat til you get two or three bites in, have a bit of potato, a bit of the green beans, a sip of wine, a little conversation, the meat has had plenty of time to rest, and not a drop of fluid is wasted because when you are done, your plate is clean. And the steak was hot and crisp when you cut into it.

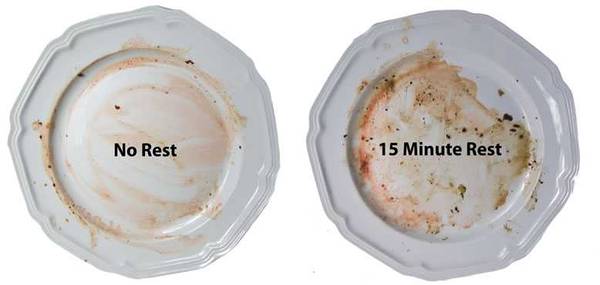

Look at the two plates at the top of the page. No juices left behind! The plate on the left shows juices from a steak that did not rest. The plate on the right held a steak that rested 15 minutes. Not much waste is there? That’s because my wife and I mopped up all the juice we could with the meat on our forks. (The slight color difference is because one steak had a tiny bit of char on some of the fat and it colored the juice.)

Thick, dry-aged porterhouse is the specialty of the house at one of the most beloved beef emporia in the nation, Peter Luger Steakhouse in Brooklyn. It is cooked under a screaming hot gas broiler to medium rare, and then, to halt the carryover cooking, the two sections are sliced from the bone, and sliced again into hunks so several people can share it. It is served swimming in its juices. See those spoons in the picture above? They are for saucing the meat on your plate with the juices in the platter. I sincerely doubt any steak has been sent back to the Peter Luger kitchen for being too dry.

What about roasts and large cuts?

Because a beef rib roast, pork loin, or turkey breast can be so much thicker than a steak, when you slice them there is much more surface area to leak juice. So the amount of juice exuded from a roast can look alarming.

Will more liquid flow without resting? Blonder says “no”. By slicing right away I get to serve perfectly cooked hot meat. I collect the juices from the cutting board and I pour them over the meat on the serving platter. Most of the juices are re-absorbed. Or I make a board sauce (especially on leg of lamb). This is a great way to use the juices and add some excitement. Trust me, I never serve improperly cooked or dry roasts.

I have even used a cutting board with a slot to collect juices, a real beauty, the John Boos Newton Prep Master Reversible 18″ Square Cutting Board with Juice Groove and Pan shown here.

The best reason Blonder sees for resting a big roast like a prime rib is that it stiffens slightly and is easier to carve, as described by Harold McGee. A sharp knife solves any cutting issues.

Holding meat like brisket is not the same as resting meat

Remember:

Resting is the term for letting hot meat cooked to normal temperatures cool as discussed above. Typically these are meats cooked to 165°F or below.

Holding is the technique of letting meat cooked well past well done stay warm for a while after cooking. Typically these are meats cooked in the 200°F range, like beef brisket, pork butt, and ribs.

In restaurants brisket, pork butt, and ribs are often removed from the 225°F oven, wrapped in foil or plastic wrap, and placed in a warming oven to hold for a few hours at 170 to 180°F. Some of these ovens even have humidity control. In competitions the meats are often wrapped in foil and then towels and placed in an insulated box like a cambro or faux cambro.

These are very different meats than steaks, chickens, chops, etc. They are really tough cuts with lots of fat and connective tissues that need to be cooked to a high temp to make them chewable. A steak cooked to 203°F would be inedible, but a brisket is at its best at about that temp. Rendered fat and gelatin from connective tissues provide most of the juiciness. In fact they often can lose up to 30% of their weight during cooking, most of that “drip loss” is water that has evaporated from the surface. Read more about this in my article on meat science.

During the holding period, very gentle slow carryover cooking continues to cook the meat and tenderize it as it cools slowly, and it rarely is allowed to cool to less than 180°F, much hotter than a medium rare steak or even a turkey.

Because these meats have been cooking for 8 to 12 hours, the surface has become dry, forming a jerky-like bark. What water is left is in the center. By wrapping it so no more water will evaporate, and cooling it slightly, that water can move back into the parched areas.

The problem is that if you let it go too long, it can soften the bark too much. It is a balancing act, and that is why to top cooks are called Pitmasters.

The bottom line

1) The difference between the amount of juice spilled with resting and without resting is insignificant especially when one considers that juiciness depends on many other factors such as water that remains bound with proteins, melted fat, collagen converted to gelatin, and even saliva.

2) Far more important than resting the meat is cooking it to the right temperature. Once you get beyond 140°F, the moisture from water in any meat drops precipitously. The ultimate folly is the diner who orders a medium steak (140°F) and insists that it rest for 20 minutes. As meat sits around it can easily overcook from carryover. The best way to make sure you cook it properly and use a quality digital thermometer. I cannot stress this enough. Follow the red link and buy one that I have tested and recommended.

3) Season your meat properly with adequate salt, then, when the meat hits the proper temp, dive in while it is hot and crisp! Sizzling crisp crust is a major pleasure factor, perhaps more important than the small amount of water spilled. Chef Dave Arnold, author of the blog Cooking Issues, The International Culinary Center’s Tech ‘N Stuff Blog, says “Extra juice makes meat taste watery and bland. Moisture isn’t necessarily your friend; delicious is your friend.”

4) Juices lost in the grocery case, after thawing, and during cooking are far greater than those spilled after cooking.

5) In tests like Kenji’s, five minutes rest was all that was needed to stanch most of the flow. In Blonder’s tests, resting made no significant diff. If you still think resting matters, rest assured your meat will rest enough while you move it from cooker to the table, while you wait for everyone to be seated, while you taste all the other foods and drinks, and by the time you’re into it more than a slice.

After this article was published, Kenji proposed a very clever compromise: “I cook the meat, then let it rest. Just before serving, I flash it on the hottest fire I can muster for about 15 seconds per side. If I’m cooking indoors, I sear the steak in hot fat, then let the meat rest on a wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet. Then, just before serving, I reheat the fat and juices left over in the skillet until they’re smoking-hot and pour them right over the steaks—you’ll see them sizzle and sputter as they crisp up. This is similar to the restaurant hot-oven flash, but it works even better: Hot fat is a more efficient means of heat transfer than hot air, which means faster crisping with less chance of overcooking. It also adds a final shot of flavor to the surface of the steak.” Click here to read the rest of this thoughtful article.

6) But most important, leave no juices behind! Blonder proved that meat will soak up almost all the juices spilled, rested or not. Pour the juices over the meat, and mop the rest up with the meat on your fork, with potatoes, rice, bread, or make a board sauce with it. Look at the picture at the top of the page. That should end the debate.

This myth is busted. Like the other myth that won’t die, resting before swimming, when it comes to all this talk about resting meat, I say give it a rest, stop crying over spilled juice, and clean your plate like Momma told you. About that, she was right!

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators