You must read this before curing meats: We encourage experimenting on all recipes that don’t have preservatives added. Our curing recipes use Prague Powder #1 (PP#1) which contains small amounts of the preservative sodium nitrite. If you do it wrong you can make someone sick. So you should not experiment with the ratios of PP#1 or the quantity of liquids in a recipe. Our recipes are carefully calculated to be safe and were created with the help of food scientists. Please do them exactly as published and please read this page thoroughly before curing any meats so you know how to cure meats safely.

Some recipes you can scale up or down by multiplying the ingredients. Some, like ham, you cannot, you must use a special curing calculator we have created to tell you how much PP#1, liquid, and how long it will take. There is nothing like it anywhere.

You should not try to combine our curing recipes with others. This may shock you, but there is a lot of misinformation on the internet. Although we love answering reader questions, we cannot comment on curing recipes from other websites or books, or variations you want to try. Nor can we do the math for you if you need to use the calculator. If you are unsure what to do, then don’t do it. If you fail to follow our directions, please don’t ask how to fix your meat. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out. Sorry to be so pedantic, but we long ago decided it was a bad business practice to make our readers sick.

The importance of nitrites

Curing meat is a preservation process going way back to ancient civilizations long before refrigeration. Probably some primitive tribe discovered that a dead animal washed ashore hadn’t rotted, and although the meat was salty and gray, it was still tasty and nobody died when they ate it. Then they started experimenting, and along the way they killed a few kinfolk, but eventually they figured out how to preserve meat with salt.

Then, probably in the 1600s, somebody discovered that a mix of salt and saltpeter, when rubbed into meat, worked better. They didn’t know it, but the potassium nitrate in saltpeter kills Clostridium botulinum, the deadly bacterium that causes botulism. The nitrate also preserved the pink color of the meat.

Today hardly anybody uses saltpeter and neither should you. Specially prepared blends of salt with sodium nitrite and sodium nitrate are used by commercial producers. Called curing salts as a group, they are why bacon, hot dogs, hams, and corned beef are pink and why they have a distinctive tangy cured meat flavor.

Curing salts

Individually they are Prague Powder #1 (a.k.a. Insta Cure #1 or Pink curing salt #1), Prague powder #2 (a.k.a. Pink curing salt #2 and Insta Cure #2), Morton Tender Quick, and good old Saltpeter. All my recipes use only Prague Powder #1 which has only 6.25% sodium nitrite and no sodium nitrate. Prague Powder #2 has 4% sodium nitrate and it is used mostly on meats that are air dried and not cooked, meats that age because the nitrate slowly breaks down into nitrite over time so it remains active over months. But nitrates can also form nitrosamines, a compound that is a carcinogen in animals, although its effect on humans is still ill defined. Unless you are an expert, never substitute one curing salt for another, especially in my recipes. I describe them in detail in my article on the Science of Salt.

Nitrites, botulism, and safety

The idea that nitrites or nitrates were carcinogenic was the result of a flawed experiment in the 1970s and, although it has been debunked, the bad reputation won’t go away. In 2003 the World Health Organization flat out said it: “No association was found with oral, oesophageal, gastric, or testicular cancer.” Research shows that about 95% of the nitrites we consume come from the natural compounds in vegetables such as lettuce, spinach, celery, radishes, and carrots, and even some drinking water. There is even some in saliva. Click this link for more on the subject.

In moderate amounts the nitrite is processed by your gut and the bacteria in there. There is is converted to nitric oxide which is important to your body (not to be confused with nitrous oxide, aka laughing gas). Eating too much nitrite in a sitting can lead to methemoglobinemia which can lead to headaches, shortness of breath, nausea, rapid heart rate, fatigue and lethargy, confusion or stupor, and loss of consciousness. This condition occurs when nitrite in the blood deactivates hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen to muscles. It can also happen if you eat too much spinach, Popeye.

The AmazingRibs.com science advisor Prof. Greg Blonder explains that “Children and pets are much more sensitive to nitrites, and infants even more so. They lack certain enzymes and their digestive tracts harbor bacteria that convert nitrate in veggies into nitrite. This is why commercial baby food is designed to be low nitrite/nitrate, and why some parents who make their own natural baby food from spinach can actually harm a young child because spinach is high in nitrite.” For this reason you must store curing salts where children cannot get into them.

Clostridium botulinum

Clostridium botulinum is a curious and dangerous beast. It is the single most deadly food pathogen, far more deadly than pathogenic strains of E-coli or salmonella. Bot doesn’t grow well in the presence of air, so it forms tough shell-like spores and hibernates until conditions are right. The spores are commonly found in the environment all around you.

But they are not a problem unless conditions allow the spores to germinate and produce deadly botulinum toxin. Clostridium botulinum prefers anaerobic (oxygen free) conditions. So submerging meat in water for days is rolling out the welcome mat. And cooking the meat when it comes out is no guarantee of safety because the spores don’t start croaking til the temp hits 250°F or so. So boiling water won’t kill them since it never gets above 212°F, and most meats, because they are mostly water, can’t go much above 212°F.

As scary as all this sounds, the good news is that the Clostridium botulinum that emerge from spores are much more sensitive and they die at about 175°F and the toxins they produce are inactivated at about 160°F. You might ask, why not dry cure in air rather than in water? Because there is very little oxygen deep in the center of a slab of meat, so Clostridium botulinum spores can already hide and grow there. So it just doesn’t matter.

USDA and curing

It is widely believed that USDA has set the limit of 200 ppm for cured meats, but this is a myth. USDA has established regulatory limits for the addition of sodium nitrite at 120 ppm (0.012%) in wet cured bacon, 200 ppm (0.02%) for dry cured bacon, 156 ppm (0.0156%) for products such as frankfurters or cured sausages, 200 ppm (0.02%) in wet cured or injected products such as ham or pastrami, and up to 625 ppm (0.0625%) of sodium nitrite in dry-cured meat products such as country hams.

These are levels at the end of the cure. Dry cured meats may sit for months at room temperature exposed to microbes in the air and oxygen. Plus they are often consumed raw, like prosciutto, as opposed to cooked for bacon. Because nitrites decrease during curing, the residual levels, after a few days or weeks, are often 10x lower than at the end of the curing process. Our recipes target 125 ppm at the end of the process.

USDA also requires 550 ppm (0.055%) of sodium ascorbate or sodium erythorbate to be added in commercial bacon production. This increases nitric oxide formation and, as we explain in our article on the smoke ring, NO is what gives cured meats their pink color when it combines with the protein myoglobin. It also greatly reduces or prevents the formation of nitrosamines. Our recipes do not require these extra additives, so it is considered safe, even desirable, to use the 200 ppm as a maximum target. Prof. Blonder, has written about the subject of nitrite toxicity in detail here. I have written about nitrites and nitrates and the cancer scare of the 1970s here.

“No nitrite” curing

People often ask if they can cure meats without nitrites and just increase the salt. Salt inhibits bot’s growth, but won’t kill it. Neither will vinegar. You should not attempt to cure meat at home without a curing salt.

There are some “natural” or “no nitrite” cured meats on the market, but if you look closely at the label, they often have some sort of extract of celery in them because it contains nitrate which can convert to nitrite. There are recipes for “curing” that don’t use nitrites, so technically they are not really cures, and they cannot kill bot so they must never be submerged in wet cures. I consider them risky.

That’s why you must resist the temptation to improvise in a few key areas. But if you stick to my recipes, you can make absolutely mind-blowing pastrami, bacon, and more. I’ll discuss below where you can improvise.

Three common curing methods

In the days before refrigeration, cured meats were heavily salted, treated with saltpeter, smoked, and often hung in cool cellars. The salt, saltpeter, and smoke concentrations were inconsistent and the meats often dehydrated and grew molds as they hung. These methods have been perfected and the meats are highly prized.

The problem is that in order to do this properly you need a great deal of expertise and you should have precise thermometers, scales, measuring tools, and refrigeration, and you must maintain excellent sanitation. Don’t let anybody bamboozle you, even the most ancient tradition-bound old-world producers are government-inspected and use modern instruments to make sure they pass. The shop in Rome shown here is full of cool-looking artisanal cured moldy meats that have all been properly produced.

Today there are three common methods of curing meat: Injecting, dry curing, and wet curing.

Injecting

Injecting is for most inexpensive hams, corned beef, and bacon. The meat passes through a machine with scores of needles that stab it and inject a precise amount of curing solution. It is fast and cheap with little waste. But it tends to pump a lot of water into the meat diluting its flavor. You can do it at home, but it is tricky to get the right amount of salt and cure in there. One of the problems is that a single needle injector tends to create pockets of cure and pockets of no cure. And it doesn’t treat the surface with flavor. Tools and techniques for injecting here.

Injection curing should be left for the pros.

Dry curing

Dry curing is how they make prosciutto, Iberico ham, Serrano ham, and American Country ham. To dry cure, you mix up your salt and spice mix, coat the meat, and store it in a temperature and humidity-controlled space. Dry curing is slow. Simple bacon can take a week and large meats like hams can take months. Dry curing requires a lot of space to hold the meat and ties up inventory for far longer than most businesses like. The energy costs can also be burdensome. In dry curing, if you can’t control humidity, temp, or salt precisely, you invite bacteria and mold. Some are beneficial. Some are deadly. Before you undertake dry curing, you should be able to tell which is which. That means a good microscope and analytical tools. The long curing process often results in oxidized rancid fat, a funky flavor that, like funky cheese, some people love and some people hate.

Dry curing should be left for licensed pros.

Wet curing

Wet curing means submerging the meat in a chilled liquid with nitrites and/or nitrates and flavorings. The cure dissolves and disperses in the liquid and the liquid has a uniform concentration of cure throughout as long as you stir it occasionally. Because meat is about 70% water, the cure tries to achieve equilibrium with the liquid in the meat. Wet curing takes less time than dry curing, sometimes only days. On a commercial scale, it requires a lot of space and cooling.

If you are doing only a small amount at home, it is by far the best way to go.

The science of curing is pretty cool. Meat is really a protein and fat sponge that is about 70% water (see my article on meat science). Salt draws water out of the meat, concentrating its flavor and making it less hospitable to microbes. It also draws moisture out of bacteria, killing them. Salt also slows oxidation of the meat so the fat doesn’t go rancid quickly.

But salt also penetrates the meat. Salt (NaCl) is a very tiny molecule with only two atoms, sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). It easily splits into sodium and chlorine ions when wet. And they electrify and easily penetrate the pores and membranes.

Nitrite is also a small molecule, NO2, with three atoms, one nitrogen (N) and two oxygens (O). Nitrite breaks down into nitric oxide (NO) and binds to the iron atom (Fe) in myoglobin in the meat. Myoglobin is the protein that gives meat its red color. The chemical process is similar to the process that causes the pink smoke ring in smoked meats and it gives cured meat its characteristic pink color.

Why I recommend wet cures

I prefer wet cures because submerging the meat in liquid makes it easier to control the amount of salt in the meat. The salt concentration for wet curing is higher than the typical 4 to 6% brine used to moisten chicken, turkey, and pork before cooking. Nature seeks equilibrium, so it tries to make the salt concentration inside the meat the same as outside. So the trick is to create a cure that has the right amount of nitrite and liquid so that the nitrite will penetrate all the way to the center of the meat, preserve the meat, and fight off bacteria without allowing it to suck in too much salt or too much nitrite.

Wet curing prevents “hot spots” where there is more cure in one spot than in other spots, a problem in dry curing. Also, wet curing won’t make thin areas or meat saltier than thick areas of meat, a problem with dry curing. When submerged in a wet cure, the salt concentration is the same all around the surface and the laws of equilibrium keep the meat the same salinity throughout if you keep it in the cure long enough. In a wet cure, the humidity is easier to control than in a dry cure, it is always 100%. Wet cures also hide the meat from oxygen, inhibiting most bacteria and preventing rancidity. So making the process anaerobic protects you from all the bad guys except bot, and the nitrite knocks bot out. Another problem with dry cures is that you need to put it on a rack or hang it in the fridge so air can flow around it.

Curing times

Another benefit of wet cures is that you can leave the meat in the cure a bit longer than the prescribed time. The meat and the water will reach equilibrium and if you followed our recommendations for safe curing (like using distilled or boiled water), a rule of thumb is you can leave it in the cure for up to 25% longer than recommended.

In practice you may be able to go longer but we do not recommend it. The longer it is in the cure the greater the risk of contamination.

Wet curing vs dry brining

And yes, I know my endorsement of wet cures seems to contradict my love of dry brining other meats like steak, chicken, and pork. But with those meats, you are applying only plain salt, not curing salt, you are applying it a short time before cooking, and you are using salt in smaller quantities just to amplify the flavor. This is a vastly different chemical process.

All this said, there is one important argument in favor of dry curing. It encourages the growth of some bacteria and molds that, if you know exactly what you’re doing, can produce interesting flavors and complexity, especially in hams. That’s one reason why prosciutto is so expensive. In this picture you see an expert at Prosiuittificio Ghirardi Onesto in Parma, Italy. He uses a thin sharp bone and sticks it in every single ham that is aging in their temperature-controlled cellar, and then sniffs the bone to make sure everything is proceeding according to plan.

Why I recommend Prague Powder #1

All my recipes use Prague Powder #1, the most common curing salt. It is approximately 94% plain old salt with approximately 6% sodium nitrite, some anticaking agents, and a tiny bit of red dye. The red dye is not for the meat, it turns the salt pink so you don’t mistake it for regular salt or sugar in your pantry. It is not the same thing as Himalayan pink salt or Prague Powder #2. Prague Powder #2 and some other curing salts contain nitrates (with an a) which can form nitrosamines which can be carcinogenic under certain circumstances. It’s not easy to find Prague Powder #1 in groceries, but butcher shops, sporting goods stores where they sell sausage-making gear, and Amazon.com carry it. Just click the link. If you can’t get it, don’t substitute.

Why I recommend Morton Coarse Kosher Salt

Table salt contains some additives that we don’t need, so I recommend Morton coarse kosher salt because it is purer. But, as I explain in my article on salt (click the link), the grain size and the air spaces between the grains plays an important role in the salinity or the quantity of NaCl. A teaspoon of table salt contains almost twice as much NaCl as a teaspoon of Morton coarse kosher salt because it is smaller grain and tighter packed. Since salinity is a key part of these recipes, I have standardized on the most common kosher salt, Morton’s. Diamond Crystal and other brands have different salinity by volume and will not work in my recipes. Don’t tell me you can’t find Morton’s. It should be in every grocery store. If you insist on another salt you must alter the quantity. Use the conversions in my article on salt.

Why I recommend hot smoking

There are many recipes for cold-smoking meat. In them, you heat the meat very little and just flavor it with cold smoke. This is risky and I have written about the dangers at length in an article on cold smoking. All my recipes call for cooking the meat at temperatures of about 225°F to an internal temp of between 145 to 165°F. This pasteurizes the meat. Again, this is a safety step. Hot smoking is easy to do at home and makes great-tasting bacon, ham, corned beef, etc. They will keep for a week or two in the fridge and they freeze beautifully for a month or more.

Why I recommend distilled or boiled water

Tap water is almost always safe to drink, but it is never pure. It usually has small quantities of microbial and chemical contamination. Please use distilled or boiled water if the recipe calls for it. Distilled water is widely available in drug stores and many groceries. If you absolutely refuse to buy distilled water, then you can use other water but you must bring it to a hard boil for a few minutes and then let it cool thoroughly before the meat or nitrite go in. This will kill bacteria, but it can leave behind mineral contaminants that may make things taste funny.

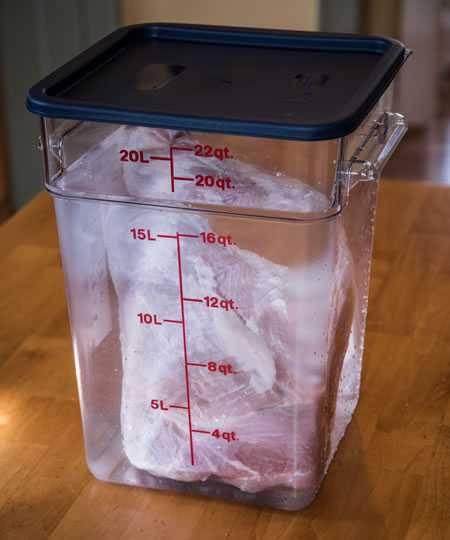

Cleanliness is crucial

You must make sure the container you will put the meat in will be super clean. It must be non-reactive meaning it must be food-grade plastic, glass, stainless, or porcelain. Aluminum, cast iron, brass, and copper pots can undergo a reaction with chemicals in food, especially acids and salts, and create off flavors.

Scrub it with hot water and soap, and then thoroughly rinse out the soap. Then mix one ounce of household bleach to a gallon of water and coat the interior of the container with that. Let it sit for 10 to 15 minutes or so. Then rinse thoroughly and dry with paper towels. The bleach will kill bacteria and the rinse and dry will remove any traces of bleach. Some people use Star San, a solution popular with brewers. Vinegar and alcohol are not as good as bleach.

You also need to scrub the meat with warm water. Normally we tell you that washing meat is not necessary and even risky because you can create invisible aerosols of bacteria in the washing process and the contaminants get all over the sink, faucet, dish drain, and counter surfaces. It is usually unnecessary because you are about to cook the meat and the high heat will pasteurize it immediately. But when you are curing meat, you are submerging it in water for days, so you want to get off as much of the flora on the surface as possible. You’ll never get it all, but get as much as you can.

Refrigeration is crucial

Most bacteria cannot grow at temps below 38°F, so it is crucial that you keep everything chilled below 38°F and above freezing of 32°F. Check your fridge temp with a good digital thermometer.

Curing math

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) says the maximum safe daily intake of sodium nitrite is about 0.1 milligram (mg) per kilogram (kg) of your body weight. That means about 7 mg of pure sodium nitrite for a 150-pound person. But we don’t (and shouldn’t) eat pure sodium nitrite. Instead, it is mixed into our cured meats. FDA regulations limit sodium nitrite (NaNO2) to less than 200 ppm (parts per million) in foods and hope a balanced diet will ensure the average daily intake is below the CDC regulations.

The fact is that there is some uncertainty about this number because scientists can’t give nitrites to people in large doses and wait to see what dose kills them or makes them sick. When we make cured meat we shoot for less than the 200 ppm number, but the fact is that nitrite is rapidly converted to nitric oxide (NO) during the cure so the actual amount is likely to be less. In addition, during the smoking process, a substantial amount can drip away as heat shrinks the meat.

Note from our science advisor

According to Prof. Greg Blonder, the AmazingRibs.com science advisor, while sodium nitrite is very dangerous ingested in its pure form, once absorbed by the meat it converts to nitric oxide and then bonds with the meat’s myoglobin. Very little remains active. To obtain a lethal dose, a 150-pound person would have to consume in one sitting about 175 pounds of cured meat containing 200 ppm sodium nitrite, more than his or her body weight! Even if you could eat that much, salt, not nitrite, probably would be the killer. Still, it is important, when you make your own cured meats, that you stay within safe limits because everyone’s tolerance is different, especially old, young, frail, or immune-compromised people. A few slices of cured meat on a sandwich every day, and a ham for Sunday dinner can’t hurt you.

In our cure recipes, we make sure you are well within safe limits. But remember, chemical reactions during the curing process and drip loss during cooking significantly reduce the dose. For more on the topic, here is an article by Prof. Blonder.

Why timing matters

It takes time for the cure to penetrate. If you get impatient you end up with meat that looks like this pastrami: Partially cured. Notice that the gray is exactly the shape of the slab. Special thanks to Pitmaster Club member “Smoking77” for sharing.

Some helpful numbers (rounded)

- Government regulations limit sodium nitrite (NaNO2) to less than 200 ppm (parts per million) in foods

- Prague Powder #1 contains 6% sodium nitrite (NaNO2) and 94% salt (NaCl)

- 1 tablespoon Prague Powder #1 weighs about 14 grams (depending on the spoon design) and contains about 0.8 gm sodium nitrite

- 1 gallon of water weights about 3,800 gms

- 1 tablespoon Prague Powder #1 mixed with 1.5 gallons water produces a cure of about 150 ppm (0.06 x 14 gm/1.5 * 3,800 gm)

Why shape matters

When using the curing calculator below you might wonder why we ask you about the shape of the meat and why the cure time is about half as long for a cylinder of meat compared to a flat slab the same thickness since the cure has to travel the same distance from the surface. Prof. Blonder explains this phenomenon in a detailed article on his website here. A short summary: Think of two football stadiums with four entrance gates, north, south, east, and west. If you open just the north and south gates on one (that’s the big flat brisket), and all four on the other (that’s the round loin), some people will get to their seats at the same time in both, but it will take longer to fill all the seats when only two gates are open.

Curing salts work their way to the center in a random fashion, diffusing willy-nilly into uncured spaces. There is no force that draws them in. In this video simulation, the frantic red dots represent salt ions randomly walking into both a rectangular slab of meat and a round cylinder. As you can see, like the stadium, the cylinder fills in faster.

Scaling recipes with Prof. Blonder’s Wet Curing Calculator

The recipes on this site are properly formulated and well-tested. Readers love them. As long as the thickness of the meat is within normal ranges scaling is just a matter of multiplying or dividing the ingredient quantities. This applies to my recipes for bacon, turkey legs, andouille, and corned beef/pastrami (as long as you separate the point muscle from the flat). But ham and Canadian Bacon are different because their thickness and weight can vary significantly. For them, you need a calculator to tell you how much PP#1 and liquid, and how long to cure. We have built in the calculator to the Canadian Bacon recipe and should have it built into the ham recipe soon. Meanwhile, to get the right amounts for them you must use Prof. Blonder’s Wet Curing Calculator, below.

It is essential that you remember, that all our recipes and that this calculator are for wet cures. You may see other recipes out there, but if they are for dry cures there is no comparison (read the rest of this page to understand the diff). Yes, I know there is another curing calculator out there on the interwebs but there is no author listed, the page has many broken links and graphics, the parent site appears to be abandoned, and it includes sugar which is not part of the cure, it is a flavoring. Please don’t ask us about the differences between that calculator and the one below written exclusively for this site by Prof. Blonder, an eminent physicist, engineer, and food scientist. This calculator is designed for home use. If you are considering doing this commercially, here is a document from USDA. Please do not ask us questions about large-scale or commercial curing.

Note:

Prof. Blonder has rounded some numbers to make the measurements easier to work with and because the volume of Prague Powder #1 can vary from brand to brand depending how the salt was ground. Prof. Blonder has also documented that measuring spoons can vary as much as 20% for dry measures (more for wet measures because the lips impact the meniscus). Humidity and how tightly you pack the measuring spoon are also factors.

That is why it is best if you use weights rather than volumes. But if you aim for 125 ppm and end up 2x higher or lower, it will still be safe to consume after cooking. Let us know how the calculator’s time estimate works for you (make sure to let us know all the conditions).

Prof. Blonder’s Wet Curing Calculator Version 4.0Before You Begin: Scale all ingredients except Prague Powder #1. For example, if the recipe is for 3 pounds and you are making 6 pounds, multiply all ingredients except Prague Powder #1 by 2. Once you complete all five inputs, this calculator will tell you how much Prague Powder #1 to use and how long to leave it in the liquid. Pay close attention your data entry so you don’t make a mistake. |

||

| Step 1 – Set Cure Level: Enter a cure level by moving the slider. We recommend 150 ppm of sodium nitrite but just about any number between 100 and 200 will work. 200 ppm is the maximum recommended by food safety experts, a conservative number, and you can go over a bit because there is drip loss during cooking, but you should play by the rules to be safe. | ||

| Step 2 – Enter Meat Weight: Enter the weight of the trimmed meat after you have removed all skin and surface fat. If you are curing brisket we strongly recommend you separate point from flat and remove the fat layer between them. Use decimal equivalents for fractions (enter 3.5 not 3 1/2).

Meat weight should be a positive value

|

||

| Step 3 – Enter Liquid Volume: Enter the amount of liquid in the original recipe times the amount you are multiplying the recipe by. If there are other liquids in addition to water such as maple syrup or sriracha, be sure to include them in your liquid totals. Note that our bacon recipes are designed to use less liquid than normal but don’t worry, they still work. Use decimal equivalents for fractions (3.5 not 3 1/2).

Liquid should be a positive value

|

||

|

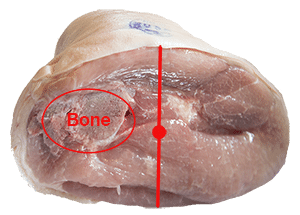

Step 4 – Determine Meat Thickness: Find the thickest part of the meat. Measure the shortest distance to the center. Multiply by 2.

Thickness should be a positive value

|

||

|

Step 5 – Select Meat Shape: Select the appropriate shape: Flat is like a pork belly, tube is like a pork loin, and cone is like a ham. |

||

Calculation Results{{ praguePowderGrams.toFixed(1) }} grams

{{ showPowderSpoons }}

Some fields in have invalid values. Please check the errors in red.

This calculation tells you how much Prague Powder #1 to use. Remember, it is not a multiple of the amount of meat. It is calculated based upon the variables you entered above. If you have a good scale, it is best to use the amount in grams rather than teaspoons or tablespoons. It is well documented that spoons from different manufacturers hold different amounts. If you pack the salt it will weigh 5% more than scooped. If you don’t level off the top of a spoon it can also make a difference. {{ cureTime }} days

Some fields in have invalid values. Please check the errors in red.

The calculation tells you how long to leave the meat in the cure. You can go 25% longer than the minimum time if you wish, but don’t push it any more. The longer it is in the cure the greater the chance of contamination. Don’t go shorter or you may have uncured meat in the center. |

||

| Copyright © 2016 - 2021 by AmazingRibs.com. Created by the AmazingRibs.com Science Advisor, Prof. Greg Blonder. Contact Meathead for permission to use it on your blog or website. This is version 4.0. |

Weirdness and troubleshooting

After a week in the cure, beef may look a little gray on the outside but stay pink in the center. That’s because oxygen has impacted the surface while the nitrites have fixed the myoglobin. Some fats may get gelatinous, particularly on ham. The water may get a little pink from myoglobin being pulled out, but it should never be cloudy. Bits of fat may break loose and float, but floating mold is a bad sign. Bubbles are a sure sign that something is alive in there and that’s bad. It should always smell fresh, perhaps a little briny, but never funky. When in doubt, throw it out!

Summary

Read my article on the Science of Salt.

My recipes use Morton coarse kosher salt, but if you must use another salt you must change the amount according to the conversion table in my article on salt. Beware, some salts have additives that can alter the taste.

Use only Prague Powder #1. Don’t substitute saltpeter, Tenderquick, Himalayan pink salt, or Prague powder #2.

Do not dry cure.

Do not stack slabs of meat. Be aware of thickness.

Do not use a batch of cure more than once.

Sanitation is crucial. Your containers must be rated “food safe”, clean, and non-reactive.

Use distilled water or boiled water.

Keep the meat submerged.

You must keep the meat between 34 and 38°F which is the ideal refrigerator temp.

Do not mix my recipes with others.

When in doubt, throw it out! Don’t take risks with meat. Even though you might cook it well past the safe temp of 165°F, botulism spores can survive to higher temps!

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators