Grill It In A Cast Iron Skillet (10 Recipes, 3 Pages, 2 Articles)

Published On: 2/26/2020 Last Modified: 9/24/2025

What’s old is new again

With all the conveniences of modern outdoor cookery like thermostats and remote controls via smart phone, why would anyone want to cook with something so primitive as cast iron?

Because it’s simple, and it works. Even though WiFi-enabled pellet cookers, sous vide machines, pressure cookers, slow cookers, multi-cookers, and Teflon pans and have made inroads into the cooking equipment we use on a daily basis, cast iron has never left. Pitmasters, home cooks, and professional chefs still rely on cast iron pans for essential daily cooking techniques like searing meats, frying, sautéing, simmering, braising, stewing, and baking. Other cookware can handle some of these tasks, but nothing delivers a dark, even sear on the surface of food like a cast-iron pan. The Iron Age is still with us (click here to share this bit of wisdom on Twitter). In fact, cast-iron cookware is enjoying a renaissance. Modern companies are meeting increasing demand for cast iron with a new breed of smoother, lighter, higher-quality pans that harken back to the vintage cast-iron pans of old.

How cast iron is made

Cast iron is pretty cheap and easy to manufacture. Cooks all over the world have relied on it for centuries. Archaeologists believe that the first iron was cast into agricultural tools and cookware back in the 5th century BC in China. Later, around the 15th century in England, iron was also cast into cannons and shot. Today, cast iron is still widely used around the world for everything from machine gear boxes to your car’s brake rotors (yep, that’s why your rotors rust).

Castings for cookware are made from gray iron, an iron-carbon alloy consisting of 97 to 98% iron, 2 to 4% carbon, 1 to 3% silicone, and sometimes other elements like phosphorus and manganese. The silicone helps prevent corrosion, and the carbon improves strength by forming graphite, a network of flakes. That graphite content is what gives gray iron its name and color. How does it become a cast-iron skillet? First a mold is made out of moistened sand that’s bonded together using clays, chemical binders, or polymerized oils such as motor oil. The gray iron is then melted in a furnace, poured into the negative cavity of the mold, and allowed to cool. When the sand mold is broken off, the iron casting is removed, the surface sandblasted or sometimes machined, and finally the pan is oiled or “seasoned.”

Like what you’re reading? Click here to get Smoke Signals, our free monthly email that tells you about new articles, recipes, product reviews, science, myth-busting, and more. Be Amazing!

Modern vs. vintage cast iron

Metal surfaces, no matter how smooth they look to the naked eye, are not really smooth. Under a microscope, you can see tiny imperfections, irregularities, and uneven surfaces. Many cast iron pans have a pebbly surface from the molds in which they are cast. Those bumps act as islands, tenaciously holding onto bits of cooked food, so early manufacturers of cast-iron cookware such as Griswold and Wagner machined away that roughness to make the cooking surface smooth. When heated with oils or melted fats, the fat builds up on the surface into a nice thick seasoning that can be nearly nonstick. That’s one reason why vintage cast-iron pans are highly sought after online and in garage sales: they’re smoother and tend to be less sticky.

But the extra step of milling cast-iron is time-consuming and expensive. Griswold and Wagner are no longer in business. The cast-iron manufacturers that survived, such as Lodge and Victoria, skipped that step to stay in business. Most cast-iron pans sold today are not milled, and these pans often need to be re-seasoned to keep food from sticking to the cooking surface.

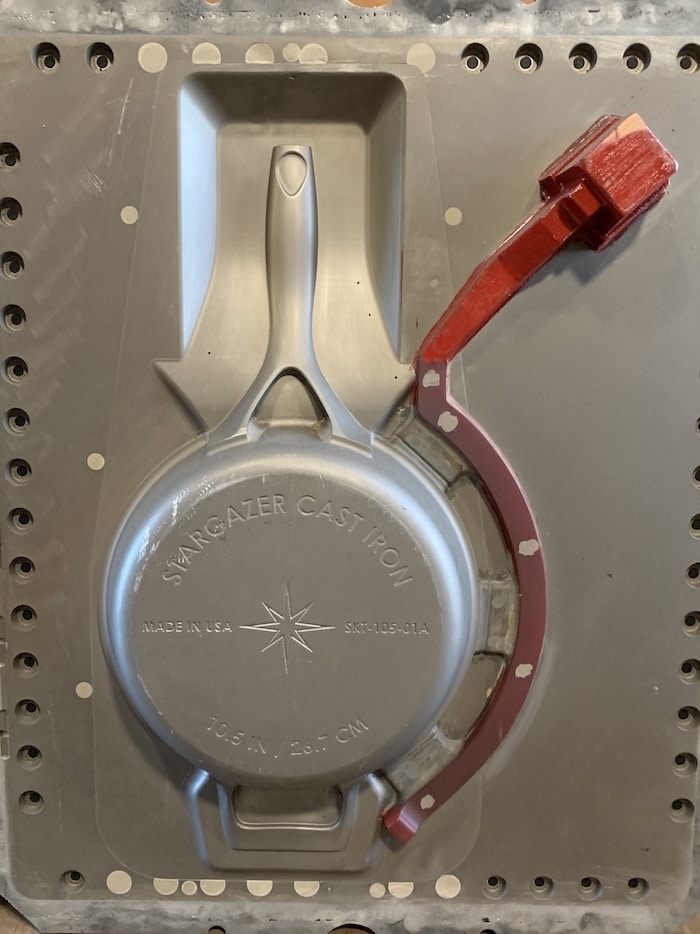

Fortunately, there’s a new breed of cast-iron manufacturers in town. Companies like Butter Pat, Field, FINEX, Lancaster, Smithey, and Stargazer have gone back to the old methods. They produce machined or milled cast-iron pans made of high-quality gray iron. Their pans are more expensive but perform more like the vintage Griswold and Wagner pans. And they’re not only smoother. Many of them are thinner, lighter, and stronger than your everyday cast-iron skillet.

MYTH: Cast iron heats evenly

BUSTED. People often cite the even heating of cast iron as one of its strengths. The truth: cast iron is only a fair heat conductor, about four times slower than aluminum. That means it takes a while for all areas of the pan to get hot, and it develops hotspots. When you put a cast-iron pan on a grill, campfire, or stovetop, it will be hotter near the hottest parts of the heat source but cooler further away from them. In the picture here, burn marks on the paper show where the heat is concentrated, matching the circular ring of fire from the stovetop burner. Eventually most of the pan gets hot enough to sear in, but if you want a cast-iron pan to heat evenly, the best method is to preheat it with consistent, even heat. An oven, pellet smoker, or grill set up for 2-zone cooking will surround a cast-iron pan with the most uniform heat. To help overcome the heat distribution shortcomings of cast iron, always preheat your pans before cooking in them.

What makes cast iron so good for cooking

You know those giant cauldrons hanging over campfires an old black and white photographs? Those pots were made of cast iron, and they lasted for decades because cast iron is nearly bombproof. Regardless of the machining process, cast iron cookware is hard to destroy, and it can withstand extremely high temperatures, like those in a raging wood fire. Even if you burn off the seasoning, you can resuscitate a cast-iron pot or pan by re-seasoning it. You can’t do that with Teflon. Once the Teflon coating goes, the pan is toast. Plus, burning Teflon is toxic.

Now, that doesn’t mean cast-iron is the one cookware to rule them all. In a perfect world, the ideal pot or pan would be made from a material that does everything well: it would heat up quickly, distribute the heat evenly, retain the heat well, and respond quickly to changes in temperature. Unfortunately, no such material exists. To harness the unique heating properties of each metal, today’s popular clad-metal pans fuse together multiple metals. They usually have a cooking surface of stainless steel because SS is durable, nonreactive, and easy to clean. But SS doesn’t conduct heat very well, so it’s sandwiched around an inner layer of either aluminum or copper, which are among the top three heat conductors on the planet (diamond is #1, and silver is up there too, but who can afford a solid silver skillet?). Clad-metal pans heat up fairly quickly and respond well to temperature changes. But because the pan’s material conducts heat so well and is less dense, it can’t retain the heat during searing.

Where clad-metal pans fall short, cast-iron excels. Heat retention and total heat capacity are among cast-iron’s most useful cooking properties. This type of metal holds and transmits enormous amounts of heat, which is why a cast-iron pan is unparalleled for producing a dark, flavorful sear on meat. The pan’s total heat capacity also means that when you add cold food to a hot cast-iron pan, the pan recovers heat quickly without a sharp drop in temperature. The downside of heat capacity and heat retention are that once a cast-iron pan heats up, it takes a while for it to cool down. Even the handles can remain blisteringly hot for quite some time after removing a cast-iron pan from the heat source. Solution: You can buy a sleeve for the handle, or use a mitt or folded up towel.

Part of what makes cast iron such a heat powerhouse is its high energy “emissivity.” Cast iron not only retains energy well but excels at radiating infrared energy. By contrast, stainless steel pans have low emissivity: food has to be in contact with a stainless pan for a significant amount of heat to be conducted to the food. But cast iron, especially when it’s dark and well-seasoned, emits more radiant energy, allowing food to be cooked indirectly, not just by conduction. Try this test: heat stainless steel and cast-iron pans side by side on your stovetop. Hold a hand above each and chances are (all other factors being equal) the cast-iron pan will feel hotter. The cast iron is radiating (emitting) more energy. That helps heat your food. The high emissivity of cast iron is particularly useful if, say, you want to cook the top of something like a pizza but you don’t have a broiler or another source of top heat. You can preheat a cast iron griddle or pan, suspend it over the pizza (perhaps on an oven rack), and the pan will radiate and cook the top of the pizza.

Want a new set of tools? Check out Meathead’s new book, The Meathead Method. It’s a toolbox that will elevate all your cooking. Alton Brown calls it “The only book on outdoor cookery you’ll ever need.”

What to cook in cast iron

Cast iron has a high melting point (2060-2200°F), making it excellent for campfire cooking and high-heat searing. Its superior heat retention also makes it a good choice for frying and long-cooked dishes like stews and braises. And it works on induction burners and can go from stovetop to oven. To help prevent the pans from rusting, some cast-iron is enameled, a type of glass that eliminates a few of cast-iron’s shortcomings: enamel covers up cast-iron’s reactivity, it jettisons the need for seasoning, and it makes the cooking surface smoother and easier to clean. The French companies Le Creuset and Staub only make enameled cast iron. The downsides? Enamel protects the iron from rusting, but it slows down the pan’s heat conductivity (and cast-iron is already on the low side). Plus, enamel can scorch, which means saying goodbye to that smooth nonstick surface. What’s worse, enameled surfaces can crack or chip with excessive force or sudden temperature changes, like when you deglaze a hot pan with cooler liquid. Bacteria can grow in any crack, so in many commercial kitchens, enameled iron cookware is prohibited.

We like enameled cast-iron Dutch ovens for stews, braises, and pot roasts because the food is acidic. But for most outdoor cooking, high-heat searing, and everyday stovetop tasks, we prefer “bare” cast-iron. It has a zillion uses. Cast-iron skillets are perfect for pan-roasting pork, searing steaks, shallow frying chicken and fish, baking cornbread, and even crushing peppercorns and pounding chicken breasts. Cast-iron Dutch ovens can be used for deep-frying, braising, stews, beans, chili, campfire cooking, desserts, and baking biscuits and bread. Cast-iron griddles easily handle burgers, fish, bacon, fried eggs, hash browns, pancakes, French toast…just about anything a short-order diner cook would make on a flattop.

The most basic and versatile cast-iron pan to keep on hand is a 10 or 12″ skillet. Use it to make our Red Eye Gravy with Ham. Or bake up some Killer Skillet Corn Bread. Make Seared Salmon on a Salad in a cast-iron pan. If you want some plant-based barbecue, try Barbecued Maitake Mushroom Steaks. There’s so much you can do. Whip up our Ratatouille cooked in cast iron on the grill. If you have a Dutch oven, make Fried Chicken on the Grill instead of stinking up the house with messy fry oil. Or sear a few Quarter Pounder Diner Burgers on a cast-iron griddle. A griddle is the second most useful cast-iron pan in your arsenal. That’s why we devote an entire section of the site to griddle grilling. In recent years, griddle grills and grill toppers have become wildly popular among backyard cooks. Check out that page for tons of cast-iron cooking tips, recipes, and reviews.

Yes, you have to maintain the seasoning, but that is simple. Click here for our complete guide to seasoning, cleaning, and repairing rusted cast iron. As far as we’re concerned, the only real downside to cast-iron cookware is its heavy weight. If that’s a problem for you, sleuth out and restore some vintage cast-iron or invest in one of the lighter, premium cast-iron pans from companies like Lancaster or Butter Pat. Then, to keep your cast-iron cookware purring like a kitten, think of it like a car engine: keep it well-oiled and use it often.

Cast Iron Vs. Carbon Steel Pans

The differences here are subtle but important. Cast iron contains 2 to 4% carbon while carbon steel contains only about 1% carbon. That difference in carbon gives carbon steel a more uniform grain structure, which strengthens the metal and makes it easier to form it into smooth, thin pans. That’s why carbon steel pans weigh less than cast-iron skillets.

Lighter weight and a smoother cooking surface are the most important differences between carbon steel and cast-iron pans. Otherwise, they perform very similarly. These two metals are both only fair heat conductors with poor heat distribution. That means both pans develop hot spots that match the heat source (eg. a circle of flame on a gas burner will create a circular hot spot on both pans). Both cast iron and carbon steel are prone to corrosion and reacting with acidic ingredients, making them less suited to long-simmered tomato sauces and wine reductions. On the plus side, both cast iron and carbon steel develop a nearly nonstick “seasoned” surface with repeated sautéing, frying, and cooking in oil. Both can go from stovetop to oven, and both pans work on induction burners. Most importantly, both pans excel at heat retention, making them excellent for searing steaks and crisping the skin on chicken or fish.

A few minor differences: carbon steel pans usually have sloped sides, while most cast iron pans have straight sides. That makes it easier to flip food and saute in a carbon steel pan. But the straight sides and depth of a cast-iron pan make it better suited to shallow frying chicken. Carbon steel pans also tend to cost a bit more than your basic cast-iron skillet, but maybe the lighter weight is worth it to you.

Bottom line? If you’re in the market for some new pans, a carbon steel pan and/or griddle is nice to have on hand for sautéing and searing. It’s lighter than cast iron, which is one reason why most restaurant chefs cook with more carbon steel than cast iron.

Make This Fried Chicken Recipe On The Grill And Skip The Mess!

Fried chicken is easy to do on the grill with no mess, no smell, and no smoke alarms. Give it a try with this recipe based on KFC chicken!

Elk Steak Seared In Cast Iron Is As Simple And Delicious As It Gets

YouTube BBQ star Malcom Reed joins us again with his super simple, super delicious recipe for elk steak. Click here for details.

The Ultimate Diner Burger Recipe (a.k.a. The Smash Burger)

Create the skinny, crispy edged burgers that you love at diners with this simple recipe for the Wimpy burger.

Griddled Salmon On A Salad Is Simply Simple And Delicious

Take ordinary salads over the top with this tested recipe for crispy crusty salmon. Fresh salmon is cooked on the grill with a griddle.

Fluffy Old Fashioned Skillet Cornbread

Skillet cornbread is a classic sidekick for BBQ with good reason and this is the perfect recipe for your next cookout.

Redeye Gravy With Ham, A Southern Classic

Ham and Redeye Gravy is a hearty Southern breakfast made in a cast iron pan designed to charge Mom and Dad for a hard day of work.

Ratatouille Tastes Better Grilled

Grilled ratatouille takes it up a notch. You may never make ratatouille the old way again! Serve it over pasta, couscous, or rice.

Paella Recipe: The National Dish Of Spain Began Outdoors And You Can Cook It Outdoors

A fabulously flavored rice dish, paella has many variations including this chicken and sausage paella recipe.

Barbecued Maitake Steaks Will Change the Way You Think About Mushrooms

Yes, you can smoke mushrooms on the grill the same way you smoke brisket. The key is a revolutionary new press-and-sear technique.Get Griddle Grilling With These Mouthwatering Recipes (20 Recipes)

Cooking on a hot griddle, flattop, or plancha is a great way to get a flavorful sear. Here are some great griddle recipes to get you started.

Mouthwatering Crab Cakes, Griddle Grilled To Perfection

Jumbo lump crab meat shines brightly in this recipe for griddle grilled crab cakes with rosemary aioli. Click here for details.The Definitive Guide to the Best Grill Grates (1 Article)

Which grill grate is best: stainless steel, cast iron, enamel coated, plated wire, or cast aluminum? The answer may surprise you.

How to Keep Food From Sticking to Your Grates

Don't you hate when food sticks to your grates? This article explains how to prevent it: keep your grates clean and use the right temperatureRelated articles

- Understanding Stainless Steel

- How To Season, Clean, and Repair Cast-Iron Cookware

- Frying Is Best Done On The Grill! (6 Recipes, 1 Article)

- Fried Chicken Recipe

- Elk Steak Recipe

- The Ultimate Diner Burger Recipe (a.k.a. The Smash Burger)

- Griddled Salmon On A Salad Is Simply Simple And Delicious

- Fluffy Old Fashioned Skillet Cornbread

- Redeye Gravy With Ham, A Southern Classic

- Ratatouille Tastes Better Grilled

- Barbecued Maitake Steaks Will Change the Way You Think About Mushrooms

- Get Griddle Grilling With These Mouthwatering Recipes (20 Recipes)

- Griddle Grilled Crab Cakes Recipe

- The Definitive Guide to the Best Grill Grates (1 Article)

- Paella Recipe: The National Dish Of Spain Began Outdoors And You Can Cook It Outdoors

- How to Keep Food From Sticking to Your Grates

- Irish Soda Bread On The Grill

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators