Most marinades are liquids that foods swim in before cooking. But marinades themselves are bathed in myth and mystery.

Table of contents

Marinades usually have a number of ingredients such as salt, oil, flavorings, and acidic liquids (SOFA). The molecules of each are different sizes and some are attracted to the chemicals in meats and some are repelled by them. Some can flow easily into the microscopic voids between muscle fibers, some are too large.

Marinade myths

Let’s debunk some myths about marinades, and then we can get into how to make them and how to make them work. Some facts:

Myth: Marinades penetrate deep into meat. Marinades are primarily a surface treatment, especially on thicker cuts. Only the salt penetrates deep. Period. End of story.

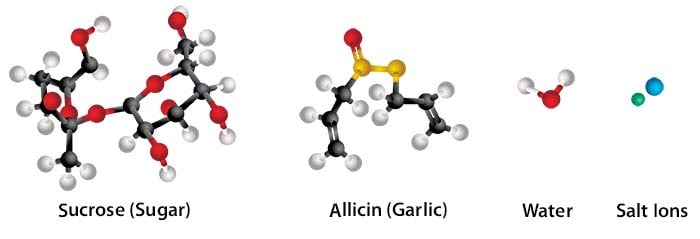

Salt penetrates because it reacts chemically and electrically with the water in the meat. But molecules like sugar and garlic are comparatively huge and they do not react electrically when dissolved. Salt is made of just two atoms, sodium and chloride, NaCl. Sucrose is C12H22O11, that’s 45 atoms. Garlic’s active ingredient is allicin, C6H10OS2, and it has 18 atoms, and garlic powder is even larger and more complex than that. Sugar can move inward a bit after days of marinating.

Marinades, unless they are heavy with salt, in which case they more properly are called brines, do not penetrate meats very far, rarely more than 1/8″, even after many hours of soaking. Especially in the cold fridge where molecules are sluggish. They can enter tiny pores and cracks in the surface but that’s about it.

Meat is a protein sponge saturated with liquid. About 75% of meat is water. There’s not much room for any more liquid in there. Think of a sponge. When you are wiping up a spill, as it gets fully loaded you just can’t get any more liquid in there.

As research by the AmazingRibs.com science advisor Prof. Greg Blonder has shown, it takes salt almost 24 hours to penetrate meat 1″ deep (see my article on brines).

On top of this, most marinades have a lot of oil in them. And meat is mostly water. As we all know, oil and water don’t mix. That oil is just not getting past the microscopic cracks and pores in the surface.

There are important exceptions: Fish, shellfish, eggplant, and mushrooms, for example, absorb marinades more rapidly and deeply (see the photos at right). But for most meats and veggies, the benefit of marinades is that they flavor the surface. We are often bamboozled into thinking the marinade has soaked in because the knife, fork, and liquid on the plate are full of marinade flavor, because the flavors on the surface get on our tongue, and they get pushed down into the meat by our teeth.

Try this experiment: Marinate a 2″ thick porkchop as long as you like in whatever you like. Since your marinade probably has some salt in it, take another 2″ chop and just salt it. Cook them side by side, bring them in and rinse them off to remove as much surface flavor as possible. Then cut off the outer 1/4″ of both. Be very very careful to not let the juices from the outsides touch the center. Now have a friend serve you tastes of both without telling you which is which. Hard to tell apart, aren’t they? They both taste like plain ol’ pork. You might taste salt, but no sugar, garlic, pepper, or whatever.

If you marinate thin slices of meat, say 1/2″ thick skirt steak, the flavors may penetrate 1/8″ on either side and so it will get close to the center, especially since skirt steak has loose fibers running parallel to the surface, but not thick pieces. Think of prime rib. The outside crust really tastes like the seasonings while the center tastes like plain old beef.

But in most cases it is good that marinades don’t penetrate very far. If that red wine marinade you used on your flank steak penetrated all the way, would you and your guests prefer purple meat to bright red?

But let’s not demean surface enhancement. When you cook meat that has marinated, the marinade cooks first before the meat. A touch of sugar can help with browning and add flavor and color. Spices and herbs on the surface can make wonderful aromas and moist surfaces attract smoke. And oil can conduct heat to the surface and help with browning and crust formation. Also, as you chew marinated foods, the flavors on the surface get mingled with the unmarinated portions creating the illusion that they have been flavored.

After you finish reading the rest of the marinade myths below, you will see some experiments that show how poorly marinades penetrate.

Myth: Marinades tenderize. Tenderizing is a process of making the proteins softer, both the proteins in the muscle fibers and in the connective tissues that sheath the fibers and connect them to bones (see my article on meat science). This softening is called denaturing. Since marinades do not penetrate very far they cannot denature the protein bonds much beyond the surface, so there is little tenderizing beyond the surface. In fact, some ingredients, especially acids, such as vinegar and fruit juice, can make some surfaces firmer, and some surfaces mushy. In some cases acid can even reduce water holding capacity. This can be good if you are trying to form a dry crust. Many marinades contain acids ranging from vinegar to wine to fruit juices to buttermilk to yogurt. They impact the surface but not much else.

Myth: Marinades improve everything. Water based marinades such as wine, beer, soft drinks, and juices keep the surface wet so when they go on the grill or in a pan, the water evaporates, steaming the meat, and steam can impede browning and crisping of the surface and prevent the formation of the crust or bark we love. Crisp brown meat has more flavor, and one of the main reasons we like to grill (see my article on the maillard reaction, caramelization, and why brown is beautiful). On the other hand, the wet surface can help prevent dehydration and the drying effect of the grill, producing moister meat.

Myth: You can use just about anything in a marinade. If marinades contain sugar, they can burn and ruin the food. Sugar is less of a problem for low slow roasting over indirect heat with convection airflow. And oils can drip off causing flareups and soot deposits on the food. You can use sugar and oil, but judiciously.

Myth: Longer is better. Actually, longer is worser. The problem is that acids in marinates mess up proteins, faux cooking them. That’s how ceviche is “cooked”. Fish is marinated in citrus until the proteins get all unwound and the color changes and they sorta cook. The longer meat sits in an acid, the mushier it becomes.

Myth: Stabbing with a fork helps marinades penetrate. Stabbing meat with a fork or a jaccard blade pushes bacteria down in. And the holes seal up as the meat collapses in on the trauma. A very tiny boit of marinade will fill the top of the hole, but it can’t go deep.

Myth: Vacuum marinators suck in the marinade. There are several companies that make devices in which you place the food and then a motor sucks out the air and creates a vacuum. In theory the vacuum sucks the marinade in. Let’s think about this. There is no air in meat to suck out. So all they suck out is meat juice which is mostly myowater. When you release the vacuum, a small amount of liquid will get sucked in just a fraction of an inch, but most molecules are just too large to penetrate. Keep in mind, marinating is primarily a chemical process not a physical process. The acids and salts have a chemical reaction with the food. And that is primarily on the surface. That said, on very thin cuts like jerky, the tumbling and sucking might help a bit. I have tested this on chicken breasts marinated for a wide range of times and the effect is minimal. Cutting into the meat shows no deep penetration. No real advantage over regular marinating.

This holds true for sous vide marination. Let me quote Anova, a premium producer of sous vide equipment “cooked meat doesn’t absorb marinades, and the outside of meats cook in roughly 5 to 10 minutes in sous vide, so you always want to marinate first before sous vide cooking — even if you leave the marinade in the bag. Flavor-boosting marinades without a lot of salt and citrus are fine to cook in due to their mild nature. Those with tenderizing or brining capabilities (and also alcohol) will be detrimental to the food, as it will cause over-marination.”

There is a small advantage to marinating in a vacuum sealed bag. You need less marinade.

Marinating at work

Below are cross sections of lean meat. They were all soaked for 18 hours in a simple marinade recipe: 3/4 cup of canola oil, 1/2 cup of distilled vinegar, 1 tablespoon of table salt, and 10 drops of green food coloring. Some of the coloring in these cross sections is caused by the knife traumatizing the muscle as it moved through. The food coloring has large molecules, but not as large as herbs, spices, and sugar, and it reacts differently with protein, but these models demonstrate how difficult it is for foreign objects to invade fortress meat.

Although not definitive, this study indicates that large flavor molecules as found in dyes and the herbs and spices in marinades do most of their work on the surface, within 1/16″ of the surface, or in cuts in the surface. It shows that salt penetration goes deeper, so marinades should always contain salt. Read more about this in my article on brines. The exception to the rule are lobster and it’s smaller cousin, shrimp.

This means that marinades are best on thin cuts of meat.

1) Beef sirloin. As you can see the dye significantly colored the surface, but it barely penetrated. There is a slight discoloration that extends an average of about 1/8″ caused primarily by the denaturing of the proteins by salt and acid. Where there were cracks and cuts in the meat, the dye got in deeper.

On some beef cuts, where the fibers are more loosely packed and run parallel to the surface, like skirt steak and sirloin flap, marinade will move in a bit further, and in the case of skirt steaks, which are rarely more than 1/2″ thick, a few hours of marinating can get it close to the center.

2) Pork chop from the loin. Again, most of the marinade is on the surface with a small amount penetrating a fraction of an inch, and salt going deepest to denature the proteins.

3) Chicken breast. You can see the marinade entered where there are cracks on the bottom, but not much got in anywhere else.

4) Pounded chicken breast. This breast has been pounded so it is at most about 3/4″ thick. I have photographed the place where two muscles meet, the tenderloin(left) and the pectoral (right). The connection is very thin and as you can see, although most of the marinade is on the surface, it has had an impact on the meat edge to edge. Also, the underside cracks when pounded, and marinade enters there.

5) Salmon steak. As with the others, slight penetration of large molecules, best in cracks. Some denaturing of proteins from the salt, oils, and vinegars.

6) Whitefish steak. No real dye penetration, but about 1/4″ denaturing from salt and vinegar.

7) Florida lobster tail. Lobster tail and shrimp are highly susceptible to marinade penetration. They really drink it up in a short time.

8) Yellow squash. Zero penetration through the skin, and unlike the meats, the dye doesn’t even discolor the skin. But unlike the meats, there is excellent penetration through the cut ends. If you marinate slices of squash, you can count on it going through.

Industrial marinades

You have probably noticed more and more meats in the grocery that are pre-marinated and “enhanced” which can include injection. A nice idea, more or less. It makes cooking dinner quick and easy, you don’t have to start the marinade the day before because the marinade has had days to work. The marinade has probably been formulated by a meat scientist and will not only tenderize and help retain moisture, but chances are it tastes pretty darn good.

On the down side, you may not want the additives and preservatives in your diet, and the meat might not be the freshest. So you are paying meat prices for water and additives.

According to the Amazingibs.com beef scientist, Dr. Antonio Mata, “The level of marination in retail branded products range from 8% to 22% by weight. Some cooked deli items contain up to 60% enhancement. There is a whole array of ‘functional’ ingredients that the industry uses to improve the retention of the marinade: phosphates, salt, starch, alginates, soy isolates, etc., etc., etc. USDA labeling regulations are not consistent. Any beef product that has been ‘enhanced’ must indicate on the label the level of enhancement but this does not apply to poultry products.”

Some better ideas

Injecting is much more effective in driving flavor down towards the center of the meat. Another excellent option is a spice rub. A blend of spices and herbs, it delivers more flavor per square inch than any marinade. And then there is a sauce. Pack in lots of flavor with a sauce which goes on just before serving. A great way to bring the brightness of herbs and the other usual flavors in marinades to the table with little effort is a board sauce. Or you can use all of these methods!

Gashing helps marinades work

Think of marinades as a spice mix. What marinades do best is find their way into cracks and crevices on the surface of meats producing a flavorful baked on spice blend, much like a dry rub. When it dries out during cooking, it leaves behind the flavors.

They work best on thick cuts of meat like roasts where the food bakes for a long time on the indirect side in a 2-zone system and the marinade can dry out, leave its flavor on the surface, and then brown.

In general, it is best to think of marinades as a spice blend. Where they differ from normal spice blends is that you can get exotic flavors that can’t normally find on your spice rack, such as flavors from liquids like wine, juices, coconut milk, soft drinks, liqueurs, etc.

Help marinades by gashing the food. Since marinades don’t penetrate very far into most foods, give them a hand. Gash your food. Cut slices into the surface, rough it up, give the marinade cuts, cracks, and pits to enter. There is also more surface area to brown and more surface area coated with baked on marinade.

This meat was gashed in a cross-hatch pattern with a knife before marinating. As you can see, the marinade has penetrated as deep as the gashes making 1/2″ cubes of flavored meat. This is a great technique for use with marinades.

Gashing even works on veggies like the yellow squash below.

Making a brinerade

A brinerade is a new word from the clever folks at Cooks Illustrated magazine to describe a marinade that has enough salt to do double duty as a brine, and in my humble opinion all marinades should be brinerades.

SAF

The best marinades usually contain three working components: Salt, acid, and flavoring, and if you remember the acronym SAF, you can create your own easily.

S is for Salt. Salt is the most important ingredient because it is a flavor enhancer and it is good at penetrating meat and altering proteins to hold more of its water during the trauma of cooking. Soy sauce is a great source of salt. Shoot for about 6% salt by weight. My article on wet brines will explain how to get there.

A is for Acid. Citrus marinades were probably among the first, historically. They have it all, acid, sugar, flavor, aromatics. Acid can denature protein on the surface and make the surface of the meat mushy so use them judiciously, no more than 1/8 of the blend, and only for their flavor.Typical acids are fruit juice (lemon juice, apple juice, white grape juice, pineapple juice, orange juice, and wine work well), vinegar (cider vinegar, distilled vinegar, sherry vinegar, balsamic vinegar, raspberry vinegar, or any old vinegar), buttermilk, yogurt, and even sugar free soft drinks.

Acidity is measured on the pH scale of 0 to 14. Solutions with a pH of 7 are said to be neutral. Below 7, the solution is acidic. Above 7 it is alkaline. Here are the approximate pH measurements some common solutions for reference. Obviously you do not want to use battery acid or lye. I include them for reference.

0 pH – Battery acid

1 – Stomach acid

2 – Distilled vinegar, lemon juice

3 – Carbonated drinks, orange juice

4 – Tomato juice, wine

5 – Black coffee, beer, yogurt

6 – Saliva, cow’s milk

7 – Pure water

8 – Sea water, wet brines

9 – Baking soda, olive oil

10 – Milk of magnesia

11 – Antacids

12 – Ammonia

13 – Chlorine bleach

14 – Lye, liquid drain cleaner

F is for Flavoring. Typical flavorings include herbs and spices such as oregano, thyme, cumin, paprika, garlic, onion powder, and even vegetables such as onion and jalapeños. It’s a good idea to add some umami. That’s the savory meaty flavor from glutamates found in meat stocks, soy sauce, and mushrooms. It is also a good idea to add some sugar. It aids in browning the surface, but go easy. Too much will burn the surface. You want it to caramelize after the water evaporates without burning.

Where’s the oil?

Most marinades contain oil, but oil cannot penetrate meat. Remember, meat is 75% water and oil and water don’t mix. Here’s proof that oil will not penetrate meat. In the image below, I dug a hole in a beef steak about thimble size and filled it with a nice greenish olive oil. I took the top picture 33 seconds after pouring in the oil. The bottom picture was after 3 hours, 9 minutes, and 58 seconds. As you can see, not a scintilla of oil penetrated.

Other tips

Refrigerate. Keep marinating meats in the fridge.

No alcohol. A lot of folks like to use wine, beer, and spirits in their marinades, but this is not be a good idea. Here’s what the great Chef Thomas Keller says in his award winning The French Laundry Cookbook: “If your marinating anything with alcohol, cook the alcohol off first. Alcohol doesn’t tenderize; cooking tenderizes. Alcohol in a marinade in effect cooks the exterior of the meat, preventing the meat from fully absorbing the flavors in the marinade. Raw alcohol itself doesn’t do anything good to meat. So put your wine or spirit in a pan, add your aromatics, cook off the alcohol, let it cool, and then pour it over your meat. This way you have the richness of the fruit of the wine or Cognac or whatever you’re using, but you don’t have the chemical reaction of ‘burning’ the meat with alcohol or it’s harsh raw flavor.”

Use a nonreactive container. The acids in a marinade can react with aluminum, copper, and cast iron, and give the food an off flavor. So do your soaking in plastic, stainless steel, or porcelain pans, or, best of all, zipper bags. Pour the marinade and meat in the bag and squeeze out all the air possible and the meat will be in contact on most surfaces. Put it in the fridge and flip it over frequently.

What to marinate. Thin cuts are best for marinating.

Now here’s a neat trick. Fresh pineapple, papaya, and ginger have enzymes that tenderize meat. Papain, the enzyme in papaya, is an enzyme in papaya and the main tenderizing ingredient in Adolph’s Meat Tenderizer. These enzymes work fast. Within 30 to 60 minutes the meat is ready for the grill. Alas, pineapple and papaya add very little flavor to the meat in such a short time. Some people like the softer meat, others feel it is mushy. You decide. The enzymes are destroyed by the canning and bottling process, so be sure to use fresh pineapple, papaya, and ginger if you want the tenderizing.

Go nekkid first. Chicken and turkey skin are very fatty and they are a like a condom to marinades. If soaked, they only get soggy and won’t crisp properly. So if the skin won’t get crispy, what’s the point? Get rid of it. Skinless chicken will drink up more flavor. And it’s healthier. And yes, you can get skinless meat crisp. If you must have the skin, cut it into 1/2″ squares and brown it in a pan over medium heat like bacon, and use it as a garnish. Read my article on chicken skin and duck cracklins.

Save money. Some recipes call for marinating in barbecue sauce. Don’t do it. It’s just a waste of expensive sauce because it is too thick to penetrate very far and most barbecue sauces are sweet. They can burn.

Warning. Remember, all uncooked meat has microbes and spores. If your marinade recipe calls for heating it, let it cool thoroughly before using it to discourage microbial growth. Used marinades are contaminated with raw meat juices so if you plan to use it as a sauce, it must be boiled for a few minutes. Better idea: Discard it.

A shortcut. If you don’t want to make a marinade from scratch, just buy a bottle of your favorite oil and vinegar salad dressing. The thinner the better. Salad dressings usually have all the necessary ingredients, although they tend to be too acidic, so diluting it 3:1 with water is a good idea. Just make sure you don’t get the Caesar. It has cheese and anchovies in it. We don’t need no cheese or no stinkin’ dead fish in our pork or steak. And watch out. Some salad dressings have a lot of gums (emulsifiers) and other additives that could burn or make the meat taste funny after they are heated so it is better to make something from scratch (see the recipe below).

Here’s my recommendation

Take my spice mix recipes and mix them with water to make a paste. Let it sit for a few hours so the water will extract flavors. While it is sitting, dry brine the meat with salt if the rub recipe does not already have salt in it. If it does, skip the dry brining. Then apply the paste to the meat and cook. Start indirect to bake in the spices, and finish direct to create a crust.

Some rules of thumb if you must marinate

Always marinate in the refrigerator and cover the meat so it doesn’t drip on other food. Never reuse marinades.

Smaller and thinner pieces marinate better since the small amount of penetration is a larger percent of the thickness, so consider cutting some meats into thin slices.

Turn the meat every few hours.

Marinate fish for 30 to 60 minutes at most, depending on the thickness.

Zipper or resealable bags are good for marinating and they need less liquid than bowls or Tupperware. When you are done, you can throw them away. No cleanup. If you use pots, use stainless steel, glass, or ceramic. Never marinate in aluminum, cast iron, or copper. They react with the acids and salts.

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators